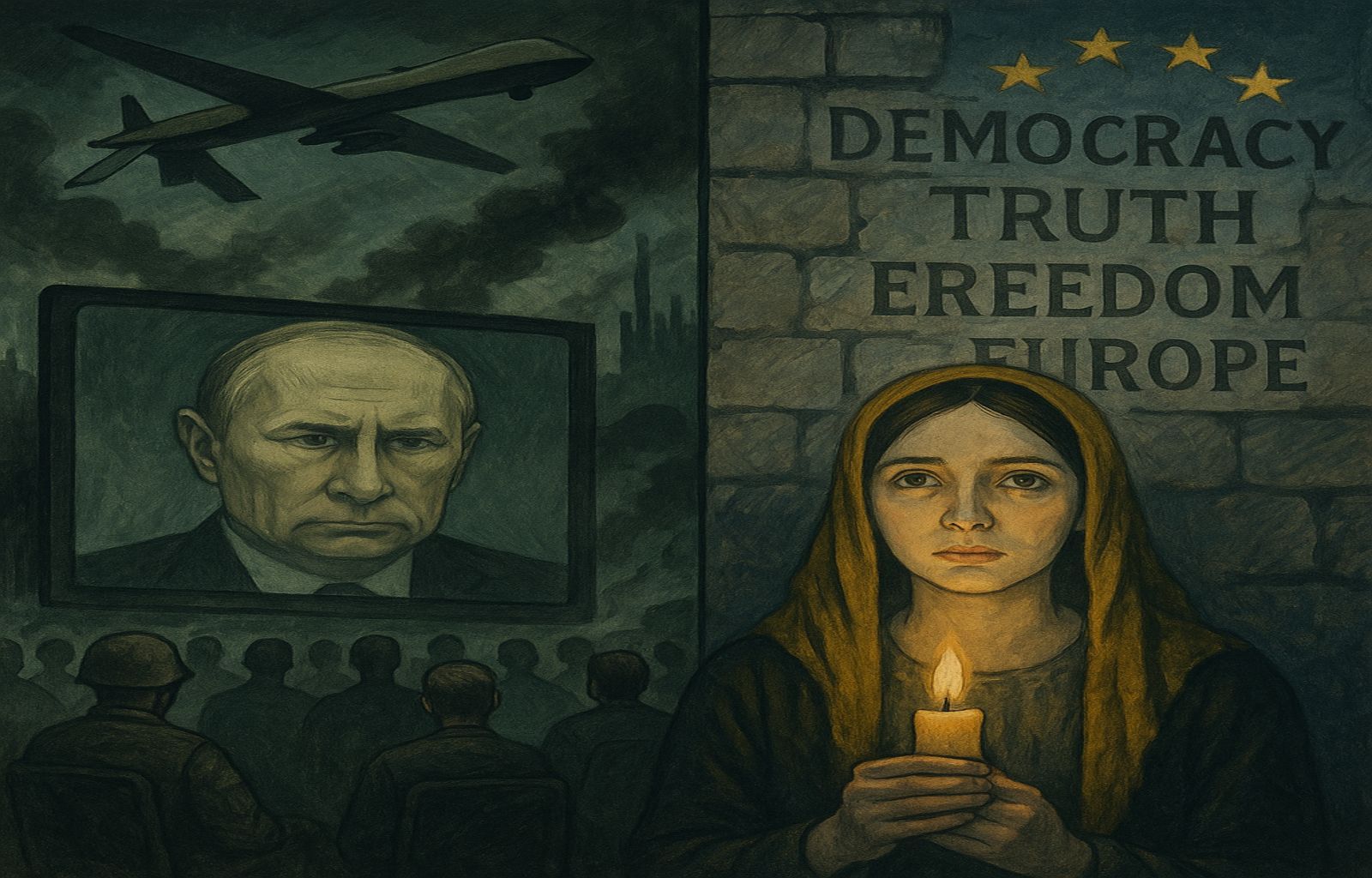

The myth of the failed Istanbul agreement: reality and propaganda

The recent meeting between the Moscow and Kyiv delegations on Turkish soil, organised to try to reach an agreement on a possible peace or at least a truce to the war that has been bloodyingUkraine for over three years, and resolved with nothing more than an exchange of prisoners, was an opportunity for our propagandists to dust off legends and lies about what happened in those very rooms of the Dolmabahce presidential palace in Istanbul in March and April 2022, when an attempt was made, in the first weeks of the invasion, to put an end to the ‘special operation’ desired by Putin.

