Putin prepares to make his war on the West eternal

Russia is reinforcing its military garrisons on its western borders, starting with those with Finland, thus following up on the threats formulated in the aftermath of the Scandinavian country’s decision to abandon its proverbial state of neutrality and join NATO.

But also confirming that the ferocious invasion of Ukraine is not just an episode of historical and cultural settling of accounts between neighbouring countries, but the bloody stage of a drift made up of imperial obsessions and securitarian paranoia.

Those who see for Europe a future of normalisation of relations with Moscow, assuming that the current conflict does not end with a macroscopic (and unacceptable to the West) violation of international law, ignore the signals that, for at least the past twenty years, i.e. since Putin’s intention to take root in the Kremlin’s gilded halls became clear, have been coming from a regime that has consciously chosen to look backwards, towards the late empire, instead of building the modern Russian nation, which was never born from the ashes of the USSR.

Americans and Europeans saw what they wanted to see

Land, language, culture and currency are elements common to every entity. But when the trajectory in international relations tilts under the weight of the instinct to dominate, control, and limit the sovereignty of others, we embark on a path strewn with war.

Some will argue that the United States has also been an empire. An empire built on military, economic and the political strength derived from these.

But it has also been an empire capable of self-criticism and eventually self-censorship, to the point of abandoning, by bipartisan will, the cynical and opinionated logic of the exporter of democracy. Sometimes with tragic results, as the retreat from Afghanistan, conceived by Republican Trump and implemented by Democrat Biden, has taught us.

In the meantime, it suited everyone not to see what was happening in post-Eltsin Russia.

For most, it was enough to portray the unknown KGB official who came to power in the last days of the last millennium as an ordinary member of a mediocre class of corrupt politicians, enriched by the chaotic privatisations of state companies in the 1990s, underestimating the unscrupulousness that was already clear from the criminal cynicism with which he organised the self-terminating bombings that justified the second Chechen war, with which the future Tsar inaugurated his career in the Kremlin.

Not seeing was convenient for the USA, whose attention was at first turned to the Indo-Pacific and especially the Middle East, also under the emotional impetus of 9/11. And which more recently would not have been able to accept the idea of a new Cold War, which would have prevented the leading country of the democracies from planning to relinquish its star as sheriff of the free world, to which the current American administration has, in all evidence, given a boost.

But it was also convenient for German-led Europe, which was too busy preserving its own prosperity built on Russian gas and oil and multi-billion dollar deals with the oligarchs who populated Putin’s court and cemented his power.

The invasion of Ukraine in 2022, even more so than the annexation of Crimea in 2014, was in this respect a wake-up call of sorts, making it clear how Russia, in feeling itself an empire, has never really given up and indeed sees its future as a dangerous continuation of what was once the Soviet Union. Not Gorbachev’s, mind you, but Stalin’s.

An imaginary version of the Second World War

This can be seen in the bombastic and pompous rhetoric with which the current regime extols the victory against Hitler and commemorates the millions of dead that that victory cost. Omitted in this reconstruction, however, are some not insignificant details.

The first of these is that while Europe was fighting Nazism, the USSR was merely fighting the Nazis, i.e. the traitors of that Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with which Moscow and Berlin had planned to divide Europe.

The difference, long ignored, is not insignificant, because it is the one that then delineated the opposite fates of the West and East of the old continent, that is, of those who aspired to build democracy on the rubble of war and those who instead only dreamed of replacing one tyranny with another.

Those deaths, celebrated by Russians and Russophiles, were therefore not a sacrifice for the freedom of the West, but a tribute of blood to the construction of a Reich of the East, which was then legitimised at Yalta.

And here we come to the reason why Russia is destined to remain a danger to democratic Europe, which can be found above all in the way the collective memory of those pages of their history is handled.

In fact, too often we are under the illusion that Vladimir Putin is some sort of accident, after which everything will return to some form of normality. But one only has to look at the events of the last years of the USSR’s life and the decade that followed to realise that he is actually the product of the failure of the bland attempt to democratise the country.

