Italy belongs to those who love it: citizenship, identity and a right wing that no longer exists

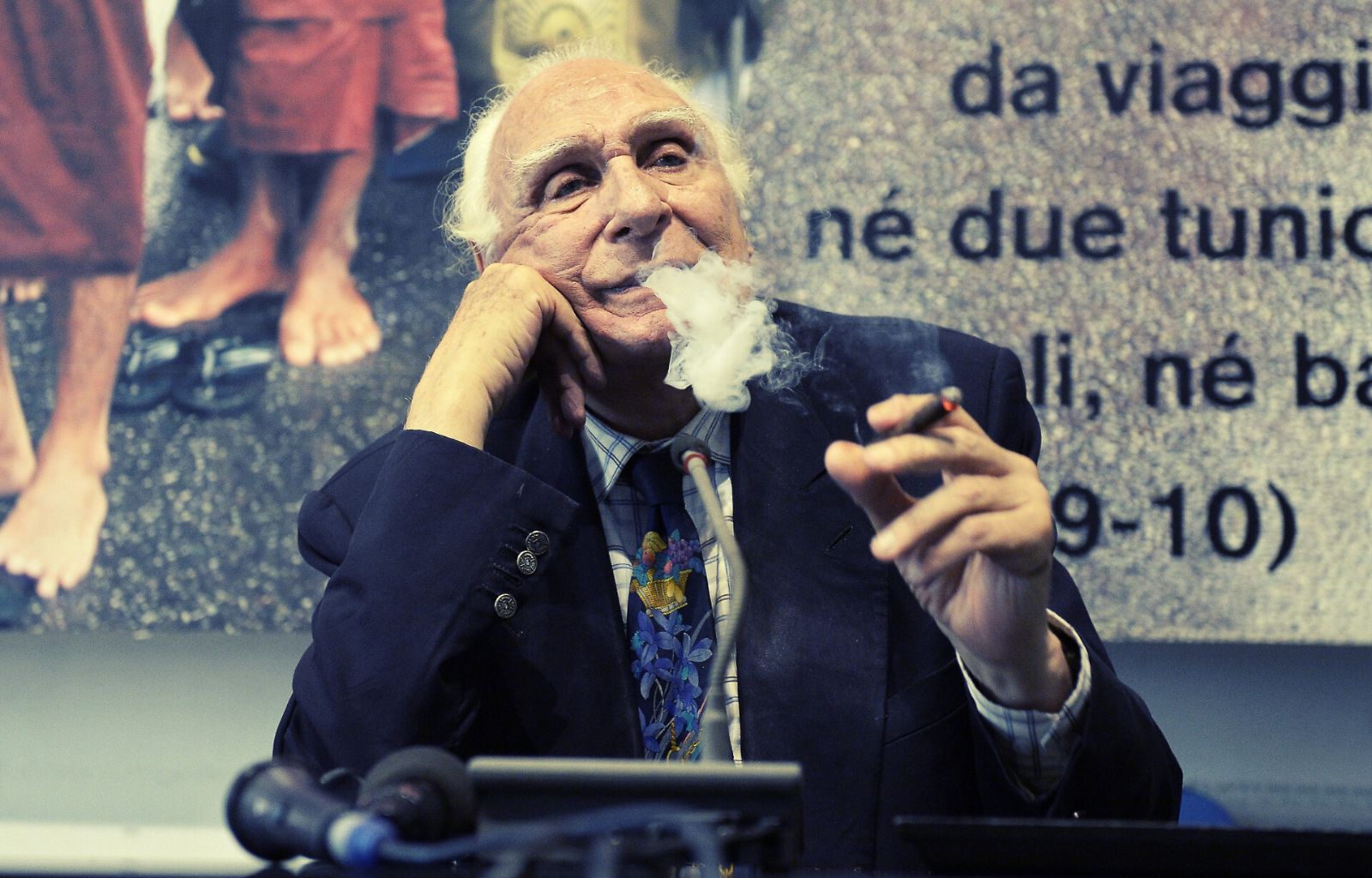

In 2010, now fifteen years ago, the then President of the Italian Chamber of Deputies Gianfranco Fini proposed that the children of immigrants could apply for citizenship at the end of a school cycle, without having to wait until they turn eighteen (from which, moreover, a few more years often pass before citizenship is actually granted). “At the end of a school cycle,’ this was Fini’s reasoning,‘ those children who are permanently in Italy, because they were born here, grew up here with their families, have the right to become citizens‘. So he was not proposing an automatic ius soli, but a citizenship linked to concrete elements of integration: education, family, stable permanence in the country. On that occasion, Fini also uttered a phrase that caused much discussion: ‘Italy belongs to those who love it, not only to those with Italian blood‘. It was a phrase that struck me at the time and has stuck with me over the years, not least because it came not from a progressive leader but from someone who had led Alleanza Nazionale, a man who had grown politically on the post-Missina right. A right wing that simply no longer exists today.

Alongside that voice, in the same historical period, there was that of Mirko Tremaglia, another historical exponent of the Social Movement and then of Alleanza Nazionale, engaged in a different battle but equally linked to a vision of national identity: guaranteeing Italians living abroad the full exercise of their right to vote. After the amendment of Article 48 of the Constitution, it was thanks to Law 459 of 2001, of which Tremaglia was a promoter, that postal voting became a reality. The law provided that Italian citizens registered with AIRE could elect their representatives in parliament and vote in referendums directly from abroad, either by postal vote or, if they wished, in Italy. Tremaglia did not invent a new right, but made effective and enforceable what was already provided for in the Constitution, recognising that national identity could also live outside the borders, in language, in memories, in family and emotional ties. It is a choice that may seem questionable, and in some cases it really is: in purely theoretical terms, even those who were born and raised abroad, who do not speak Italian and perhaps would not even know how to point out Italy on a map can vote. But perhaps it is precisely in that choice, criticisable to be sure, but inclusive, that a broader and more symbolic vision of citizenship was manifested, understood as a bond, in the widest sense of the term, unless it is tragically understood as ‘inheritance of blood’ over the centuries.