There is hardly a talk show or news outlet these days that does not feature the know-it-all on duty, ready to assure that at the time a peace agreement was just a stone’s throw away and that it was British Prime Minister Boris Johnson who blew it with his surprise visit on 9 April, during which he persuaded Zelensky to continue the war rather than make peace. But we must be very clear in saying that this version of events not only finds no confirmation, but is in fact contradicted by the very sources cited by those who support it, as well as by the countless direct and indirect attempts at manipulation by the Kremlin.

Just a few evenings ago, repeating this narrative, which in recent years has literally depopulated Russian disinformation sites – and is still repeated in ribbons on social networks by supporters of Putin ‘s clique – were, on Otto e Mezzo, guests of Lilli Gruber, on La7, the director of Limes Lucio Caracciolo and the usual Marco Travaglio. Mieli’s objections, which he called that reconstruction ‘a lie’, were however countered by the director of the fact, re-proposing, as he has been doing for months, without any contradiction, alleged statements by the chief negotiator of the Ukrainian 2022 delegation, David Arakhamia, which in his opinion would corroborate this version of events.

Distortions on the Istanbul negotiation

According to the words also quoted in other television and editorial interventions, Travaglio refers to an interview given by the Ukrainian official to Ukrainian journalist and author Natalia Moseichuk, aired on 24 November 2023 on channel 1+1. Listening to it in its entirety, however, the suspicion arises that the editor-in-chief of Il Fatto never really listened to that interview, but rather relied on the manipulations that the Russian propaganda organs made of it, operating, as often happens, cuts and omissions.

About a third of the way through the long comparison, the talks in Istanbul are mentioned, about which Arakhamia states exactly the opposite of what Travaglio claims.

In particular, the official confirms that the central point of Moscow ‘s demands was non-membership in NATO, but he does not say at all that an agreement had been reached. In fact, on numerous occasions Travaglio speaks of 18 drafts that the delegations allegedly exchanged and a final one even signed. These statements had been made by Putin himself in front of a representation of some African leaders (partly confirmed also by the then Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett) to whom he had even told that document had been named ‘Agreement on Ukraine’s permanent neutrality and security guarantees’.

If Travaglio had actually listened to Arakhamia’s interview, he would know that that document simply does not exist, so much so that the interviewee points out to the journalist that if it had been real, Putin would not have hesitated to show it publicly, which he never did. What had happened in Istanbul was much more simply that the delegation did not have the power (nor the intention) to sign an agreement in violation of the Ukrainian constitution, which includes the goal of NATO membership, as of the changes made in 2019.

The interviewer, however, in the video presses Arakhamia, asking why they had not agreed to those conditions. And he explains what was all too obvious, namely that after eight years of annexations, clashes and provocations,Ukraine demanded guarantees for its security that Moscow was not willing to give.

To brand the untruthful nature of Travaglio ‘s reconstruction there is a direct question from the journalist on Johnson ‘s role and his alleged interference, to which the advisor clearly replies that these are untruths told by those who want to gain political advantage and that it wasUkraine‘s choice not to sign, because of the conditions imposed by Russia, as well as legal and constitutional constraints. Johnson did indeed visit Kyiv, but, as Arakhamia explains, that trip had taken place after the delegation had returned from Istanbul. For the sake of clarity, the same interviewee also specifies thatUkraine had not received any pressure from the Western partners, who moreover had access to the draft agreements, but, by Kyiv‘s choice, were not even aware of all the details of the talks.

