Spain vs. NATO: from Pedro Sanchez demagogy, pacifism of convenience and free riding

In the seminal ‘The Logic of Collective Action’, Mancur Olson, economist and pioneer of public choice theory, illustrates a concept so limpid that it is often ignored: each individual has an interest in participating in an organised group only insofar as his participation brings him a tangible benefit; in other words, only if his conditions are improved compared to acting individually as a result of his participation in such a group, which always implies a certain contribution to the common cause. This principle also applies to groups of organisations or institutions, such as supranational organisations like NATO.

Driven by the innate attempt to maximise their utility and optimise their costs, members will always try to act as net beneficiaries, that is, as agents who benefit more than they contribute; in other words, they will always try to act as free riders. A bit like those who do not stamp their metro ticket because they are sure that they will not encounter any ticket inspectors and that the rest of the community will continue to bear the full cost of the service, guaranteeing it to those who take advantage of it. The success of any group depends exactly on how successful it is in discouraging and stemming this phenomenon, which is capable, to quote a maxim of Frédéric Bastiat on the nature of the state, of rapidly transforming a group into a ‘grand fiction through which everyone tries to live off the backs of everyone else’. This is the sacrosanct principle to which every net contributor appeals, whatever the circumstances, be it participation in the budget of the European Union or, as mentioned, that of the Atlantic alliance.

A defence at the expense of others

Speaking of NATO and the behaviour of its members, the Spanish government’s opposition to increasing defence spending to 5 per cent of GDP by 2035 is emblematic of an attempt to defend a position as net beneficiaries of a common good provided mainly through the efforts of others. The data are unequivocal: Spain spends just 1.3 per cent of its GDP on defence, well below the 2 per cent threshold agreed by the allies at the Cardiff summit in 2014, but would it be financially capable of sustaining greater outlays to reach the targets set? In this, the refusal of Pedro Sanchez’s executive appears to be a mixture of facile socialist demagoguery, riding on the mantras of the welfare state and pacifism of convenience, and the actual difficulty of finding additional resources for the purpose. The Spanish Prime Minister has declared that, to reach the 5% target by the 2035 deadline, 350 billion would have to be added to the state budget: a conspicuous figure, if we consider that, on average, a Madrid finance bill of the last 10 years amounts to around 490 billion. Even more pessimistic is the French magazine Le Grand Continent, which estimates instead that Spain would need to spend around EUR 65.3 billion more each year to meet the targets.

Pedro Sanchez, therefore, neither lies nor overestimates the economic effort required and the impact it would have on Spanish social and welfare spending if defence funding did not resort to increased borrowing and the consequent increase in the budget deficit. However, it does not at all open up the possibility that, in a country with worrying macroeconomic indicators, such as a debt/GDP ratio of around 102% and public spending of over 45% of GDP, there may be items of unproductive, sometimes even parasitic, spending that could at least be rationalised. This is an extremism that is not good for the Spanish economy itself, regardless of NATO’s opinion.

If, in Madrid’s eyes, the effort required by the allies appears insurmountable, it is because, in the area of defence and security, Spain has over the decades accumulated a chronic backwardness that it is now hardly able to make up, benefiting largely from the protection guaranteed by the investments of friendly countries. In short, if it has been able to increase the items of expenditure relating to the welfare state and to the maintenance of an enormous bureaucratic and administrative apparatus, it is also because, in terms of defence, it has enjoyed a conspicuous rent of position. In this, it is not alone: Italy, Canada, Belgium and other smaller members do not meet the 2% quota either, but all of them, bar none, have understood the importance of increasing investment and accepted the new agreement. An assumption of responsibility, this, which is certainly not without its sacrifices. For our country, for example, the adjustment to the new NATO targets is expected to result in an estimated 450 billion in additional expenditure over the coming decade.