It is the expression of that part of society that never stopped wanting the return of the Soviet empire, whose collapse for Putin himself was ‘the greatest tragedy of the 20th century’.

Once in power, the new president has, not surprisingly, propped up and strengthened precisely that sentiment, nurturing nostalgic elements by controlling information, rewriting textbooks, building monuments, museums, memorials and major ceremonies, but also by banning organisations that might challenge the government narrative.

History teaches that such erosions of freedoms and the construction of de facto dictatorships, in order to be socially accepted, require an enemy, whose defeat requires draconian measures that are actually functional to the consolidation of power.

Enemies of Moscow were, for example, the Chechens, who carried out attacks, in reality self-made, against Russia in ’99.

So were the Georgians who, according to the Kremlin, carried out massacres in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, regions that were occupied in 2008. So were the Ukrainians, for whom the massacres of Russian-speakers in the Donbass and the oppression of those in Crimea were invented to authorise the 2014 military interventions. And all the more so today, who, planning to join NATO, in Putin’s delusions, are preparing to attack and destroy Russia.

Precisely the unprecedented ferocity in the conduct of the conflict in Ukraine, three years of death and devastation, tells us that today the enemy of the Russians, of all Russians, is us.

That Global West whose prosperity and democracies are the fruit of what, according to the czar’s grudges, is the undeserved victory of the Cold War.

That West of which the state propaganda speaks with contempt and which the government now makes no secret of wanting to oppose by all means, in the context of a hybrid war of which we only became aware when it bordered on the military level, but which had already been waged for years in the economic, political and information spheres. A war that aims at the disintegration of our societies and our annihilation, as part of the compensation for the unjust humiliation suffered by an empire that should never have disintegrated.