Not very different is the manipulation that Travaglio picks up in full from pro-Russian propaganda sites, with respect to the statements of Oleksander Chalyi, a seasoned diplomat and member of the delegation led by Arakhamia, another proof, according to him, that the agreement was close and that it was blown because of the perfidious West. Here too, the doubt that the editor of Il Fatto does not know exactly what he is talking about is legitimate, not only because he repeatedly called that speech ‘an interview’, while it was a debate organised by the Centre for Security Policy in Geneva, but also because he failed to mention how Chalyi did not use enthusiastic terms at all when referring to those talks, but had rather pointed out that “Putin has committed a crime”, with reference already to the 2014 ‘proxy war’ and had specified in the second part of his speech, delivered in English, howUkraine ‘s membership in NATO and the obtaining of security guarantees remains the precondition for any agreement.

On the Istanbul talks, on the other hand, both the specialised journal Foreign Affairs and the New York Times had already written extensively, undeniably and in great detail. The former in particular, often mentioned without probably having been read thoroughly enough, contains a series of valuable details and references, which enable us to understand at least in part what really went wrong in the talks in Belarus and Turkey. The magazine essentially confirms that the main knot to be untied was that of security forUkraine and the security guarantees that in a post published on his Telegram channel on 14 March 2022, Zelensky himself emphasised that they were “not like those of Budapest”, with reference to the 1994 Memorandum with which Kyiv had agreed to divest itself of its entire nuclear arsenal, in exchange for assurances that Russia had, however, violated twenty years later, with the annexation of Crimea and the intervention of troops without insignia in Donbass. Guarantees on which the whole process had effectively ground to a halt, given Moscow ‘s niet with respect toUkraine ‘s entry into NATO and the Western allies’ reluctance to ensure direct intervention on the ground in the event of a new Russian invasion. Then there had been the discovery of mass graves in Bucha, Irpin and Borodyanka, which had somewhat hardened the Ukrainian position, and the substantial failure of the Russians’ attempt to seize the capital and the consequent withdrawal of troops to the east, which had allowed Kyiv to legitimately hope to sustain the war militarily. The authors of the article, Samuel Charap and Sergey Radchenko are, however, very clear in stating that the idea that the failure of the talks was due to Western pressure is in fact ‘unfounded’.

A myth without evidence

A decisive role, according to them, was played, if anything, by the insistence of the Russian side in wanting to include in the document drafted in early April – after a moment in which it had seemed that Moscow was even ready to agree to re-discuss the status of the Crimea occupied for eight years – a clause by which Russia, i.e. the invader, was given the right of veto that would allow it to legally prevent an international intervention in defence of the invaded country. A version, moreover, confirmed by the New York Times, which on 15 June 2024 published the incriminated document in full, dated 15 April 2022, the date on which the Ukrainian delegation, noting that the other side was not negotiating in good faith, had left the table.

In fact, therefore, all the elements lead one to believe that Johnson ‘s decisive intervention is nothing more than a myth to support which none of those who support that version of events are able to bring evidence, except for obscene manipulations that serial spreaders of fake news such as Caracciolo and Travaglio repropose at every opportunity. On the contrary, every testimony, reconstruction and document makes it quite clear that the rupture took place over issues such asUkraine ‘s right to have security guarantees (and consequently its sovereignty) which, not by chance, three years later, are still the elements that make the positions of the two sides in the conflict irreconcilable.

After all, Caracciolo, we should remember, on 15 February 2022 explained ‘why Putin will not attack Ukraine (whatever the US says)‘. Travaglio, a week later, i.e. less than 48 hours before the start of the biggest war of the century, on Social X, called the US intelligence warnings about the imminent invasion ‘fake news’. Of two such experts, who instead of burying themselves, continue to rage on TV as authoritative pundits, why should we not accept lessons in truth and geopolitics?