The pathologisation of power: performative diplomacy, force and the illusion of madness

In the contemporary narrative, especially in the media, it has become almost a conditioned reflex to ‘explain’ the decisions of authoritarian or unconventional leaders through the prism of mental pathology. Failure to understand a strategy is tantamount to declaring it senseless, ill, outside rationality. But this is a classic cognitive fallacy: the mind projection fallacy, or the projection onto the world of one’s own inability to model it.

It happens with Putin, accused of being crazy because he invaded Ukraine, as if strategic brutality were synonymous with psychopathology and not a calculation of power. It happens with Trump, whose diplomacy has been systematically described as chaotic, impulsive, insane, as if it lacked method. But the reality is far less consoling: no psychiatric clinic is needed to explain certain behaviours of power. What is needed instead is strategic analysis, knowledge of communication patterns, understanding of the logic of deterrence, pressure, and the construction of narrative frames.

Theobsession with the ‘madness’ of leaders is also a way of dereliction of duty: if they are mad, there is nothing to understand or predict. But international relations are not a consulting room. They are a system of complex interactions, fuelled by interests, perceptions, fears and narratives. And it is precisely here that the figures of Putin and Trump offer two opposite but complementary examples of the strategic use of communication and force, not psychological deviance.

Putin and violence as a rational language of power

The idea, widespread in Western journalistic contexts, that Vladimir Putin is a ‘madman’ or a ‘crazed lunatic’ is a simplification as convenient as it is epistemologically fallacious. This attempt to ‘psychologise’ or even ‘pathologise’ the Kremlin leader responds more to the narrative needs of an anxious public and bewildered commentators than to a well-founded analysis of international relations and strategic communication. In reality, the violence Putin enacts is not a symptom of mental dysfunction, but a rational language of power, with very precise codes and purposes.

To understand the logic of Putin’s action, one must start from his worldview – an ideological and historical framework that does not merely rationalise war, but legitimises it as an ordering instrument of a new geopolitical balance. Putin does not improvise. His narrative is structured around an instrumental use of history: rewriting the past serves to legitimise territorial claims, consolidate internal consensus and project a consistent image of intransigent leadership.

Emblematic is the July 2021 document, entitled ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, in which Putin meticulously expounds the thesis that Ukraine and Russia are, in fact, one nation broken apart by historical mistakes – in particular those of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who, by recognising the right to secede, created an ‘unnatural’ condition for Russian imperial unity. This narrative is not merely a personal delusion: it is a rhetorical device constructed to justify an imperial reintegration action masquerading as historical rectification.