Monuments and repression

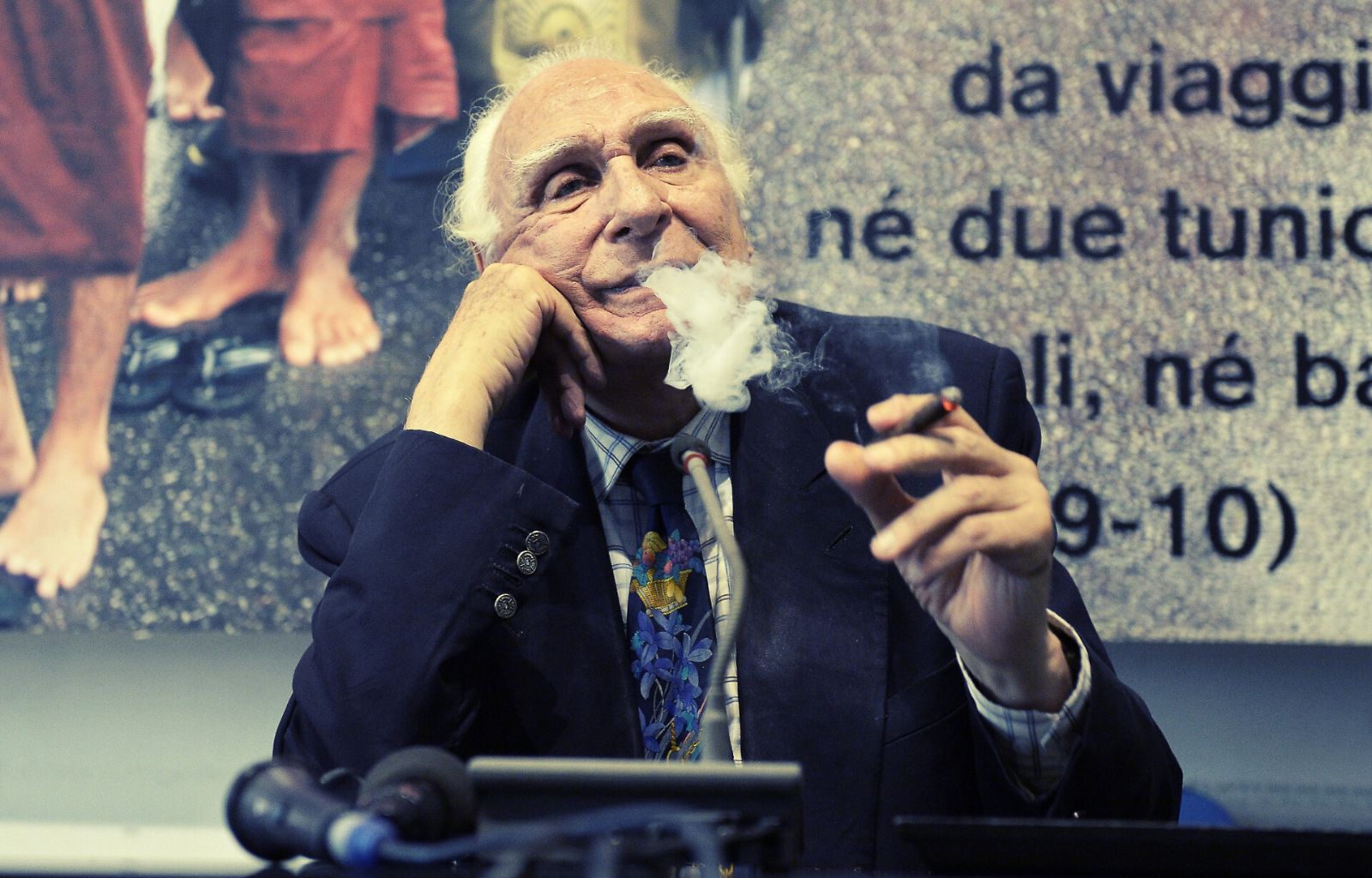

The political use of memory, precisely, of this grand plan is not only the most obvious telltale sign, but also proof of how the Putin regime has made ‘revenge’ (or rather revenge) an existential objective of the new Great Russia, to the point of making it a transgenerational mission, to which all the Russian people must contribute, thus establishing more than one point of contact with the ultranationalist Eurasianism propagated by thatAlexander Dugin, usually referred to as the tsar’s philosopher.

It is certainly no coincidence that monuments dedicated to Stalin (most recently a bas-relief in the Taganskaya station of the Moscow Metro), probably the greatest murderer in the history of mankind, are continuing to appear on the territory of the Federation, with the Kremlin’s placet.

Just as the outlawing of the NGO Memorial, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize 2022, whose task was precisely to keep the memory of Soviet horrors alive, starting with the massacre of the gulags, makes sense. Most of its archives are now inaccessible and the sites it managed, such as the shooting range at Butovo, are now run by the very loyal Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, which is sweetening its history in line with the regime’s demands.

In the meantime, revisionists and deniers rage in the national media, now setting the standard throughout Europe, including Italy. It is not difficult to come across journalists, politicians and opinion leaders who are prepared, for example, to downgrade the immense tragedy of the Holodomor (6 million Ukrainians exterminated by starvation between 1932 and 1933) to a mere example of disorganisation, or to deny the politburo’s responsibility in the Katyn massacre (22.000 Polish officers and intellectuals opposed to the communisation of the country, slaughtered in 1940), which the Soviet authorities had already tried in vain to attribute to the Nazis during the Nuremberg trials.

If you join the dots, you get a clear and worrying picture, which Europe first cannot afford to continue to ignore.

Russian society is being educated not only to believe itself predestined to be an empire, but also to believe that the celebrated millions of Soviet dead thrown into the furnace of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ have given it a kind of enormous credit with the West, which therefore owes Russia much of what it has.

The skilful suppression of Soviet crimes and the iron control of information that limits knowledge of Russian misdeeds of the last quarter century prevent that same society from understanding why that credit actually does not exist at all and why, on the contrary, Russia is now considered a terrorist and criminal state.

The Kremlin’s ruling dome is cultivating in a test tube the resentment of the Russian people towards a West portrayed as ungrateful and inexplicably Russophobic. Vladimir Putin, who in 2012 invented the ‘Immortal Regiment’, inviting Russians to bring portraits of their loved ones who fought against the Nazis, thus intends to make his war immortal as well, and make sure it continues after him. Making sure that the people, in the name of that war, choose a new Putin or, worse, a new Stalin.