Frodo, Themistocles, Churchill: when good wins almost by accident

My father used to tell us The Lord of the Rings in episodes during mountain hikes.

It was the summer of my eight or nine years of age when he was reading Tolkien‘s epic masterpiece for the first time. So, whenever he had finished enough chapters and felt that he had learnt enough stuff, he entertained us for hours on end along the trails, distracting us to such an extent that we did not even think of complaining of boredom or tiredness.

(My father has a prodigious memory).

At the climax of the story, when everything had to be decided and Frodo’s quest was hanging by a thread, both he and I were eager to find out how it would end.

He could contain himself, I could not.

I sneaked into the grown-ups’ room, picked up the book and jumped straight to the chapter on Mount Doom.

Those familiar with the plot of the novel, perhaps thanks to the very popular movies that came out a few years later, will remember how central the petty character of Gollum is in it. The efforts and sacrifices of the great heroes would have been for naught without the providential help of that childish, pitiful little being consumed by a purely emotional longing for the One Ring.

As an adult, I would have understood the profound Catholic and humanistic message Tolkien wanted to give his readers with this choice, but as a child, there and then, I was hurt.

Was all that great conflict between light and darkness really resolved through Gollum? Through an insignificant detail? Substantially by accident?

Greeks versus Persians… or not?

The Lord of the Rings is an epic based on fantastic events, drawing on the best of Norse, Biblical and Greek mythology. But in our collective imagination there are also epics that have been embroidered on real events.

Think of the resistance of the Greeks against the Persian invasions, which was already experienced by its protagonists as the struggle of European freedom against Asian tyranny.

It is a myth that, from the 5th century B.C. onwards, became so ingrained in our culture that it accompanied its entire development until the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A myth so effective that today the powers of Asia do not contest it, but at most reverse-engine it: from Riyadh to Beijing to Singapore, despotism is openly praised as a source of order and progress, while European-style freedom is considered a harbinger of division and decadence.

Back in the days of the Gulf Wars, the battle of Thermopylae against the Persians surprisingly became a pop culture pillar thanks to Frank Miller’s comic book about the 300 Spartans.

This, too, was made into a movie in 2007, considered one of the latest manifestos of the braggart, comradely and neocon males who want to “rid the world of mysticism and tyranny“.

A famous comedy sketch said: “If preferring 300 to Life is Beautiful means being right-wing, well, I’m right-wing too!”

Then the crisis, smartphones and Trump shaked American conservatism. But that’s another story.

Now, 300 is a comic book that is not always concerned with historical accuracy (to put it mildly), but it has one virtue in common with its source, the Histories by Herodotus of Halicarnassus: both make it very clear that the Greeks were far from convinced to risk their lives against the Persians.

The desire to ‘make Greece free and not a slave’ was by no means universal: indeed, until the last moment traitorous, opportunistic or resigned Greeks risked overwhelming those willing to resist.

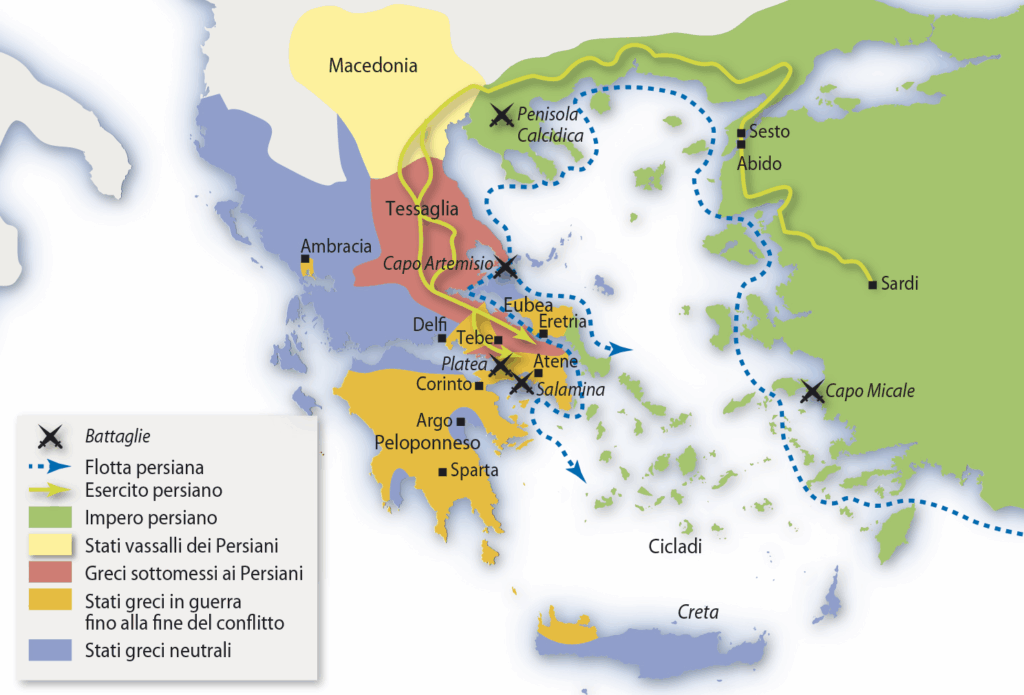

The inhabitants of the northern regions such as Macedonia and Thessaly went over to the Persians almost immediately – with the exception of the Phocians, who, however, opposed them only out of spite towards the Thessalians and certainly not for the sake of freedom.