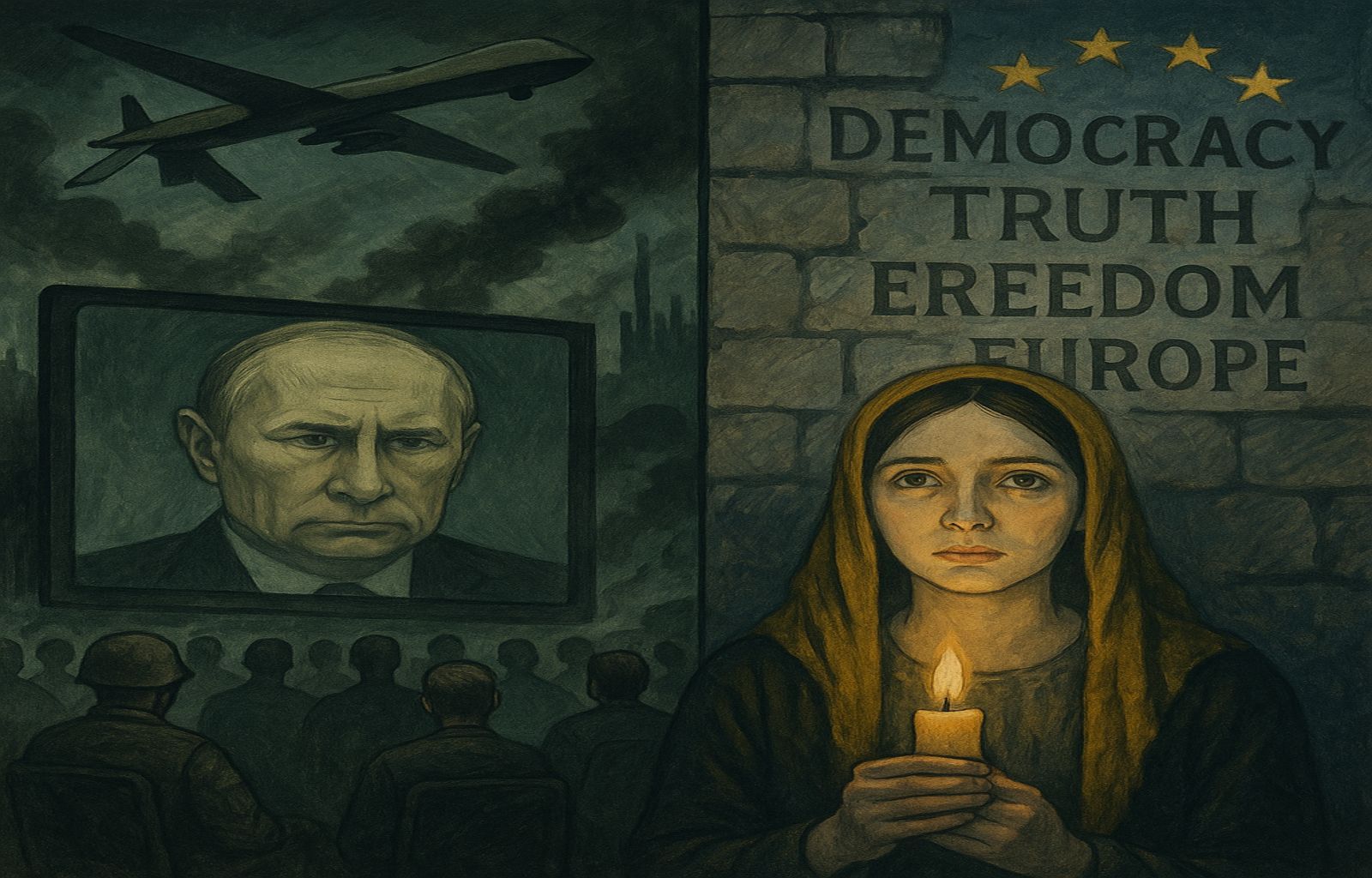

From a communicative point of view, Putin uses historical rhetoric as an instrument of collective mobilisation. He does not merely ‘narrate’ the war: he discursively constructs it. Each of his speeches is littered with references to the Second World War, the ‘Great Patriotic War’, the defence of the ‘Russian identity’ threatened by the West. The external enemy (NATO, the liberal West) is described as corrupt, decadent, incapable of sacrifice – a way of opposing the alleged moral weakness of the adversary with the purity and resilience of the Russian people.

This logic is not new: it finds precedents in the Stalinist use of historical propaganda to justify the construction of the Soviet empire. But Putin readjusts it to the coordinates of the 21st century, in a context of hybrid warfare and global narrative competition. The war in Ukraine is not just a conflict of arms, but a conflict of symbolic legitimacy: Putin must convince the Russian population that the war is just, necessary and defensive.

The symbolic value of performative power

This is where the performativity of power comes into play. Putin’s public appearances – from the packed stadium to the solemn speeches – are not mere media events, but acts of political liturgy. Crowds, flags, patriotic music, religious and constitutional references (such as the Gospel or the 1993 Constitution) compose a theatre of sovereignty. The aim is to convey a sense of unity and moral purity in the face of a corrupt and treacherous West.

Even the vocabulary chosen – with the deliberate use of words like ‘genocide ‘ – is designed to achieve legal and moral effects on an international level. Genocide is a crime of ius cogens, capable of justifying military interventions and building moral legitimacy for the defence of minority populations. Declaring that Ukraine is committing genocide against the Russian-speakers of the Donbass is therefore not mere rhetorical hyperbole, but a strategic attempt to redefine the legal terrain of the conflict.

This justifying narrative is not incidental to war, it is war. In international relations, physical violence is only one dimension of power. The other, equally decisive, is symbolic domination. Power is not only the ability to destroy the adversary in the field, but also to impose an interpretative framework that makes that destruction legitimate and even necessary.

When the Western media reduce Putin to a ‘ madman’ or a ‘sick person’, they slip into a mind-projection fallacy: they project their inability to understand an alternative political logic onto the opposing leader, turning him into a clinical anomaly. But this pseudo-psychiatric diagnosis is a methodological error. Not only does it prevent a rational analysis of Russian strategy, but it risks underestimating its internal coherence and mobilising power.

In reality, Putin is not irrational at all: his worldview is dark, illiberal, neo-imperial, but consistent. It is a strategic project of revisionism of the international order born out of the end of the Cold War, aimed at redefining spheres of influence and limiting the expansion of the liberal West. Violence is not a mistake, nor a failure, but an ordering tool, part of an established repertoire of power politics.

