Poor Canfora and Barbero. I understand them

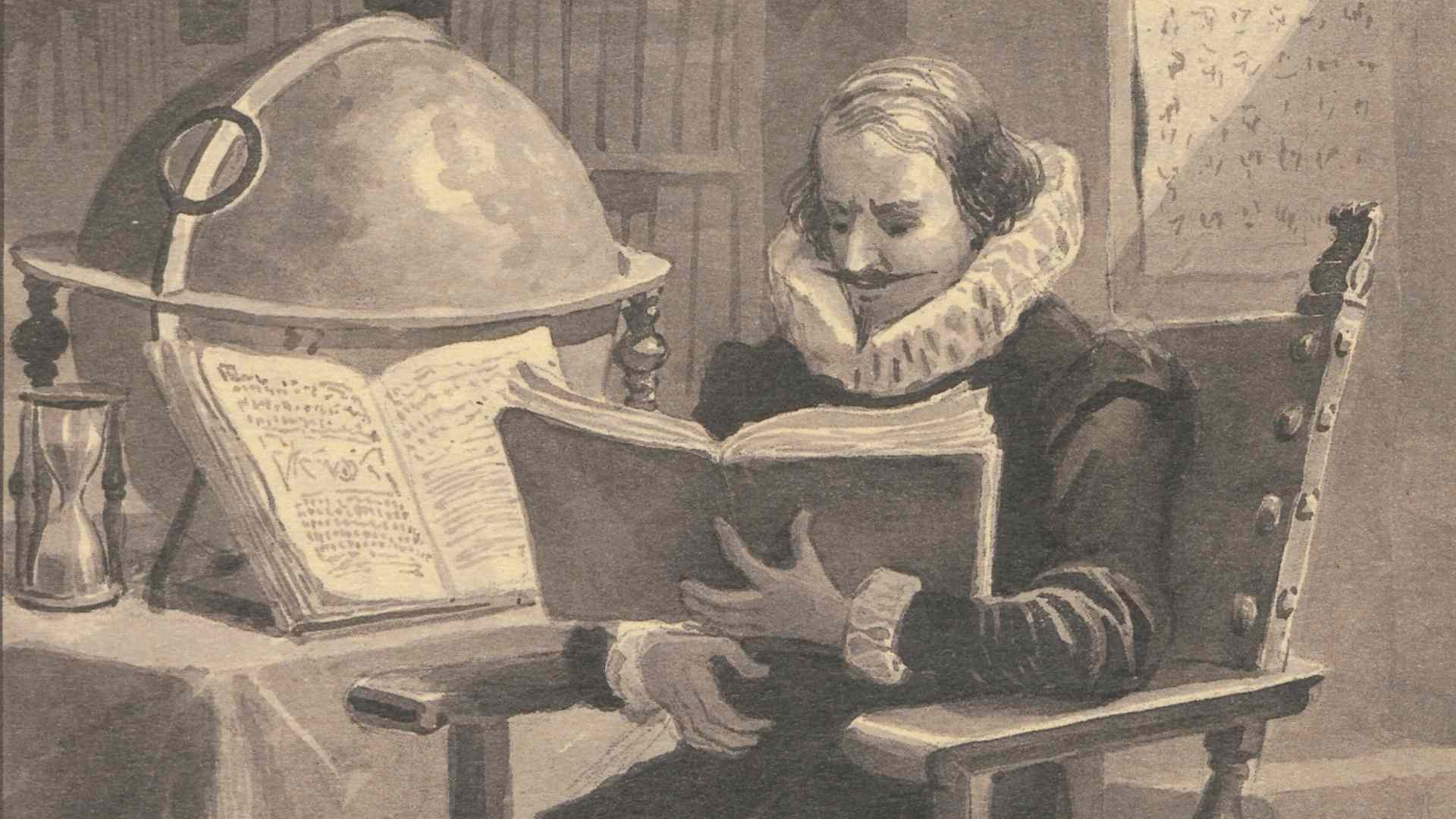

In Manzoni’s The Betrothed there is a character towards whom I feel a particular solidarity: don Ferrante, the Milanese scholar who hosts Lucia for some time before the arrival of the plague.

Owner of a rich library and versed in the natural sciences (as they were understood before Galileo), when the epidemic breaks out don Ferrante is unperturbed: thanks to his Aristotelian syllogisms he has irrefutably demonstrated that contagion cannot exist, since ‘it cannot be substance and it cannot be accident’.

In the end, of course, the plague kills him and his library ends up ‘scattered up the masonry’.

Don Ferrante is a human type we come across very often: the cultured man who, however, without realising it, has acculturated himself within a single scheme for reading reality.

