Tensions in the Aegean: Ankara challenges Athens with an alternative maritime map

At the heart of a decades-long geopolitical dispute, Turkey has re-launched its challenge to Greece by submitting its own maritime planning map to UNESCO, in direct opposition to the Maritime Spatial Planning Plan (MSP) published by Athens last April. The new Turkish step fuels tensions over the extension of maritime jurisdictions in the Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, two strategic areas not only for geopolitical reasons, but also for economic and energy reasons.

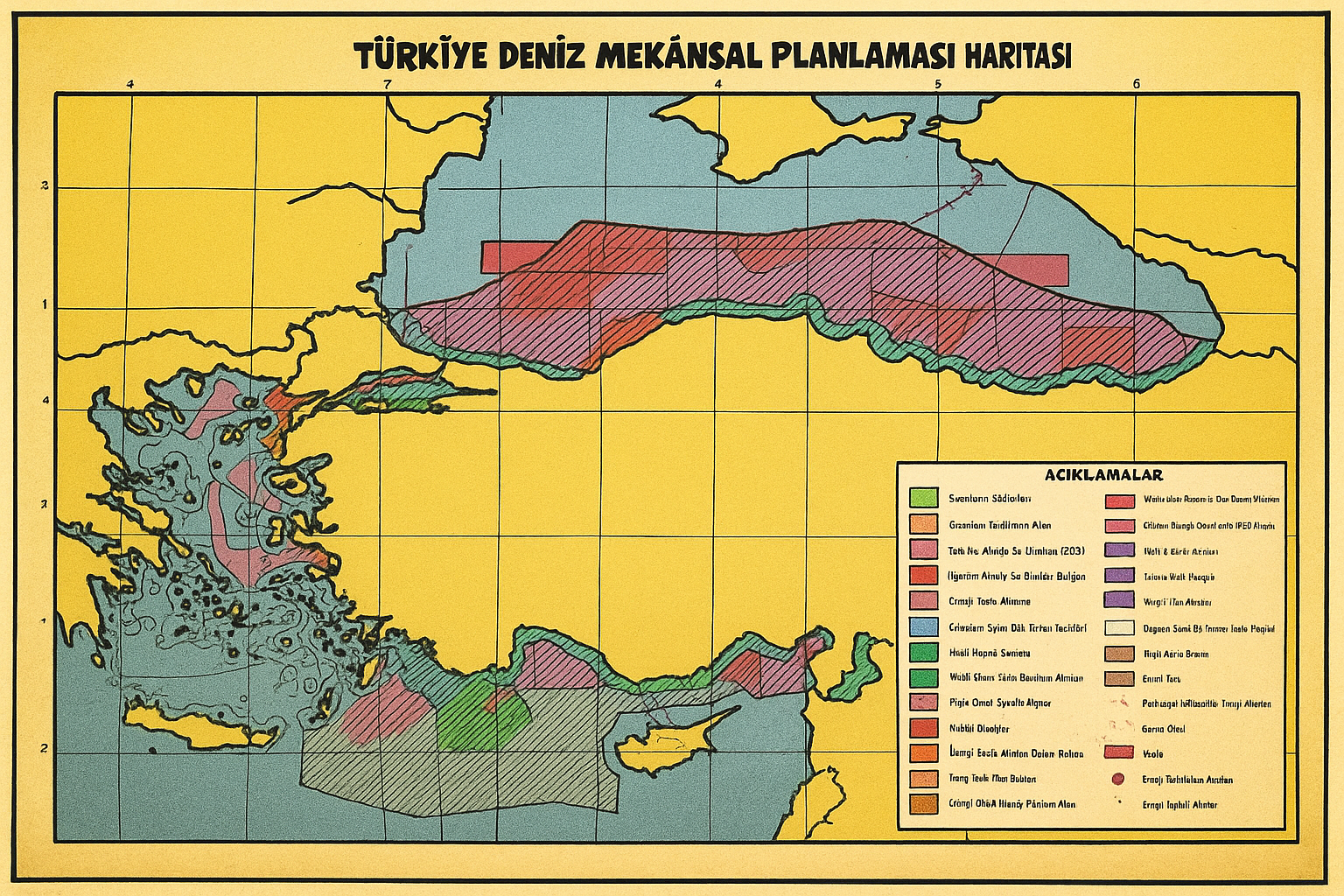

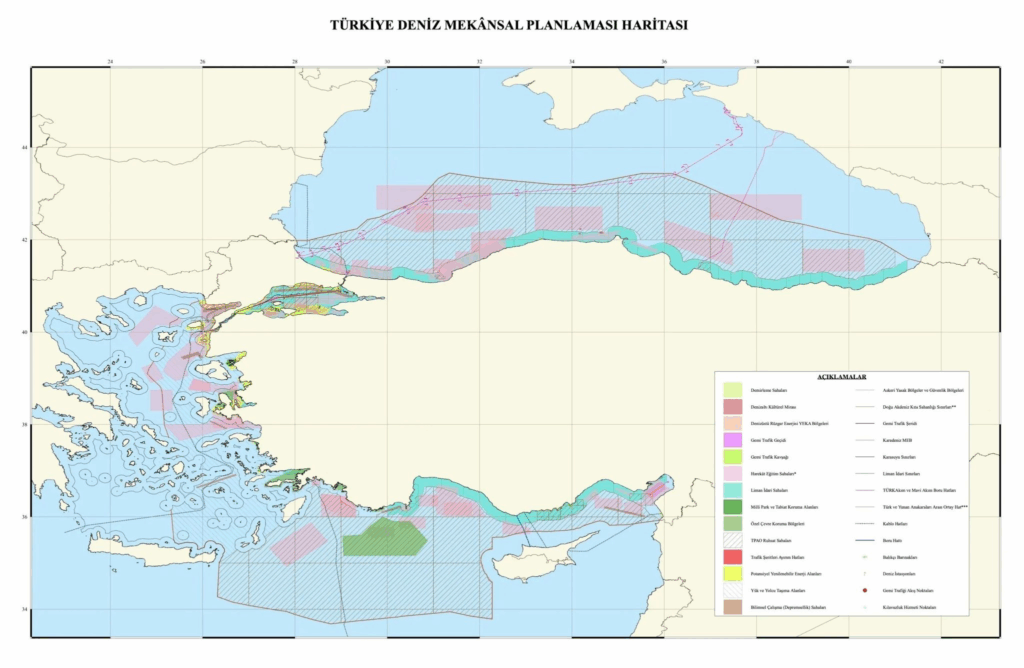

The map presented by Erdogan’s government – drawn up by Ankara University – reflects historical and established positions of Turkish diplomacy, and stands in stark contrast to the Greek view and the generally accepted view of international law. Specifically, Turkey disputes the right of the Greek islands to have a full Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf beyond 6 nautical miles of territorial waters, an argument that goes against the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which Greece adheres but which Turkey has not ratified.

A cartographic challenge to Greek sovereignty

One of the most provocative elements of the Turkish map is the division of the Aegean Sea almost in half, incorporating large maritime areas around numerous Greek islands into the alleged Turkish jurisdiction. In this way, the maritime rights of islands such as Chios, Samos, and even Rhodes and Kastellorizo are explicitly questioned. In addition, the map includes the borders under the disputed maritime memorandum signed between Turkey and Libya, an agreement that Athens and the EU consider illegitimate.

