When death is cheap. The drone war and its consequences

In the early days of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, between February and March 2022, ordinary citizens spontaneously organised themselves to craft molotov cocktails to be thrown at the columns of tanks advancing towards urban centres.

It was like seeing images of Hungary back in 1956, catapulted in real time into our current affairs via Telegram and Twitter.

Three years later, the spontaneous mobilisation of Ukrainians continues, but to do something very different: to assemble or buy drones.

Videos on social media today show cellars and bunkers where drones are being built from makeshift materials, or fundraisers to send drones to the unit where a brother or schoolmate is enlisted.

They look like videos from the future, no longer from the past.

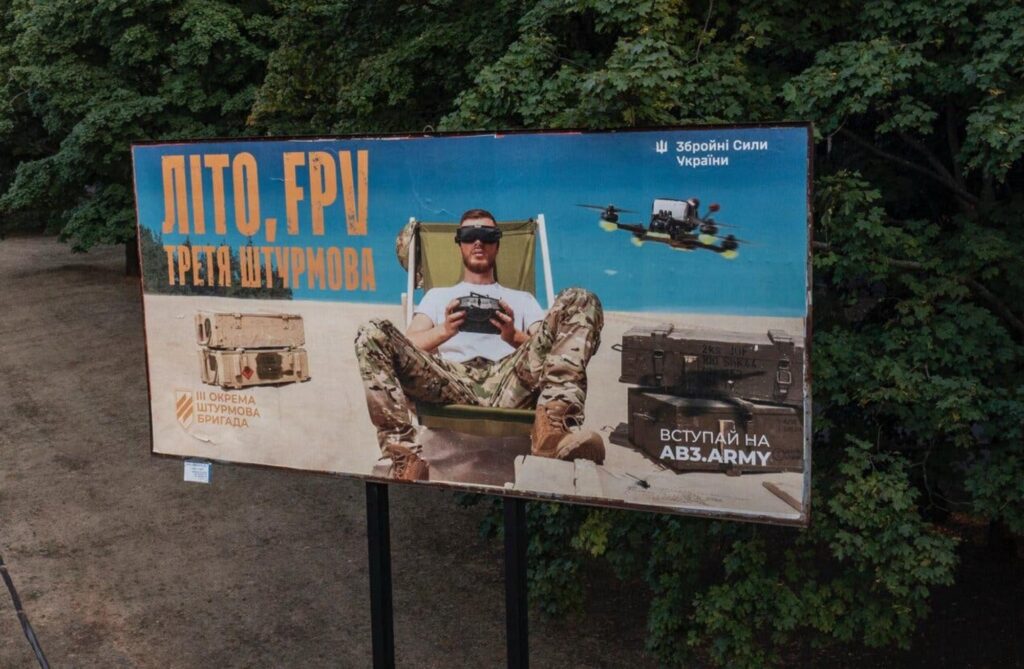

And the government’s and the military’s efforts to gain the upper hand in the drone war also seem to come from the future: underground factories assembling and lining up hundreds of thousands of drones a month, recruitment posters that make drone pilots look like relaxed soldiers far from danger, scouting among foreign video game champions to integrate them into their ranks, social media channels with footage of drones hitting weapons depots, refineries, ships and even helicopters and fighter jets, and frenzied investment in research and development.

On the other side, the Russian regime has built through three years an impressive production system for these equipments, improving on the patents of its Iranian and Chinese allies and importing thousands of young African girls as labour to be exploited in their factories.

A poster to recruit drone pilots.

Several times, during this race, Russia has found ways to outpace Ukraine by equipping its drones with features that challenged the latter’s defensive systems.

Flying at an altitude of more than 2,000 metres, for example, has made long-range drones more lethal, while fibre-optic cables instead of GPS have made short-range drones impossible to ‘confuse’.

Adding to the quality is the quantity: soon Putin’s hordes will be able to fire every night a thousand long-range drones at Ukrainian cities and ten thousand short-range drones at Ukrainian trenches and rear lines.

Kiev was also the first to cut a few corners, such as the use of Artificial Intelligence to make the drone capable of hitting the target even if it has lost contact with the base.

These are, however, competitive advantages that last a few months, sometimes only a few weeks. Then the rival power closes the gap and the advantage is cancelled.

But the overall effect of this race to innovate faster is, unfortunately, an increase in human losses on both sides.

Let us try to understand why, and what cynical strategic advantage the Kremlin is deriving from this situation.

Civil targets: those who defend are weakened compared to those who attack

Let us start with long-range drones. Between 3 and 4 metres long, loadable with up to 90 kg of explosive payload and cheap (they cost no more than 30,000 euros), they are flown by the Russians in swarms against cities inhabited by defenceless civilians.