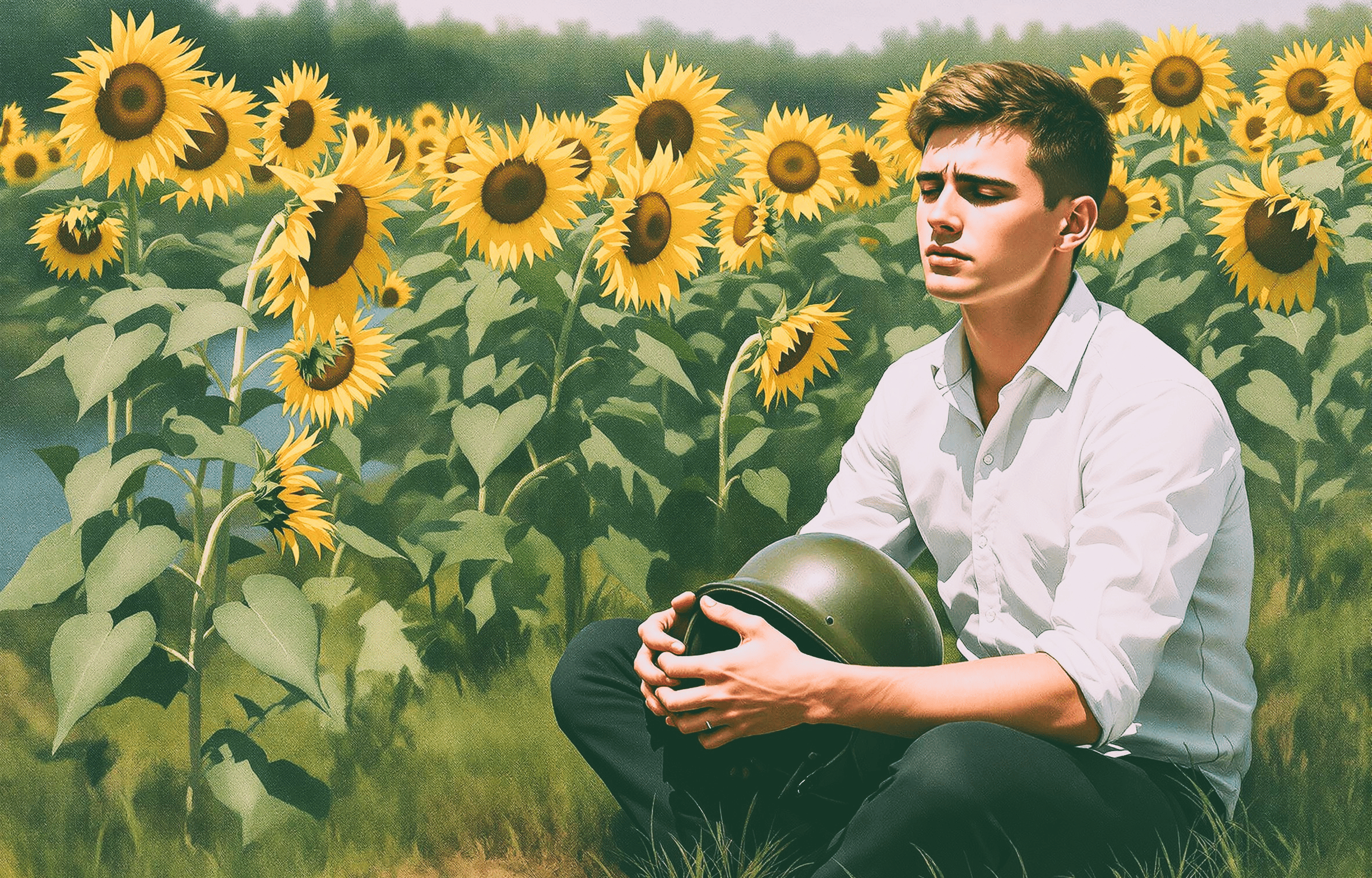

A concrete example, perhaps obvious but effective: Mario Balotelli. Born in Palermo to Ghanaian parents, raised in Brescia by an Italian foster family, he was never adopted. Italian in everything – language, school, culture, friends – he could not obtain citizenship until he came of age. He received it on 13 August 2008, the day after his 18th birthday. Until then, he could not play with the national youth teams, despite being one of the brightest talents of his generation. He refused Ghana’s offer and waited. He chose to represent Italy, the country he felt was his. As soon as he was a citizen, he was called up to the Under-21 team and then to the senior national team. On 28 June 2012, he led Italy to the European Championship final with a double against Germany. On that day, he was celebrated as a symbol of the nation. No one asked about his previous citizenship or his origins.

On that day, Balotelli was Italy.

But it is disturbing that certain concepts only find space when embodied by exceptional, famous or millionaire figures. That a champion is needed to legitimise the belonging of those who, every day, live the same experiences, without a spotlight, is a profound distortion. It is a theme that deserves a separate space, but it remains there: latent, urgent.