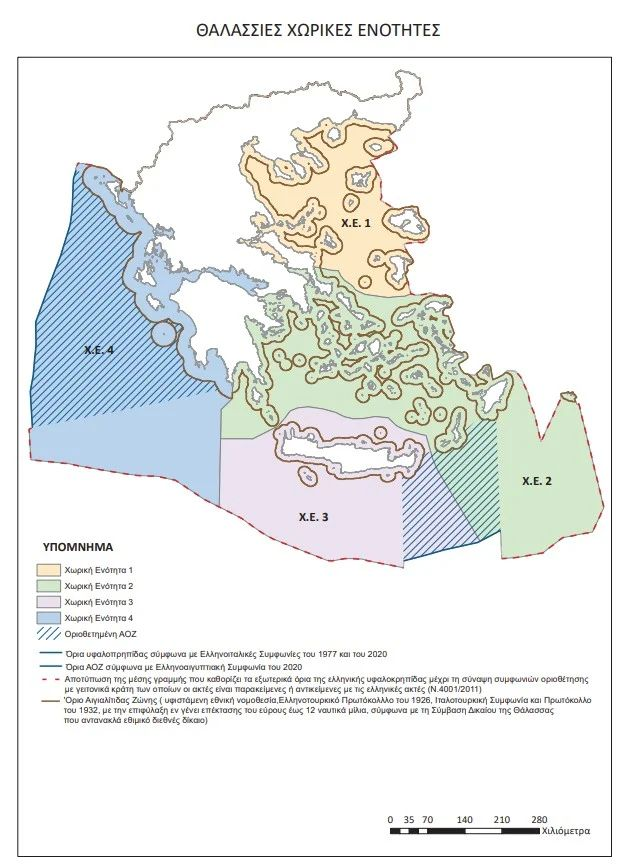

To this move, the Greek authorities respond firmly, supported by the official map of the national MSP, published in April 2025 by the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Environment and Energy. The Greek plan, also approved by the European Commission, fully recognises the legal effect of all islands, including Kastellorizo, and defines the Greek maritime space in line with international conventions. “For the first time,” the government emphasised, “our country officially establishes rules for the organisation of its maritime space, balancing ecological, economic and social objectives.”

The Eastern Mediterranean as a global test bed

Turkey’s revival of the dispute seems to have a clear strategic purpose: to assert its own vision in the international context, challenging the legitimacy of Greek delimitation even within UNESCO. Moreover, the map includes areas granted to the state-owned Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) for energy exploration, thus projecting an economic and industrial dimension within the diplomatic dispute.

The episode is part of a context already marked by ongoing frictions, but also by recent attempts at dialogue between the two countries. However, Ankara’s unilateral gesture risks undermining the timid signs of détente, reopening open wounds that date back well before the 2019 Turkish-Libyan memorandum.

At a time when the stability of the eastern Mediterranean is already being tested by wider crises, from the war in the Middle East to new energy routes, the dispute between Greece and Turkey over the sea is not just a bilateral dispute: it is a European issue, and ultimately a test case for international law.