Between demagogy and opportunism

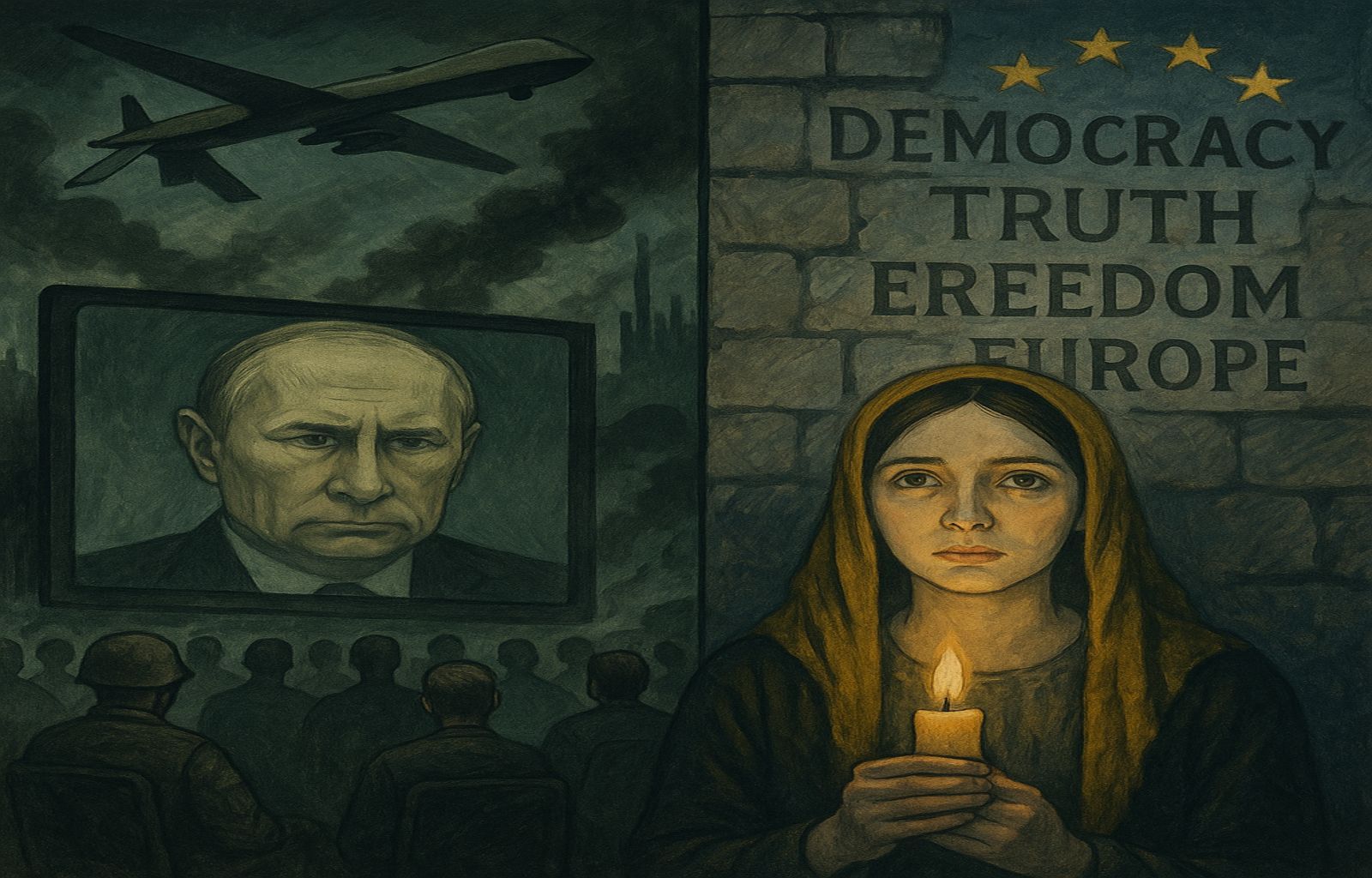

To speak of a ‘sovereign choice’ – invoking, among other things, a buzzword of certain right-wingers so disliked by progressive factions – is really unserious on Sanchez’s part. A coherent ‘sovereign choice’, if one is so at odds with one’s allies, would be to abandon NATO and do it with one’s own (and meagre) forces, leaving a militarily weak Spain alone on the international chessboard, in an era of geopolitical turmoil and with the multilateral system in jeopardy. Indeed, to argue that there is no need to increase military investment because there is no real danger of being attacked is to fail to understand (or pretend to) that, if today’s alliance members are virtually untouchable, it is precisely because a strong and predominant union in terms of armaments, resources and technology acts as a deterrent to anyone from the outside who might develop strange all-powerful lusts.

Investing means demonstrating to the powers with whom we have friction that the Atlantic pact is not a twentieth-century derelict on its twilight path, but a commitment that is even renewed and reinvigorated by looming threats. A serious and appreciable request, on the part of the Spanish executive, would have been to grant the country, as an exception, longer timeframes to reach the agreed targets, perhaps aiming, at first, at an already relevant 3.5%; timeframes in which to reform the machinery of the State and seize the opportunity to make it leaner and more efficient, freeing up resources and recovering, in the meantime, even a few GDP points.

Facade pacifism and populist harangues are just the fig leaf behind which the leader of an extremely fragmented majority tries to hide, in which the radical left’s impulses undermine the adoption of common-sense choices. Pedro Sanchez is caught between the anvil of the no-confidence motion of the parties furthest to the left and the hammer of an alliance asking Spain to become a little less of a free rider. Like any politician, his time horizon is that of an electoral round. In a country where there are so many voters whose standard of living depends on the state machine, putting the Leviathan on a diet means alienating a lot of sympathies. Surely, by persevering in this line dictated by a mere calculus of consensus, he will alienate far more among those who help keep Spain and the Spanish safe.