To protect their lives, the defenders are forced to waste the rare interceptors of the Patriot, SAMP-T, or IRIS-T anti-aircraft systems, to deplete portable MANPAD anti-aircraft rockets, or even to scramble fighter jets.

It is mainly in this way that the Ukrainians are using the fleet of some forty Western fighter jets, F-16s and Mirages, transferred to them from France, the Netherlands and Denmark. And it is in this type of mission that two Ukrainian pilots have already lost their lives, while a third miraculously survived.

In short: when it comes to civilian targets, drones weaken the defender compared to the attacker.

Even when the assault is repulsed (and so far Ukrainian anti-aircraft fire has been 95% effective in shooting down Iranian Shahed and Russian Gerans), it consumes precious ammunition: in the long run, Ukraine will have to ration it, choosing which civilian buildings to abandon to destruction and which to preserve.

Add to this the fact that, at least once a month, the Shahed and Geran swarms do not arrive alone, but accompanied by ballistic missiles (such as the Iskander or Kh-101) that overloaded anti-aircraft defences struggle to intercept.

In the last attack on 25 May alone, 69 were fired, killing thirteen civilians, including Roman Martyniuk, aged 17, and his little brothers Tamara and Stanislav, aged 12 and 8.

Finally, let’s consider that mixed in among the real drones are some fake ones, i.e. without explosives, which are almost impossible to recognise by radar, and force one to waste additional anti-aircraft ammunition.

Photos of the Martyniuk brothers from the archive of Korostyshiv High School No. 1

Thus, those who live in large urban centres now receive nightly notifications from neighbourhood Telegram channels warning of incoming missiles and drones.

Sometimes they last for three or four hours. Most families have given up going down to the apartment block bunker each time and just move to the bathroom or at least to the room furthest from the outer walls of the building. Between the security of not dying and the freedom to live a normal life, everyone seeks the balance that seems most tolerable to their conscience.

Even the nightlife in the clubs, which in recent years has tried to go on though adapting to the midnight curfew, is punctuated by the programmed blackouts that are triggered by the arrival of Russian drones, often directed against the power grid.

There is, however, one capital city that is completely unrecognisable and reduced to a phantom existence: Kherson.

Close to the mouth of the Dnieper, it was liberated in November 2022 after six months of harsh occupation. Unfortunately, however, due to informal agreements between Washington and Moscow, the front line could not be moved further back than the river, so that today it is very easy for the Russians to release swarms of small drones against the inhabitants of the city, chasing them through the streets in human safaris of which they then boast online.

Italian engineer and reporter Giorgio Provinciali documented a few days ago that the same sadistic practice is also beginning in the northern capital of Sumy , whom residents are launching fundraisers to install antennas on the roofs of their cars to jam the drones’ signals.

As for rural villages, several have collected drone debris for their civic museums and municipal halls, knowing that it now forms an indelible chapter of their history.

A downed Shahed used by Ukrainian soldiers as a Christmas tree. From the ‘Saint Javelin’ page

While Ukraine is running for cover (putting into service, for example, the Sky Sentinel automatic cannon that has already successfully eliminated five drones), it is returning the blow. Not against houses and hospitals, but against those same industrial districts that manufacture the enemy missiles and drones.

Moreover, for the past few weeks Ukrainian drones have been managing to hover around Moscow airports almost every day, forcing them to suspend or postpone flights: a multimillion-dollar loss for Russian airlines, which are already struggling with breakdowns and shortages of spare parts due to sanctions.

(In Ukraine, by the way, civilian planes have been grounded for three years).

There are those who accuse these flights over Moscow of being pure media gimmicks – in Italy we would say ‘à la D’Annunzio‘ – that waste important resources just to boost domestic morale and give the impression abroad that Ukraine is winning.

In part, these are well-founded accusations, but we must not forget how large a volume of drones the Ukrainian industry is able to produce every month. Sending a dozen a day to pester Moscow’s airports might be less of a sacrifice than one would think.

Military targets: the attacker is weakened compared to the defender

But the bloodiest revolution is the one caused by short-range drones directly on the battlefield.

From simple ‘winged cameras’ to do reconnaissance and address artillery shots, these have turned into real smart projectiles, capable of penetrating enemy positions up to a depth of 40 km.

Throughout 2023 and 2024, the Ukrainians and (with less luck) the Russians had dealt with this threat by confusing the signal with which the drones flew, as well as by reinforcing the armour of the vehicles.

The Russian ‘blyatbarns’ had caused web hilarity, but less than a year later the Ukrainians had been forced to imitate them.

Now the year 2025 has seen the mass arrival of fibre-optic drones, impossible to ‘confuse’ and so small and precise that they can fit inside a truck or armoured vehicle.

The mobility war, therefore, is over for now.

The two armies are scattered in small units like platoons or companies, barricaded in trenches, basements or farms, and forced to shut doors and windows to prevent the drones from entering by surprise.

