‘In Russia fascist regime, but people now only want peace’, interview with Nobel Prize winner Oleg Orlov

“What should Europe do to help end the conflict in Ukraine? Keep in mind that most Russians are tired of this war. Then pressure Russia with sanctions and support Ukraine in every possible way: military, political, economic. To help Russia, first of all, it is essential to prevent Putin from winning the war‘.

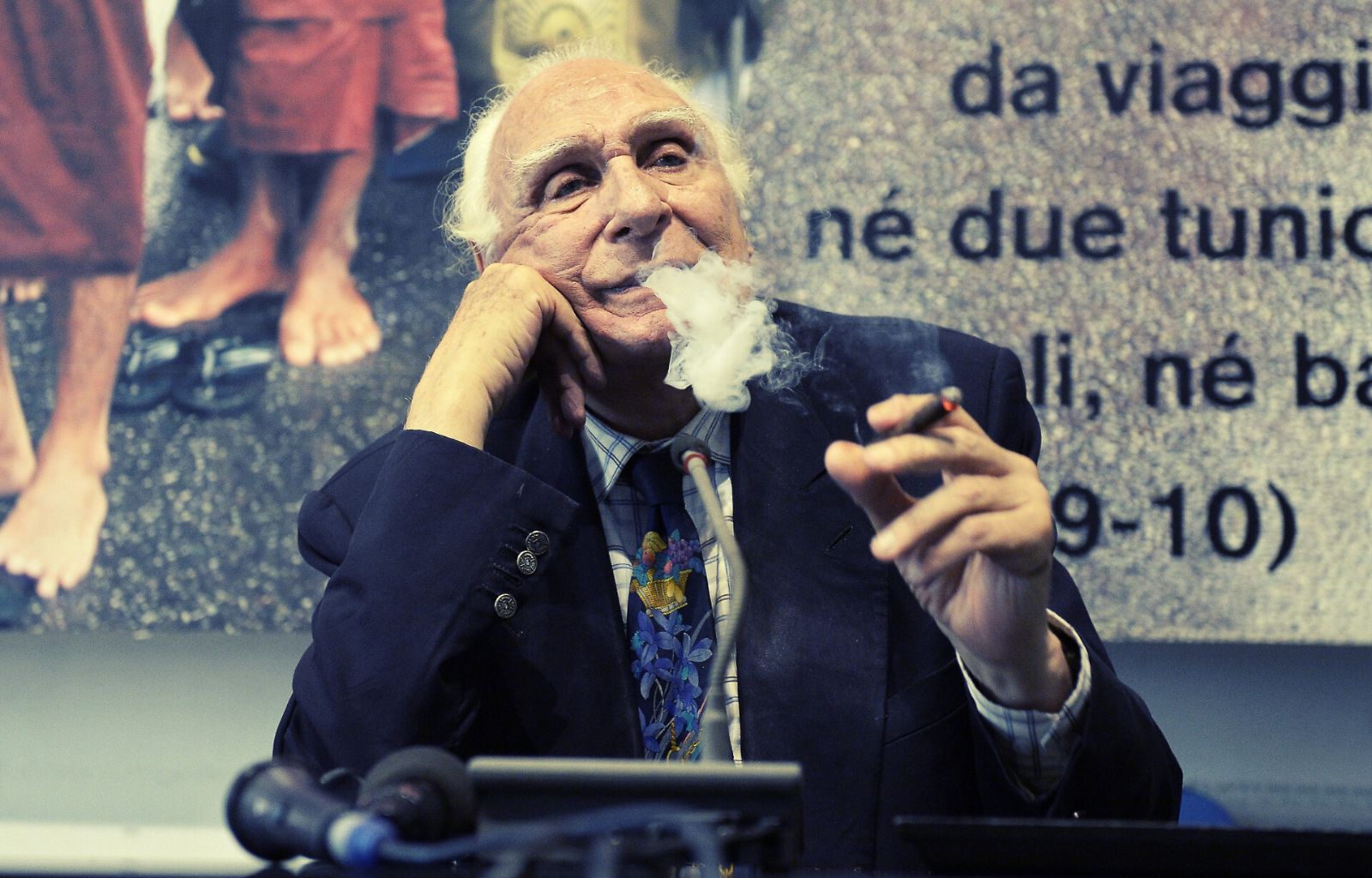

Oleg Orlov, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and co-founder of Memorial, is one of the most influential voices on the Russian human rights scene. The organisation he helped found – one of the most prominent in Russian civil history – has been officially banned by the Putin regime and has ceased its activities. For over 30 years, Orlov has been engaged in exposing war crimes, political repression and gross human rights violations, documenting suffering from Chechnya to Russian prisons. As early as 1995, he volunteered as a hostage in the Budënnovsk crisis to rescue civilians, a gesture that testifies to his unwavering commitment. In February 2024, he was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for describing Putin’s regime as ‘totalitarian and fascist’ in an article. On 1 August of the same year, he was freed as part of an exchange between Russia and the West: on the one hand, the release of unjustly detained activists and citizens; on the other, the return of convicted criminals such as the hitman Vadim Krasikov to Moscow. The establishment of Memorial was opposed precisely because – according to the Putin power – every critical memory had to be erased. After his release, Orlov immediately embraced two goals: concrete support for Ukraine and constant commitment to the release of those unjustly imprisoned.

I manage to exchange a few words with Orlov at the end of his five-day Italian tour, which ended in Rome with a whirlwind of institutional and non-institutional meetings, which also took him to Parliament, where he attended a hearing together with Leonid Soudalenko, of the Belarusian NGO Viasna, founded by Ales’ Bialiatski, now in prison, and Oleksandra Romantsova of the Centre for Civil Liberties in Kyiv. Together with Memorial, the other two share not only the aims of defending civil rights, but also a ‘collective’ Nobel Peace Prize, won in 2022.

The three also took part in a lively discussion at the Istituto Affari Internazionali, coordinated by Nathalie Tocci, during which Russia was obviously discussed, seen from different perspectives and inevitably the current conflict.

‘The Russian regime is a fascist regime,’ the 72-year-old activist began during the meeting, explaining how in making this statement, which is the same one used as a pretext to land him in jail, he relies on a definition of fascism produced by the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1995 at the request of then President Yeltsin.

