Rising Lion and Midnight Hammer: the culmination of escalation in Israeli strategy.

In-depth foresight exclusively for L’Europeista.

In this article we try to shed light on what is happening in the Middle East with the US attack, analysing the Israeli strategy by virtue of previous foresight, one of 30 October 2023 already analysed for L’Europeista. Below we will develop the arguments discussed in an earlier foresight of 4 August 2024 by updating it in light of recent developments.

What we see materialising in Iran today is the result of a targeted strategic choice made exactly one year ago by the Israeli government in order to get out of a forced trap, a trade-off, into which the Jewish state was forced for strategic-structural reasons.

We will divide our analysis into three macro-sectors, starting with a systematic review of the foresight regarding the escalation of August 2024, which will serve as a strategic framework, analysing the legal sector secondly, and finally the strategic sector. The in-depth review concludes with reflective insights into the long to medium term.

Overview, the Iran-Israel escalation of 2024

The foresight of August 2024 was intended to anticipate the scenarios that might unfold following theelimination of Hezbollah’s top leadership in Lebanon through the use of pagers. First and foremost, however, the targeted killing of two top leaders of the Iranian imperial network – Fuad Shukr (Hezbollah) and Ismail Haniyeh (Hamas) – ushered in an escalation that broke the strategic paralysis Israel had been in since 7 October 2023, when it suffered an attack described as asymmetrical-terrorist. This type of aggression – carried out by armed civilians and devoid of legitimate targets, with the exception of a barracks – placed Israel in a communicative, operational and legal trap: on the one hand obliged to equally restore deterrence and defend itself in complex urban contexts, on the other hand exposed to international delegitimisation and reputational attrition.

The heart of the matter remains Iran’s imperial strategy, which operates through armed and asymmetrical proxies (Hamas, Hezbollah, Houthi, also known as ‘the 3 H’s’), Tehran’s de facto territorial extensions into the sovereign territories of other states. These entities militarise local populations, disarticulate institutions and act as vehicles for Iran’s indirect warfare. Israel, while excellent in counter-asymmetric operations, cannot sustain this type of warfare for long, which is costly, unpopular and demographically unsustainable.

The escalation of summer 2024 was therefore a strategically necessary choice, the implications of which are culminating now. By opening a new theatre, Israel has brought the conflict to the symmetrical and conventional plane, where it can exploit its technological, doctrinal and diplomatic superiority. In doing so, it has forced Iran out into the open, abandoning the comfort of proxies. However, Iran, unable to exploit its numerical advantage in a land confrontation as it does not border Israel, is forced to choose between:

- intensify indirect support to militias, risking loss of effectiveness and deterrence;

- respond with symbolic operations, exposing themselves to reputational attrition;

- undertake a direct confrontation for which he is not prepared.

In any scenario, the strategic advantage shifts in favour of Israel, which demonstrates that it has skilfully broken the pattern of proxy warfare. Moreover, this phase also forces international actors – particularly the Western allies – to break out of ambiguity by taking a clear stance in the face of a possible Iranian attempt to saturate the Israeli defence system (Iron Dome).

Escalation in this case is not just a legitimate defence against an irregular network, but a tactical and geopolitical manoeuvre aimed at re-establishing a more manageable and less manipulable balance. In the current context, it appears inevitable; all the more so if Israel intends to maintain the initiative, avoid reputational dissolution and break the destabilising spiral imposed by Iran through its parastatal militias.

2. International legal dimension

In recent days, the claim that first the Israeli and then the American actions were ‘totally unjustified and illegal aggression’ has taken hold. In order to understand whether this position has merit, one has to unpack the argument.

First of all, it is necessary to distinguish between the lawfulness of a military action and the fact that it is unjustified – or, more precisely, ‘unprovoked’. In fact, the lawfulness of a military intervention largely depends on the presence of a justification, such as a provocation suffered. Let us therefore start with the latter.