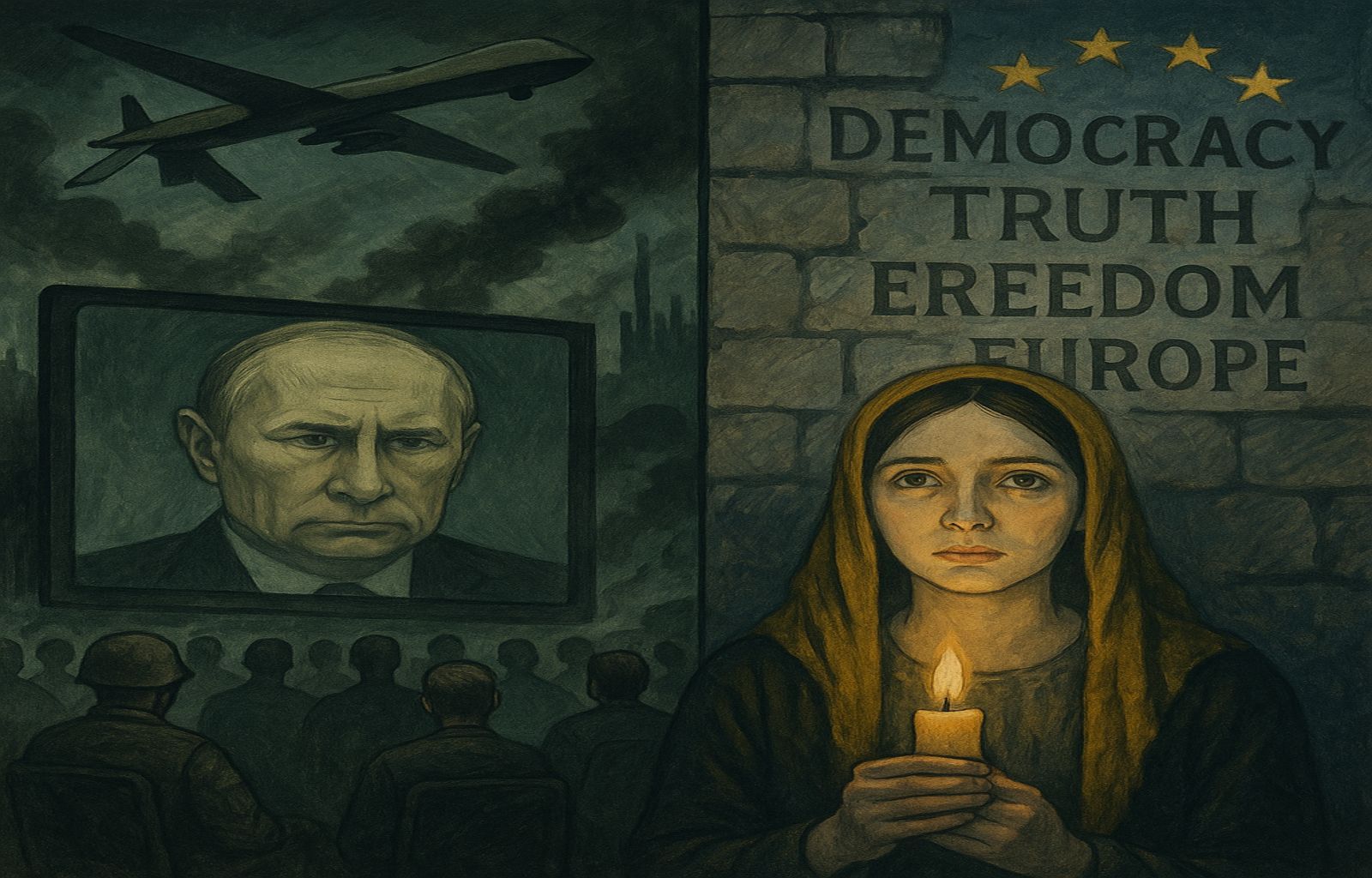

Fifteen years have passed since Fini’s words. In the meantime, the Italian right has lost all cultural awareness of that kind. The issue of citizenship, although legal, is first and foremost played out on a cultural level. It is not surprising that a more open proposal came from Fini: when the Right had a solid cultural structure, it did not fear complexity or confrontation. The different was not an enemy to be removed, but an element to be measured against. The crisis arises when identity is emptied of content and reduced to a reflection of the enemy. If identity only serves to say ‘we are not them’, then no law – neither inclusive nor restrictive – can really solve the problem.