As soon as reality jumps to the side and he steps outside that schema, his culture becomes a mental cage that prevents him from understanding it.

And the deeper his studies were in the past, the deeper his blindness to the present will be.

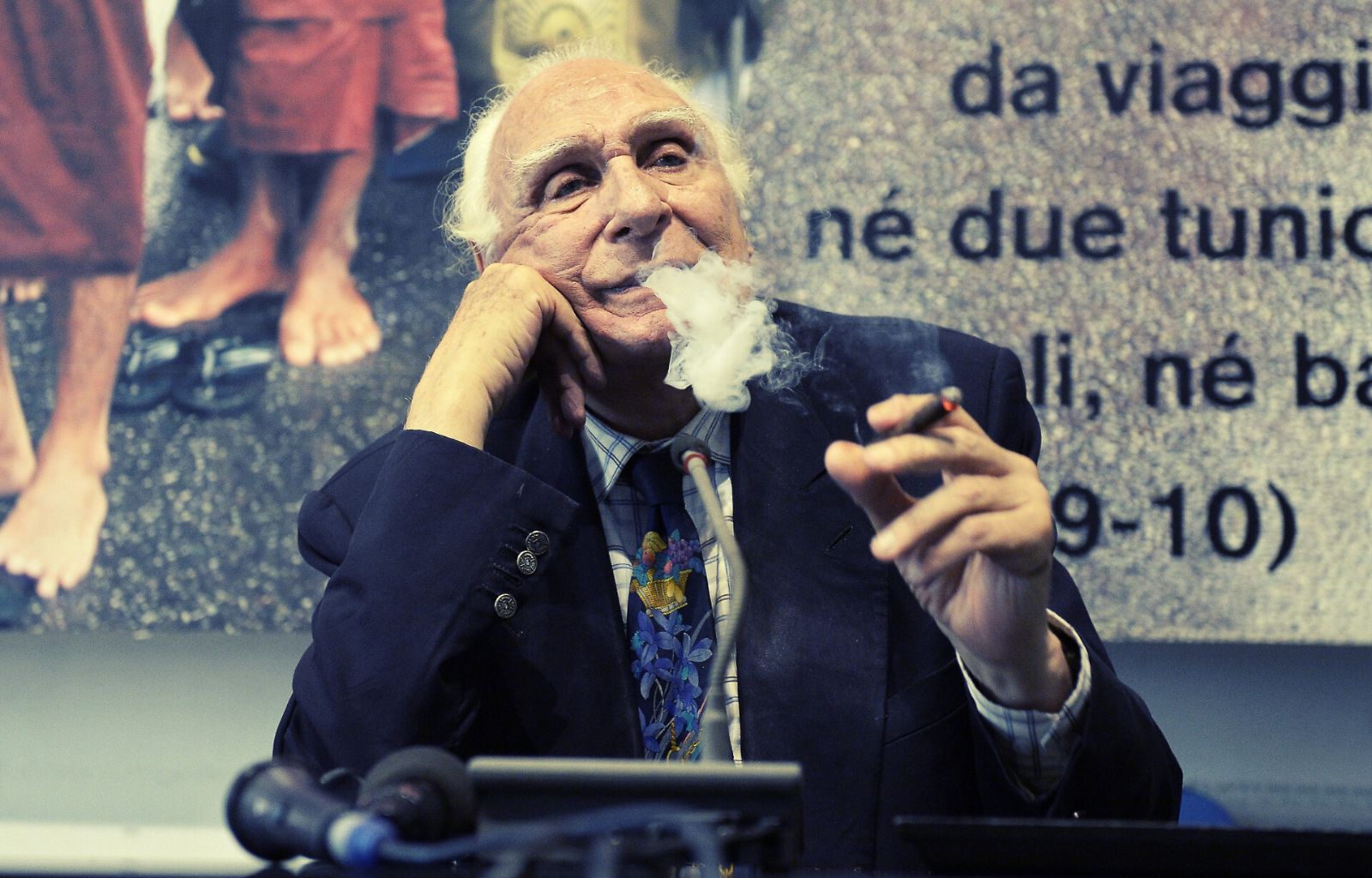

Now, my impression is that the generation of intellectuals like Canfora and Cacciari, together with that of their emulators brought to the fore by Barbero, has been experiencing its ‘Don Ferrante moment’ for some time now.

Not when confronted with bacteria and disease, but when confronted with the epochal historical changes to which the two invasions of Ukraine were the brutal reaction.

If these scholars supinely espouse Putin’s narrative on the war, spewing such rubbish as to put Don Ferrante’s on the non-existence of the plague to shame, it is not because they admire the Kremlin regime, nor because they regret Soviet communism (as is often insinuated with a certain simplicity).

