Are Ukrainian young men really being kidnapped in the streets by patrols?

In recent months, videos have gone viral on the web of men in military uniforms forcibly seizing Ukrainian civilians, seizing them during a concert or on a dog walk. Other videos showed women protesting against the forced conscription of their family members.

On the social media controlled by the Kremlin or its allies, such as Telegram and Tiktok, these videos have garnered tens of millions of views, fuelling an entire propaganda legend: Ukraine is so desperate and short of soldiers that it has to treacherously kidnap new recruits. Moreover, by doing so, it shows itself to be more ruthless than Russia, where most fighters enlist by choice. “So much for democracy versus dictatorship”.

But what are the facts behind this legend?

A limited phenomenon

In colloquial language, the Ukrainians have invented the word ‘busification’ to describe what recruiter patrols sometimes do: they stop men of draft age in the street on the pretext of checking their exemption documents from military service (nothing strange so far), but then, if the unfortunate man does not have his documents with him, they take the opportunity, immediately load him onto a bus and send him to the training camp.

The ‘busification’ episodes filmed and spread on social media were less than a dozen, filmed from different angles to pretend there were more. But they were enough to exasperate Ukrainians, who associate these practices with a Soviet past they no longer want to relive.

Apart from the blatant cases of ‘busification’, last year the Ombudsman received around 4,000 complaints against abuses by recruitment officers. This may seem like a high number, but proportionally it concerns just 1% of soldiers enlisted in 2024 and 0.4% of soldiers enlisted from 2022.

Of course, one may think that thousands of new recruits were afraid to report the abuses they had suffered, and therefore preferred to remain silent. But the army officers themselves encourage speaking out, and are critical of their colleagues in the enlistment centres: they know that a soldier forcibly taken and abused is more likely to desert or even retaliate by passing information to the enemy in times of danger.

They are therefore the first ones who do not want men sent to the front by brutal methods.

The reaction of politics: between common sense and populism

The Verkhovna Rada, i.e. the lower house of parliament, had to react to this pressure from the army, as well as to the wave of popular indignation that rose after the release of the videos, especially in the small rural centres far from the front, where news about the conflict (absurd as it may seem) comes more from Tiktok than from first-hand sources.

Thus, on 12 March, a law was passed increasing the penalties for those who recruit a man illegally to up to eight years in prison . Since June, the Rada has also decided to appoint an Ombudsman only for the military.

The debate was not without populist excesses. There have been MPs who, in order to exploit popular anger, have proposed that the staff of the hated enlistment centres should wear a recognisable uniform different from that of the army, which instead (for obvious reasons) is much loved.

Half-mouthed, some retorted that if the people-hated categories were to wear special uniforms, politicians should be the first…

However, the Rada did not only think about punishing those who play ‘strong with the weak’, but also those who play ‘weak with the strong’, i.e. those conscription centres and military medical commissions that spared several citizens conscription in exchange for hidden rewards.

That is a form of corruption that once again reminds of Russia and the Soviet mentality.

How many Muscovites and Petersburgers have gone into the trenches in recent years? 0.3% of those of draft age, despite the great mobilisation of 2022 and three other annual mobilisations.

In fact, the famous enlistment queues, which are filling Putin’s battalions with more than 30,000 fighters a month, are queues of poor people from peripherical regions, such as the Caucasus or Siberia, where the enlistment bonus of around $25.000 is equivalent to four or five years’ salary.

Fake marriage agencies for ‘black widows’, i.e. Russian women willing to marry a man who is going to die in Ukraine in order to pocket the fabulous compensation of $95.000, have also made headlines.

In short, for the Russians, it is normal for war to be waged only by those who have no money and no connections. And the Ukrainians do not accept that it becomes normal for them too.

The point of view of the centers’ employees

The clampdown on Military Medical Commissions was not the first intervention of the Ukrainian Rada on the criteria for exemption from military conscription. In the first months of the total invasion, it was enough to prove that one had a relative with a disability in order to be spared: therefore, as was predictable and perhaps inevitable, the hunt was on for great-uncles and third cousins, until after some time the authorities backtracked by restricting the perimeter to close family members.

Knowing these continuous difficulties, some people in Ukrainian society put in a good word for enlistment centres’ employees.

After all, summoning and sending more than a million people to the right units was a considerable logistical effort. Moreover, it was not only those who currently wear the uniform who passed through those centres, but also all other male citizens between the ages of 25 and 60, who had to give their details, address and telephone number to potentially be called up. If we exclude those who fled abroad in the first months of the total invasion, that is almost 9 million men.

Well, those defending the officers of the centres claim that it was not men exempt from conscription who were forcibly taken, but simply men who had avoided turning up to give their addresses and contact details. Therefore, on paper, draft dodgers and outlaws.

Let’s add that to run such a complex structure, at a time when young officers were desperately needed on the front line, the Ukrainian government had to call into service old, retired officers: men born and bred under the Soviet Union, trained on Soviet military manuals, accustomed to the Soviet hierarchy and insensitive to Western freedoms.

These have been gradually joined by thousands of wounded and maimed who, having returned from the front line, are continuing their service at the desk.

Now, one can sense that both of these human groups do not have a flattering opinion of those citizens who ‘played smart’ and did not show up at the enlistment centre to give their contact details.

And, if it were the latter who were ‘busified’, the Law could do little to help them.

The unpredictable feelings of a European people at war

So, for a part of Ukrainian society, these episodes, even if not justified, are at least understandable.

Just as, on the other hand, desertion is considered understandable even if not justified: the 132,000 deserters listed at the beginning of the year were calmly invited by the government to return to their units without any punishment, and 30% of them have already done so.

This fluidity may seem strange to those who imagine every war as World War I, with draft dodgers hiding in the woods, decimations, executions and all that our great-grandparents used to tell.

