Diarra ruling: how the EU Court changes FIFA rules on players’ contracts

A new shock has arrived from the halls of Luxembourg: the Court of Justice of the European Union has issued a ruling – the so-called Diarra ruling – that is destined to rewrite relations between players and clubs. And it is no exaggeration to evoke the historic Bosman ruling: we are facing a change that could mark a before and after in European football.

Just a few days before the opening of the extraordinary transfer window reserved for clubs qualified for the Club World Cup, the international union of professional footballers, FIFPRO, has unleashed a piece of news destined to echo well beyond the summer: by virtue of the recent ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Lassana Diarra case, footballers can now unilaterally terminate their contracts without fear of sporting or disciplinary sanctions. It is a legal and sporting revolution that threatens to reshape the entire ecosystem of professional football.

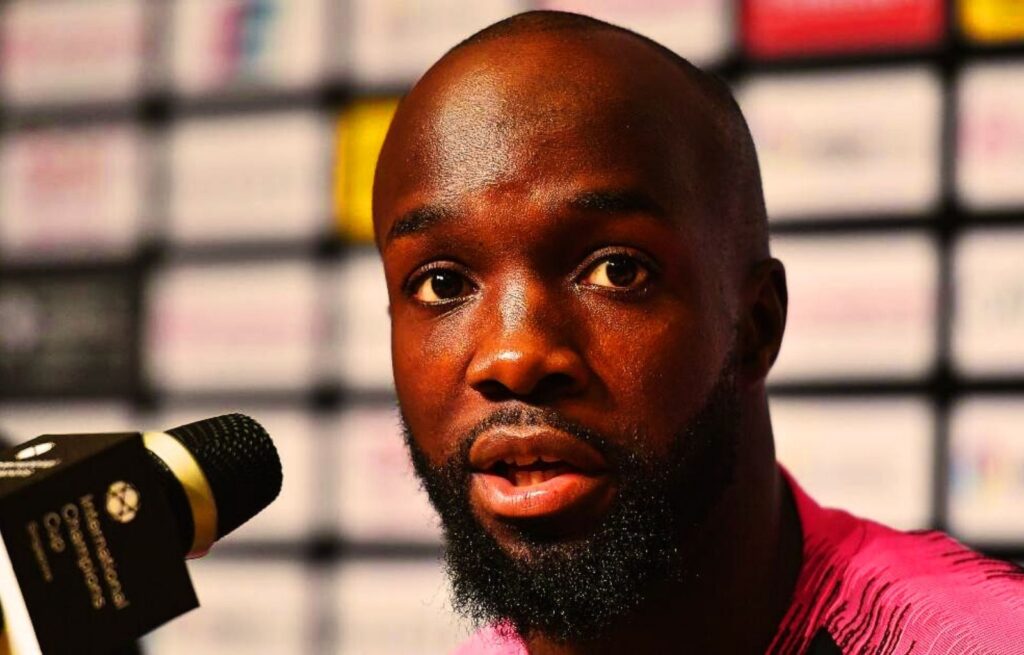

The previous Diarra: from Lokomotiv Moscow to the CJEU

The affair originated in 2014, when Lassana Diarra, then at the peak of his career, decided to break his contract with Lokomotiv Moscow due to a drastic pay cut. The club’s reaction was harsh: Diarra was disqualified and forced to sit out for months, waiting for a new signing. The former French midfielder, with the support of the French trade union UNFP and FIFPRO, decided to take the matter to the European courts.

After a long process, the EU Court of Justice agreed with him, recognising that the FIFA rules in force at the time violated the principle of free movement of workers and the foundations of European contract law. The heart of the ruling lies in a statement that is as simple as it is disruptive: there cannot be a system that asymmetrically punishes the termination of contracts by employees, when employers (i.e. clubs) retain much wider margins.

FIFPRO’s reactions and the long shadow of Bosman

In the document published in the run-up to the opening of the summer market, FIFPRO explained in detail the consequences of the Diarra ruling, clarifying that the old notion of ‘just cause’ can no longer be used to hinder the right of players to terminate their contracts. Compensation, if due, will have to be calculated according to proportionate criteria and in accordance with national law, but the principle is established: the player is a worker, not property.

The comparison with the Bosman ruling of 1995 is not only suggestive. Then, too, it was a court – and not a legislator – that intervened to break an oppressive mechanism, guaranteeing freedom of movement to released players. Today, with Diarra, the European Union reaffirms its regulatory vocation also in the world of football, not as a bureaucratic imposition, but as the application of fundamental rights.

Collective bargaining or deregulation?

FIFPRO, although aware of the disruptive scope of the ruling, reiterated that regulatory chaos is not the goal. The statement speaks clearly: a new transfer architecture based on collective bargaining is needed. In the absence of shared and negotiated rules, there is a risk that the market will only be governed by the bargaining power of the most unscrupulous agents and the richest clubs, generating new inequalities.

In the short term, it is likely to be the big stars who benefit most from this new freedom, being able to use the threat of termination to renegotiate terms or force transfers. But in the medium term, the most lasting benefits could concern the players in the lower leagues and the less protected workers in the football system, who are often victims of contractual abuses or late payments.

What changes for European football

In concrete terms, the ruling also calls into question the principle of transfer fees as an element of the player’s ‘indirect’ salary. From now on, those values can no longer be used to calculate the compensation in case of contract breakage, with a potential impact on budgets and the sustainability of market transactions.

European clubs are therefore called upon to respond lucidly to this new phase: not with corporate resistance, but with strategic intelligence. FIFA regulations, as they stand, are no longer compatible with European law. Better to come to terms with this before the courts decide – once again -.

Towards a new European model?

If European policy really wants to count in the field of professional sport as well, it cannot limit itself to the role of judge of last resort. It is time for the Union to build its own agenda for professional football, capable of combining individual freedom, contractual justice and economic sustainability. The Diarra ruling is an opportunity: to rethink, together, the future of one of the most global sports of our time.