It is, instead, because they are bewildered by a historical event that has shattered all their syllogisms and escapes their cultural schemata: the silent rise of the European Union as a continental and, in perspective, world power.

The European novelty

The European Union, despite having a thousand limitations, has created something objectively innovative.

For the first time, there is a power that expands by the free choice of the countries that choose to join it, and yet manages to make some great decisions that apply to all those who are part of it, just as it did in the ancient empires that arose from armed conquest.

The Union attracted the countries of Central Europe to itself in the 1990s, began to attract those of Eastern Europe in the 2000s, and now even attracts those of the Arctic, simply by existing.

No traditional imperialist power can keep up with that.

Think of Putin: with all his bloody wars, he has not yet managed to fully absorb even Lukashenko’s Belarus.

Let us think of Trump, who, if he wanted to make Canada his ‘fifty-first state’, would face a long, expensive and unpopular conflict: given his recent failure to occupy Afghanistan, I would venture to say impossible.

Think of how much the British Commonwealth has weakened over time – which helps explain the widespread regret over Brexit.

Think of the galaxy of fanatical and quarrelsome allies that Erdogan must rely on to restore hegemony over the former Ottoman Empire.

In such a framework, the bureaucratic rigmarole of ‘homework’ on the market and transparency with which one enters the EU appears, in its greyness, almost ingenious.

And even if, here and there across Europe, the Georgescu on duty were to get smarter, stop their pre-election delinquency, manage to run for office, win, and detach their states one by one from the Union and bring them into the Russian orbit, they would never have the same level of economic integration and power-sharing with Russia that they have today in the EU.

It would not take them decades to get there.

People attracted, regimes frightened

After all, to unmask the rhetoric of populists inside the EU, one only has to listen to that of populists outside.