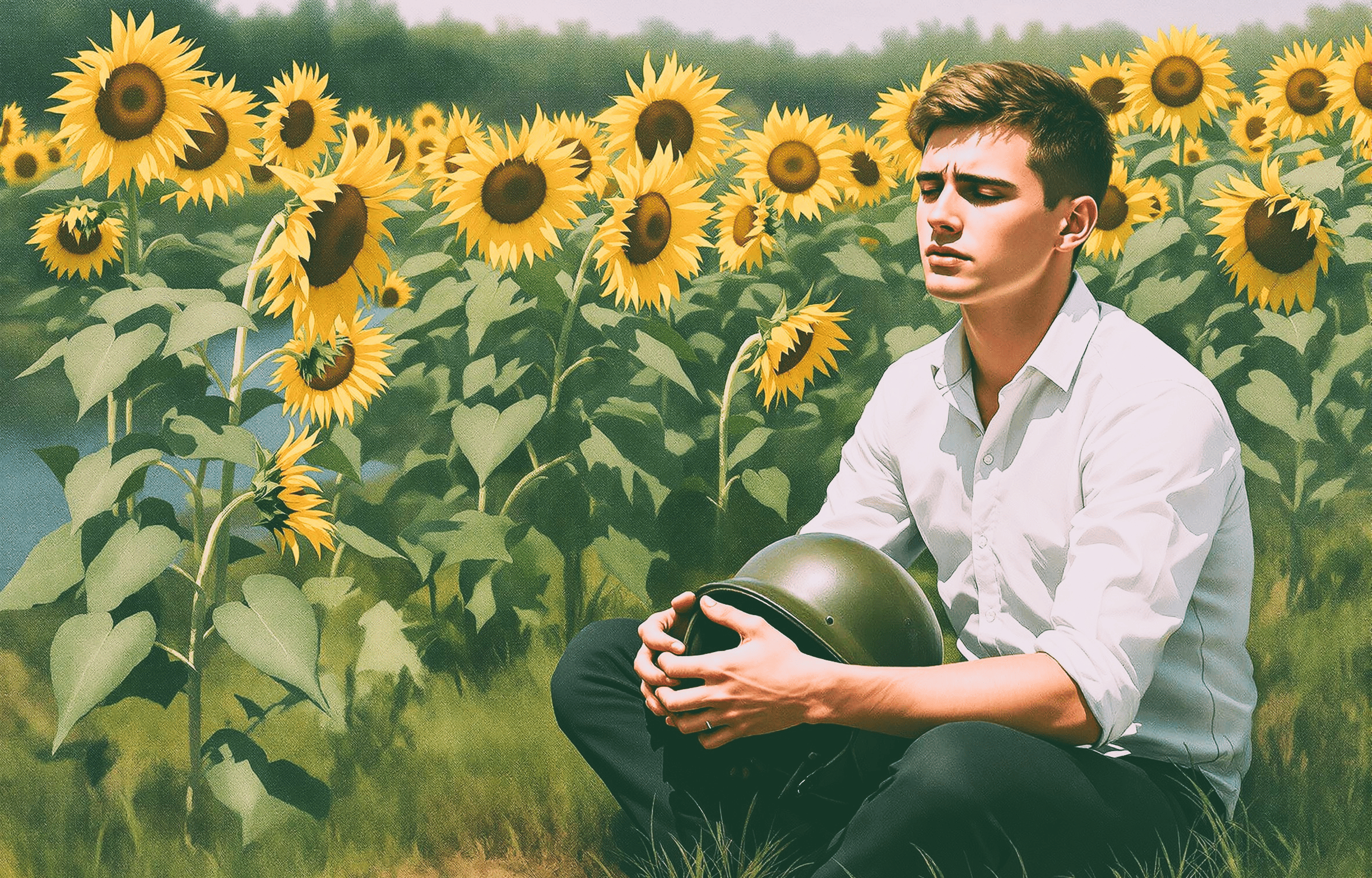

But Ukrainians, we repeat, have a European sensibility and modern ways of life. They do not demonise feelings such as fear or the desire to remain close to their loved ones.

Our great-grandparents who fought World War I, for example, would have found absurd an army with an average age of 45 like the Ukrainian one, where mature men go to war to keep boys’ lives safe.

But to modern European sensibilities this is normal and, indeed, the opposite would be inhuman. (By the way: in the Russian army the average age is 35).

Let’s not forget, furthermore, that Ukrainians have constant access to information about what’s going on in the world and follow in real time the election paranoia of their Western allies, on which their equipment, their intelligence and their greater or lesser risk of dying depend.

A Ukrainian friend told me frankly: ‘We all want to defend our homeland, but we are not all willing to defend it with our bare hands’.

In short: when Ukrainian society feels abandoned by the West, it becomes more tolerant towards the deserters, but in some cases it also becomes tolerant towards the recruiters, who have to do their work in a climate of collective despondency.

When, on the other hand, one succeeds in cornering Russia, as during the Kursk raid or Operation Spiderweb, hope is raised and enlisting new men becomes easier.

The influx of soldiers for physical warfare depends on media warfare, and this is why people like President Zelensky or intelligence chief Budanov periodically organise ‘psychological’ or ‘political’ operations of dubious war value, which attract the scorn of military experts and analysts across the West.

If war were a game of chess or Risk, those experts and analysts would be right as rain.

But war is the mobilisation of a people who are pushed to risk their lives. And, when it comes to a third-millennium European people, mobilisation has to come to terms with the innate sense of their own dignity, the expectation of a long life , and the distrust of hierarchy that characterise any third-millennium European.

Ukrainians do not allow themselves to be moved around like pawns or tokens. And that is one more reason, not one less, to be on their side.