Soon afterwards, he also explained that despite the closure, Memorial continues to operate clandestinely together with a network of organisations to offer material, economic and legal assistance to the many victims of systematic civil rights violations.

Is there therefore a piece of Russian society that resists the regime?

Absolutely. And I could give many examples. First of all, there is a free press, which, although physically outside Russia, works on Russia and is very well followed, despite the fact that these realities are going through a difficult phase thanks mainly to Mr Trump. I would like to make it clear, however, that the majority of Russians are tired and want peace, any peace. I would like to make that clear, because usually it is the very active minority that is fomenting this war that makes the news.

In the West, including Italy, the opposite is believed to be true, i.e. that Putin enjoys broad popular support in pursuing the conflict.

I wonder where you get this data from. No social survey can be considered reliable when conducted on a population that knows that even one wrong answer can land you in jail. The truth is that the regime is very afraid of popular reaction and possible discontent. Think for example of this war: the army would need many more men to crush the Ukraine, but Putin is careful not to propose a general mobilisation because when he did so there were even public protests about it. Similarly, he could force Russians to go to the front without being forced to pay them stratospheric salaries, but he doesn’t because he fears his popularity will suffer. Or the 18-19 year old enlisted boys could be sent to the front line, but this does not happen because their deaths would have a huge impact on public opinion. I repeat, Putin and his regime fear unpopularity

In Russia we have seen a certain historical revisionism on the part of the regime grow in recent years, with the exaltation of the tsarist and Soviet past. What is the reason for this Putin obsession with history?

For the regime, history is not a science, but a tool to be used for political purposes. I would add that it is a decisive tool. Everything is related to the past. We will win the war as in the past, we will be an empire as in the past. The very idea of the future that the Russian dictatorship is outlining for the country is entirely directed towards the past. But we also see this with Ukraine. Kyiv is the mother of all Russian cities, but one only has to read or listen to Putin’s interviews to understand how by manipulating history to justify the invasion, Ukraine is portrayed as a Russian invention.