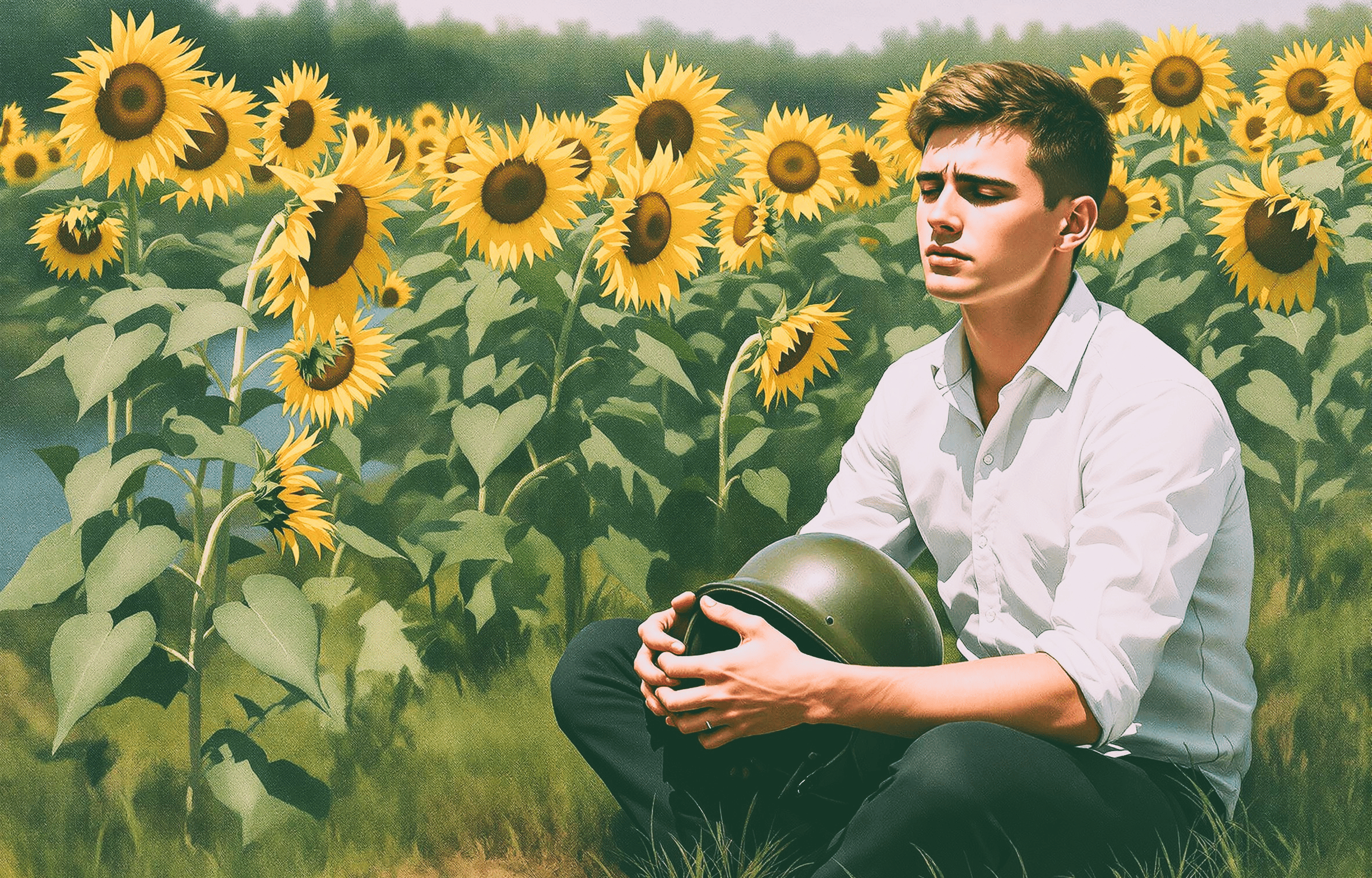

The surrounding peoples know perfectly well that by joining they would enjoy more protection, more prosperity and more freedom, and so Putin’s local vassals, such as Janukovich in Ukraine, Vucic in Serbia and Ivanishvili in Georgia, have never openly questioned their desire to join.

When Janukovich showed his true colours and tore up the partnership agreement with Brussels to sign one with Moscow, a crowd 30 times larger than the one that took the Winter Palace and 160 times larger than the one that took the Bastille took to the streets to oust him.

Putin reacted by invading Crimea and the Donbass, and justified himself with fears of NATO advancement.

But ten years later Finland joined NATO, and Putin did not move a finger.