It sounds like an apocalyptic movie, but it is reality for more than half a million soldiers engaged on the contact line.

A 40 km radius also means the collapse of any logistics.

Until earlier this year, it was the Russians who had to transport crates of food and ammunition in civilian cars and then even on foot, for fear of drones crashing into their trucks.

The offensive launched in the spring of 2024, towards Toretsk, Pokrovsk and Chasiv Yar, had stalled because of this.

Again, the web had laughed at their failures.

But as soon as Putin’s generals, with the help of the Chinese, were able to deploy fibre-optic drones in sufficient numbers, the Ukrainians also found themselves in the same unmanageable situation.

The first Russian brigade specialised in drones, the Rubicon, was decisive in making the Ukrainians retreat from the Kursk region, compromising their logistics while the North Koreans’ human waves attacked them regardless of the high casualties.

Now there is a serious risk that the same tactics (flocks of fibre-optic drones followed by suicide assaults) will result in the fall of Toretsk, Pokrovsk and Chasiv Yar by the end of this year.

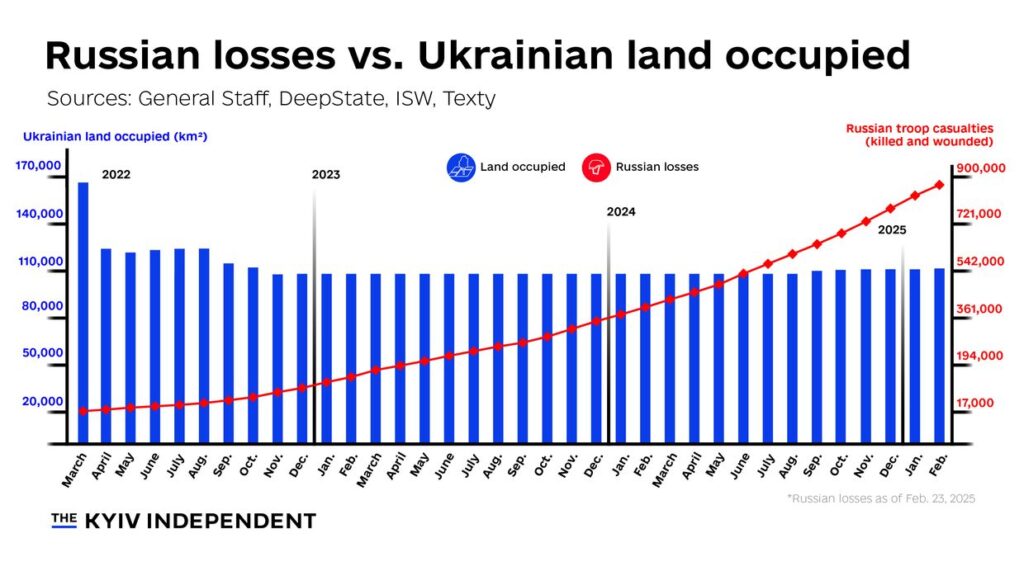

Beware, however: if in 2022 losing a ‘strategic railway junction’ like Pokrovsk would have been a danger to the entire Donetsk region, today it would only have the effect of moving the gruelling drone manhunt some twenty kilometres further ahead. This at the frightening price of 1,200 dead and wounded a day among the attackers alone (as well as 400 million a day preyed upon elsewhere in their economy).

In short: when it comes to direct confrontation between the two armies, drones weaken the attacker compared to the defender.

This means that the despot in Moscow can forget about conquering the whole of Ukraine, or even the entire so-called Donbass.

But it also means that Kiev will not be able to win back on the ground the 18% of its territory that is still under occupation.

This is a war of attrition, which will only end with the internal collapse of one of the two contenders, and which unfortunately, because of the drones, wears down precisely where Ukraine is most vulnerable: in the high rate of human casualties.

Human lives, in fact, as we know, are the asset that the Russian dictatorial regime can endlessly sacrifice without consequences, while Ukraine, which is a democratic nation, more European-minded, but above all smaller and with 1/6 of its population refugees abroad, must be careful to protect them as much as possible.

Therefore, the cheaper it becomes to spill the blood of a civilian or a soldier, the more the Kremlin considers itself favoured and continues with its aggression.

That this has been Putin’s cynical strategy since the summer of 2022 is a certainty.

That this, in the near future, could become the modus operandi of any totalitarian regime at war with a democracy, for now is only a fear.

An Israeli military-focused journal published a study a few days ago on the use of drones in Ukraine, arguing that the Jewish state must equip itself well in advance if it does not want to fall victim to this kind of conflict.

Of course, to dissuade the regimes of today and tomorrow from pursuing this strategy there is only one way: make Russia lose this war and show that it wasn’t worth it.

And to make Russia lose this war there is only one way: shift the attrition to the assets where she is most vulnerable, first and foremost the oil trade.