Understanding Putin means recognising that the war in Ukraine is not just a failure of diplomacy, but its continuation by other means. It is not the folly of one man, but the coherent manifestation of a power system that integrates narrative, symbolism, threat and violence into a single strategic language. Only by recognising the internal rationality of this language can we hope to effectively counter it diplomatically, informally and militarily.

Trump and performative diplomacy: the art of the deal as strategic spectacle

Donald Trump’s approach to foreign policy is an exemplary case of performative diplomacy, a strategy in which negotiating power is built not through the accumulation of traditional diplomatic capital, but through the staging of force, unpredictability and extreme personalism. Trump has consistently operated on the assumption that the perception of power matters more than its material substance, and that narrative is the real strategic arena in which victories and defeats are decided.

The conflict between Israel and Iran in June 2025 offers a privileged prism to observe this logic in action. The sequence of events is in itself revealing: the United States, after a week of ambivalent rhetoric, ordered precision bombing raids on Iranian nuclear sites. But the very nature of these attacks betrayed their essentially signalling function: the bunker-buster bombs hit sites that had been evacuated in advance thanks to an American warning, while the subsequent launch of Iranian missiles against the al-Udeid base in Qatar was anticipated and negotiated, ensuring no casualties.

Trump interpreted this military choreography as a drama of which he was at once director, protagonist and narrator. As soon as he left the Situation Room, he phoned Netanyahu to impose a ceasefire, while his envoy Steve Witkoff spoke with Iranian Foreign Minister Araghchi. Not content, he then announced the end of hostilities on social media, celebrating a diplomatic success for which he claimed all credit. The whole process was not an attempt to stabilise the region in the traditional sense, but a media operation designed to consolidate the presidential image as a quick and effective fixer.

This extreme personalisation of diplomacy represents the transposition of the logic contained in his famous book The Art of the Deal into foreign policy. For Trump, negotiation is never just a confrontation of interests, but a theatrical act, in which the control of the narrative frame is decisive. It is about producing a narrative in which the opponent is forced to react to his own moves, where uncertainty and the threat of escalation generate leverage, and where the resolution – however partial or fictitious – appears as the fruit of his own charismatic leadership.

But this very style carries deep structural risks. Spectacular transparency – the fact that everyone could see how the US forewarned Iran, or how Iran agreed to its symbolic retaliation – undermines the credibility of the most important element of deterrence: uncertainty. In diplomacy, the threat works when it appears credible and potentially devastating. Showing that the conflict has been scripted reduces the fear of escalation, suggests to adversaries that the price of certain provocations can be managed and negotiated in advance.

The Israeli-Iranian crisis was no exception. Israel itself, despite having obtained American tactical support, found itself forced to accept a ceasefire imposed by Washington, revealing a political limit to its pre-emption doctrine. Iran, despite the damage it suffered, was able to flaunt a symbolic response, saving face in front of its public opinion and remaining essentially free to continue – albeit slowed down – with its nuclear programme. Trump’s performative diplomacy has produced an unstable balance: no definitive loser, but no certain winner either.

Trumpian disruptiveness towards the allies, who open their eyes (?)

This apparently disruptive communicative style reveals its fragile side also in relations with allies. With the European Union, Trump has adopted the same blackmailing and theatrical logic. Tariffs, presented as tools for ‘correcting’ trade imbalances, functioned as more political than economic threats of retaliation. Their function was not only protectionist, but also disciplinary: to show the US ability to strike at European interests and force Brussels to make concessions on military spending or strategic cooperation.

But this dynamic, while fruitful in the short term, has generated resistance and reflection within the European camp. Trump’s unscrupulousness has helped to reawaken, at least in words, the debate on a European strategic autonomy: an awareness that subordination to the US carries a political price, especially when Washington changes mood with each change of administration. Here again, performance diplomacy has revealed its double face: powerful negotiating leverage, but at the cost of exposing the rules of the game, pushing opponents or even allies to seek alternatives.

Not even in the relationship with an interlocutor like Putin has Trump’s strategy proved to be risk-free. The American president tried to personalise the relationship with the Russian leader, focusing on bilateralism and the exclusion of Europe from the decision-making tables. But Putin played the same game, using history, imperial victimhood and anti-Western rhetoric to legitimise his own revisionist agenda. In this competition of narratives, Trump ended up granting Moscow what it wanted most: the recognition of strategic parity and the right to its own ‘space of influence’. Performative diplomacy, based on personal charisma, clashes with the toughness of adversaries who are equally familiar with the symbolic value of moves and know how to exploit every narrative concession to strengthen their internal power and negotiating position.