But doesn’t this regime’s insistence on the great Soviet sacrifice against Nazism and the constant portrayal of a West ready to wage war against Russia risk fuelling a resentment of the population against Europe?

Yes, it is possible, and part of the population believes that Europe is the enemy and has always brought the worst. This does not detract from the fact that it is a very stupid, foolish and unfounded position, but it exists. Yet, I am sure that the majority of the population wants to re-establish normal and mutually respectful relations with both Europe and America. In general, the population is tired not only of the war, but also of this constant confrontation with the entire West and Russia’s self-isolation.

The previous question was related to the idea that a population that feels strong resentment towards the West, after Putin, is likely to elect someone not very different from him.

The decisive element in my opinion will be the elections. Future elections should not be anything like what some in Russia today improperly call them. If the elections are as they are now, then not much will change and the result will be absolutely random. If, on the other hand, we talk about real elections, this means that there will probably be campaigns with different parties and candidates, with different positions, anti-European, pro-European, and others. I am certain that in a normal election, with a normal election campaign, with a verification of the election results, and I mean an honest verification, the anti-European position will not get a majority. It will, of course, be represented in parliament. But I am certain that it will not get a majority.

And do you think honest elections are possible in Russia?

In my opinion they are possible and many are talking about them in imagining the post-Putin era. I can say that we, as Memorial, have just prepared a project for the first 100 days after Putin, and on that occasion we will propose very specific measures to guide the Russian Federation in some way towards a democratic path. We will start with the organisation of elections, so that they are real elections and not pseudo-elections.

Has the death of Alexei Navalny changed anything in Russian society?

Yes, but not for the better. Navalny’s death, or rather his assassination, because it was a murder, had a negative impact on all anti-Putin democratic forces, both in Russia and abroad. For those who are still present and actively working in Russia, it was very important to know that there is a leader, Navalny, who was able to unite the entire opposition around him. He was able to unite. This hope gave strength and confidence. When a leader or a potential leader is killed, well, this disorganises, demoralises the people who were ready to fight. This has also had an impact outside Russia, because the political opposition has split into groups that accuse each other, that compete with each other. This is very sad and very damaging. If Navalny had still been alive, this probably would not have happened, or would not have happened on this scale. But that is precisely why Putin did not want to set him free. That is precisely why he was killed.

In Europe, the first steps are being taken to set up a special court to condemn the crimes committed by the regime during the invasion. Do you consider this a feasible initiative?

Although it may seem surprising, I am not entirely in favour of this hypothesis, but for purely practical reasons. Putin can only be indicted and convicted after he leaves office, which, as we know, will never happen. Extending charges to the likes of Lavrov and others will have no effect other than to make their offices eternal as well.

Many also criticise the silence of the Russian people in relation to all this. We certainly do not have to repeat the enormous difficulties that those who want to oppose it have in a dictatorship, but do you not think that the Russian people are in some way co-responsible for what their leadership is doing?

To examine the question of responsibility, I find it useful to read the book written by Karl Jaspers immediately after the war on German guilt. He basically identifies four categories of responsibility: legal, political, moral and existential. I agree with him, although this interpretation is not very popular in the Russian diaspora. Legally, there is no collective responsibility because everyone is responsible for their own actions. Even moral and existential responsibility each person has to deal with himself or with God. Political responsibility, on the other hand, is and must be collective. Those in favour of war, for example, have political responsibility. But so do those who are against it, including myself, because we have failed to stop an aggression against a neighbouring state. This means that the problems that the Russian population has because of the sanctions and those who were forced to flee are the result of our collective responsibility.

Oleg Orlov’s words give us not only the testimony of a man who experienced the brutality of power first-hand, but also the resilient and courageous face of a Russia that does not give up. At a time when propaganda attempts to suffocate memory and rewrite history, his voice reminds us that truth exists, even when it is inconvenient, and that human dignity is a value always worth fighting for.