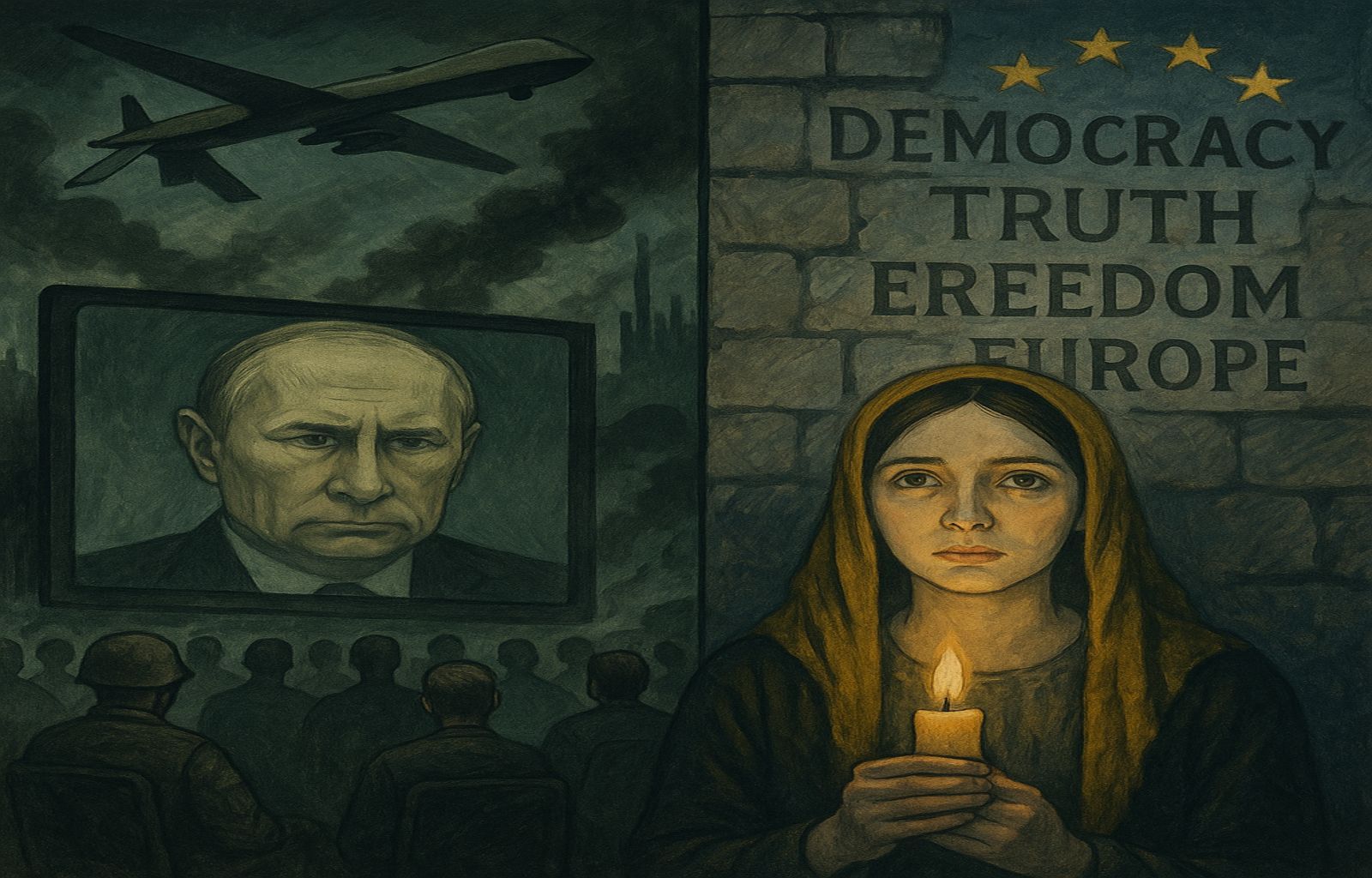

Evidently the problem was another advancement: that of liberal democracy.

The problem was the transformation of the old Soviet space into the new European space, which could now only be prevented by cannonade.

‘Grey bureaucrats’ or dangerous ‘fascists’? The short-circuit of propaganda

In short, let’s not beat about the bush: the reunification of Europeans under the crown of stars is a geopolitical project that for ease, effectiveness and acceptability annihilates any rival project, from Putin’s ‘Eurasia’ on down.

For the old empires, this alien creature of the 21st century is a veritable nightmare.

They ridicule it in words, speaking of a ‘Europe of bureaucrats’ or a ‘Europe that counts for nothing’, but in deeds they do everything to disintegrate it or at least contain it.

In this they show themselves to be more lucid than Don Ferrante: ‘Contagion does not exist, all right, but for superstition’s sake let’s face it anyway’.

The recent cartoon by the head of the Russian secret service is revealing. It says: ‘Euro-fascism is the common enemy of the US and Russia as it was eighty years ago’.

Not bad for a den of bureaucrats that counts for nothing.

Well, a similar headache must be seizing Canfora and Barbero.

For them, who were educated in the last century, in an academic climate shaped by Marxism,history has a set of ever-changing rules that determine its movements.

An expert on the Peloponnesian War can pontificate fluently on the Cold War or the war in Ukraine, because imperialisms all look alike, the economic interests behind wars all look alike, political ideals and religious beliefs are always ‘only apparent causes’ and never ‘remote causes’ of conflicts, and so on.

A connoisseur of 20th century history can play at finding correspondences between Merz and Hitler, or between Von der Leyen and Kaiser Wilhelm, without feeling ridiculous.

This labyrinth of courses and recursions, of structures and superstructures, of historia magistra vitae, has two advantages: it allows them to justify their own craft against (stupid) accusations of uselessness, and it allows them to turn into Youtube gurus or TV fortune-tellers, who divine in the darkness of the past the arcane secrets to explain the future.

But the European history of the last thirty years, where every single people from the centre or the east spontaneously tried to bind themselves to the ‘Brussels bureaucrats’, until the moment when Russia reacted by force, failed, sought backing in the disengagement of the USA and only succeeded in forcing the ‘Brussels bureaucrats’ to become an independent military power, is an inexplicable puzzle for those who still use the schemes of Thucydides or Marx.

“It cannot be substance, it cannot be accident…”

So, for our beloved professors and popularisers, it is an intimate and psychological necessity that Europe remain weak, that it leave its imperial provinces to Russia even against the will of those who live there, that it not fill the power vacuum left by the US, and so on. The survival of the historiographical categories they grew up with depends on it.

Add to this the understandable annoyance that a YouTube guru , accustomed to extolling the warlike exploits of Charlemagne or Genghis Khan, might feel at seeing a great power rise with the jaunty smile of Kaja Kallas, the placid eloquence of Mario Draghi, the sweaty T-shirt of Zelensky and the disco dances of Sanna Marin.

It is true that Charlemagne gave parties at the baths with a thousand guests (other than Sanna Marin) and that Genghis Khan never dismounted from his horse to reaffirm his role as military leader (other than Zelensky).

But you know, biographical anecdotes were never important to those who were focused on peering into the bowels of ‘spheres of influence’ or ‘class struggles’.

I understand them, the Canforas and the Barberos.

But precisely because I understand them, I invite them to adapt to the new reality.

Otherwise their erudition risks ending up like Don Ferrante’s books, forgotten in the euphoria of the city that escaped the plague.