The Trumpian approach is therefore not the result of madness or casual inconsistency. It is a deliberate strategy of communicative power, in which every crisis becomes an opportunity to reinforce the leader’s image, every negotiation a stage to reassert American hegemony. But it is a strategy with a limited horizon, which trades tactical success for strategic stability. Where traditional diplomacy seeks to build trust, manage ambiguity, maintain opacity about the true limits of power, Trump’s performative diplomacy is based on the dramatic unveiling of intentions, explicit blackmail, and the construction of binary scenarios of victory or defeat.

The result is that, in the short term, this logic can achieve significant results: forcing Israel into a ceasefire, humiliating Europe with tariffs, containing Iran with symbolic bombings. But in the long run it reveals its fragile nature: once the mechanism is understood, adversaries may adapt, allies may try to emancipate themselves, and American prestige may be eroded.

Thus, the most dangerous legacy of Trumpian performance diplomacy may not be immediate destabilisation, but the normalisation of bluffing as an instrument of international governance. A strategy that, by revealing too much of itself, teaches everyone how to play – and, in the end, how to resist.

Conclusion: beyond the psychiatry of power, towards structural analysis

The media obsession with reducing the complexity of political power to the ‘madness’ of leaders is a reflection of analytical laziness, a reassuring alibi that avoids the hard work of strategic understanding. Painting Putin as a paranoid imperialist or Trump as an irrational narcissist offers moral relief to the public, but provides no useful tools for anticipating or managing international crises.

The reality, as the two analysed trajectories show, is far more sophisticated. Vladimir Putin embodies a classically strategic approach in which force – even brutal force – becomes a rational language for the redefinition of borders, spheres of influence and power hierarchies. His historical rhetoric, his selective use of the imperial past, and the nuclear threat are part of a well-coded model of coercive communication that serves not only to justify military action, but to prepare the diplomatic and psychological ground on which to redefine the European order.

Donald Trump, on the contrary, has constructed an unprecedented form of performative diplomacy, in which foreign policy becomes a personalised spectacle, an orchestrated narrative for mass consumption and psychological pressure on interlocutors. His behaviour in the latest Israeli-Iranian crisis was a plastic example of this: pre-announced bombings, symbolic retaliation, ceasefires announced via social media, all turned into a highly emotional script. Not a disorderly delirium, but a lucid calculation: exploiting unpredictability, amplifying one’s political brand, conducting negotiations on the terrain of public perception instead of the technical one.

These are not episodes of individual madness: they are coherent strategies, rooted in precise cultural, institutional and systemic contexts. Putin acts as a post-Soviet tsar, with a hierarchical vision of international relations and a security logic centred on control of space and strategic depth. Trump operates as an entrepreneur of political communication, convinced that the art of negotiation consists of shock, explicit threat, and the creation of binary dilemmas from which to extract asymmetrical advantages.

Communication and strategy: analysing performance diplomacy to understand the world

In this sense, the real analytical error is not to justify these choices, but to trivialise them. Performative diplomacy, as well as strategic coercion, are adaptive responses to an international system that, after the end of bipolarity, has become multipolar, fragmented and hypermediated. In an environment where classical deterrence has become less predictable and political legitimacy more contested, leaders are forced to negotiate not only with their peers, but with public opinions, markets, and social networks.

Strategic communication is no longer an accessory of diplomacy: it is diplomacy. It is no longer mere exchanges of verbal notes or treaties signed behind closed doors, but a continuous process of storytelling, framing and symbolising the threat and the offer. Crises are resolved not only on the military or economic terrain, but in the battle for meaning: to establish who appears reasonable and who aggressive, who is defending an order and who is subverting it.

Therefore, to reduce Putin to madness or Trump to delirium is more than a mistake: it is a mind projection fallacy, a confusing our inability to understand with a pathology of the other. It means ignoring the internal rules of a game that, no matter how ruthless or cynical, remains logical and consistent to its ends.

The task of the strategic analyst is not to medicalise the enemy, but to decipher its logic, to anticipate its movements, to construct realistic scenarios. It is not to moralise or absolve, but to understand. Only by recognising the internal rationality of these strategies – their ability to generate consensus, exploit fears, impose frames – can we hope to develop adequate instruments of containment, deterrence and, in possible cases, compromise.

In an increasingly opaque, unstable and competitive international system, this is the real challenge: to move from a psychologising and moralistic reading to a structural and ruthlessly realistic analysis. Because performative diplomacy and force strategy are not aberrations of modernity, but sophisticated adaptations to a world where communication is the battlefield and perception is power.

Ultimately, there is no need for a psychiatric diagnosis of global leaders. What is needed is a strategic competence capable of distinguishing bluff from real threat, staging from the will to escalate, theatrics from substance. Because only those who can read the script behind the stage can truly make foreign policy in a world that – precisely because it seems to have gone mad – does not admit of misunderstandings.