Thebes, the archenemy of Athens, welcomed the invader with full honours, along with almost the entire surrounding region of Boeotia.

There are very few documented cases of desertion among the Ionians, i.e. the Greeks on the coast of Asia Minor who now served under the Great King.

The wiles of Themistocles

Even among the Athenians there were those who would have preferred to submit rather than suffer the devastation of the city.

When Themistocles went to consult the Oracle, the first response was a blunt invitation to flee because defeat was certain.

Themistocles had to make more generous donations to the Oracle and demand a second prophecy, which was actually slightly more accommodating: ‘The wooden walls will not give way’.

He then had to convince the citizens that ‘the wooden walls’ were the ships, and therefore that at least on the sea the Persians could be beaten. He struggled, however, because the official soothsayers of Athens were almost unanimous in rejecting this interpretation and suggesting a surrendering line.

In order to fight the first naval battle, off Euboea, Themistocles had to bribe the admirals of the other Greek fleets one by one, that if they listened to their crews they would retreat.

For the decisive battle in front of the island of Salamis, he even had to physically prevent his allies from escaping with the following stratagem: he had a fake deserter go ashore, who suggested to the Great King a night encirclement manoeuvre of the Greek fleet. The next morning, waking up surrounded, Themistocles’ recalcitrant allies were forced to fight, and thus achieved (unwillingly) the triumph of freedom over tyranny.

Having lost control of the seas, the Great King took half of his armies back to Asia, which he could no longer supply.

Themistocles took advantage of this to let him know that he had dissuaded the other Greeks from cutting off his retreat: this was untrue, but at least the barbarian tyrant would be grateful to him, and perhaps host him in Persia in case the other Athenians, whom he did not trust at all, exiled him.

Meanwhile, the other half of the Persian armies had encamped for the winter.

When operations resumed, the Athenians asked the Spartans to fight with them north of the Isthmus of Corinth to avoid a second sacking of Athens.

The Spartans, however, had worked all winter to erect a wall along the isthmus and preferred to remain safely behind it.

Furious, the Athenians threatened that they would then side with the Persians. Only then were the Spartans convinced, marched north and won (unwillingly) the final battle of Plataea.

In short, in order to save freedom it was necessary to bluff by saying that they wanted to go along with tyranny.

The Second Persian War.

From the digital materials of La Scuola Editrice

Old and new superstitions

Our high school professors taught us that Herodotus’ was not good historiography, precisely because he lost himself in these meticulous anecdotes about revenges, rivalries, double games and divine omens.

Good historiography, we were taught, was that of Thucydides, who investigated instead the ‘remote causes’ of events excluding their ‘apparent causes’: long live clashes between ‘spheres of influence’, down with anecdotes and irrational miracles.

Well, what little familiarity I have acquired with politics makes me think instead that things turned out exactly as Herodotus narrated them: an unpredictable hotchpotch of selfish calculations, psychological defects and magical superstitions, where until the very end it was not at all clear who was with Greece and who with Persia, who really wanted freedom, who wanted tyranny and who wanted neither in particular.

A trifle at the wrong time could make all the difference.

So much for the skeletal determinism of ‘spheres of influence’ and ‘remote causes’. These are perhaps as irrational superstitions as the prayers to the wind gods with which the Athenians tried to wreck Persian ships.

What to do in the darkest hour

Now, it is curious how even the second mythology that has shaped our current imagination, that of the Second World War, has simplified and romanticised a conflict in which freedom defeated oppression by a whisker and in an almost casual manner.

In the summer of 1940, there was no European nation that was not at least partly supporting the Third Reich: some with allied regimes, like Mussolini‘s, some with collaborationist regimes, like Pétain‘s, some with partition agreements, like the Soviet Union, some with free passage of troops, like Sweden, some with safekeeping of money in banks, like Switzerland.

Just Britain resisted, where, however, a not insignificant part of the government of national unity was still trying to isolate Churchill and to strike a deal with the Führer.

America, not yet wounded by Pearl Harbor, encouraged these negotiations through personalities such as the anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi ambassador Joseph Kennedy, and maintained a ban on the export of its own weapons even while London was under the bombs.

This was also the subject of a movie, The Darkest Hour (historically a little more accurate than 300), which shows a Churchill forced to tow US-made fighter jets by oxen to British Canada in order not to break the law against arms exports.

How likely was it that Britain would be able to hold out ‘until, in God’s good times, the new world with all its power and might, will step on to the rescue and the liberation of the old’?

In conclusion, is Tolkien’s fictional account of the defeat of the One Ring really so different from a historically honest account of the defeat of the Persian Empire and the defeat of the Third Reich?

Perhaps not. And that is why we should not despair when we have the impression that, in our darkest hour, we only meet traitors, opportunists, resignationists and simple undecideds: in a word, men.