Meanwhile, why is provocation important in determining whether a military attack is lawful or not? Simple answer: the use of force is protected only and exclusively for defensive purposes, so provocation constitutes the pivotal element that activates the right of legitimate defence as a condicio sine qua non. Assuming, however, that the nature of international law is not covenant but natural, i.e. customary, it is nevertheless useful to clear one’s head as to what it says that comes closest to a ‘Constitution’ at the international level, i.e. the Charter of the United Nations.

In Article 2(IV), the Charter enshrines the prohibition of the use of force not only directly, but also indirectly. In fact, just as military aggression per se is prohibited, so too is the threatened use of military force, whether in the first or third person.

Verbatim:

“Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force, either against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations “*.

Two prohibitions are derived from this article, namely the prohibition of threat on the one hand and the prohibition of aggression on the other. Consequently, it can be said that international jurisprudence has also largely recognised the indirect aspect as being subject to this prohibition. This implies that not only may one not threaten or militarily attack another state, but sponsoring armed groups that do so is also prohibited.

There are several such armed groups today, all headed by Iran, including Hamas, Hezbollah and the Houthis. Responsibility for their actions legally rests with Iran, both as the instigator and as the sole legal entity. Both legally and strategically, the actions of the Iranian proxies cannot and should not be given their own autonomy, as they are directly led by Tehran.

In order to understand how the actions of the proxies (the ‘3 H’s’) fall on the principal (Iran), the ruling of the International Court of Justice in the ‘Nicaragua vs USA’ case must be analysed. In that ruling, the US was found guilty not of having attacked Nicaragua itself, but of having attacked it indirectly through sponsoring and financing armed rebel groups.

Verbatim:

“The United States, in recruiting, training, arming, equipping, financing, supplying and otherwise encouraging, supporting, aiding, and directing military and paramilitary actions in and against Nicaragua, has violated and is violating its express charter and treaty obligations to Nicaragua” **

Indeed, the International Court of Justice ruled that the United States violated the prohibition on the use of force enshrined in Article 2(IV) of the UN Charter by intervening in Nicaragua by arming, financing, equipping and supporting paramilitary groups (the so-called ‘Contras’) acting against the Nicaraguan government. The Court held that such support to paramilitary groups constituted an unlawful use of indirect force, representing an unauthorised armed intervention in foreign territory, incompatible with the purposes of the United Nations and customary international law.

Let us therefore make an outline in order to understand what constitutes unlawful conduct:

| Prohibition of threats | |

| Direct* | Indirect** |

| Prohibition of the use of force | |

| Direct* | Indirect** |

We can therefore see how all four prohibitions have been violated by Iran: direct threats have been the order of the day for decades, there is even a public screen in Tehran with a ‘countdown’ to the hoped-for destruction of Israel. Examples abound. Indirectly, the same threats are also perpetrated by Iranian proxies, again examples abound.

As for the direct use of force, one only has to think oflast summer’s attack by Iran against Israel; for the indirect use of force, one only has to look at the work of the Houthis against Tel Aviv, the Hezbollah for decades now, and last but not least the 7 October attack at the hands of Hamas.

Iran has – without exaggeration – violated all four international prohibitions on the use of force. Added to this is the aggravating factor of historical consistency: Iran has historically represented a threat to Israel – for purely ideological and racial reasons – for several decades now, and one cannot therefore frame the issue as a random spat of the moment. It is also difficult to speak of a pre-emptive strike (known as pre-emptive defence) in the strict sense, since hostilities have already been open for years. A pre-emptive strike is between two actors who are not yet at war.

Ergo: the initial claim that the Israeli attack constitutes an unprovoked aggression (unprovoked aggression) therefore borders on the demented, with no margin for opinion.

However, there is one problem: ‘causation’.

Every military action must be legitimised , and official legitimisation is what then holds up before international law and before international consensus. If so far in our discourse there has in fact been a convergence between law and strategy, here the two dimensions take different paths. In fact, while for strategy the form counts as much as a three of spades, legally the official form of a military action plays an important role.

Indeed, Israel has claimed that the attack against Iran has as its main objective the destruction of the Islamic Republic’s nuclear capability.

But Iran has no atomic weapons and there is no evidence that it is developing them. And this is legally a big deal because it echoes a precedent: the notorious Colin Powell waving fake evidence of weapons of mass destruction at the UN General Assembly to legitimise intervention in Iraq. There, too, the problem was causality.

But can a death cult like the Ayatollahs have access to the atomic weapon? Who are we to demand otherwise?

There is a universal consensus as to why the poor Ayatollah – progressive, secular and peaceful – should be banned from having atomic weapons: however, in the last few days, the vulgate has been going round according to which the ‘Niet’ behind the Iranian nuclear ban is the usual Western whim. Instead, it is useful to recall how this ban imposed on Iran is ‘bipartisan‘, in fact also shared at the UN by Russia and China. Apparently not even Iran’s friends are convinced that the possession of 400 kg of uranium enriched to 60% – when 4% is sufficient for civil nuclear energy – is only for peaceful purposes. It is also worth mentioning an opinion shared here thatIran is not bound by any form of MAD.

UNSC Resolution 2231/’15 (binding), the one being referred to, saw a unanimous vote by China, France, Russia, the UK, the USA, Angola, Chad, Chile, Jordan, Lithuania, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Spain and Venezuela. It is therefore not a Western whim.

Leaving aside therefore the substance, the form remains legally relevant, as it opens up new, legally disruptive scenarios. Indeed, a future ‘Kosovo effect’ may emerge. By this term I refer to the 1999 rupture of theOpinio iuris of state integrity as a universal principle: following this rupture there were disruptive effects in international relations. In fact,NATO’s aggression against Serbia in spring 1999 to protect the Kosovars paved the way for Russia to justify its interventions in Georgia as well as in Ukraine.

But the real question here is another: why did Israel use the justification of the nuclear weapon for its military operation?

We have seen that Iran has violated all the norms on the use of force, thus giving Israel full right to defend itself, and knowing very well the importance of giving proper causality to military operations, one wonders why Israel has chosen to take precisely the steep anti-military road as a means of legitimising its actions. Referring to all of Iran’s antecedents was already amply sufficient to fall within international lawfulness, so why want to raise the bar unnecessarily thus exposing itself to various criticisms?

Here we leave the legal field and enter the purely strategic field, specifically the mechanics of internationalisation and nationalisation of conflict.

3. Strategic Dimension

Internationalisation and nationalisation of conflicts are two dynamics inherent in relations between international actors, both state and non-state. The internationalisation of conflict refers to military, media, diplomatic and commercial measures aimed at linking one’s own specific interests to those of as many external actors as possible. Nationalising a conflict, on the other hand, is the opposite, i.e. trying to sever the interests of as many external actors as possible from the conflict.

Let us try to understand its meaning with examples. In a clash between a strong and a weak actor, the strong one will try to keep the management of the conflict to itself so as not to have to suffer outside interference that might compromise the advantage of strength; while the weaker actor, by virtue of its minority, will seek outside help and to do so will devise any means to make the third party actors believe that their interests are also at stake. They are two perpetually opposing forces and always depend on the relative balance of power.

The Kosovars in 1997, unable to win on their own against Yugoslavia, tried first with Rugova’s pacifism and then with the massacres of the KLA to draw the attention of the West to themselves so that they would intervene, thus changing the balance that was unfavourable to them. Milosevic ‘s Yugoslavia, on the other hand, always tried to play down the Kosovo issue, labelling it a ‘national question’ in order to avoid intervention by other forces. The same can be said of Zelensky who, as a weaker player than Russia, tries in every way to internationalise the conflict so as not to be overwhelmed by Moscow. When Kiev speaks of risks for the entire West linked to Russia, he is doing nothing more than linking an interest of ours to an interest of theirs. This, of course, does not detract from the veracity of the issue and the validity of the Ukrainian complaints.

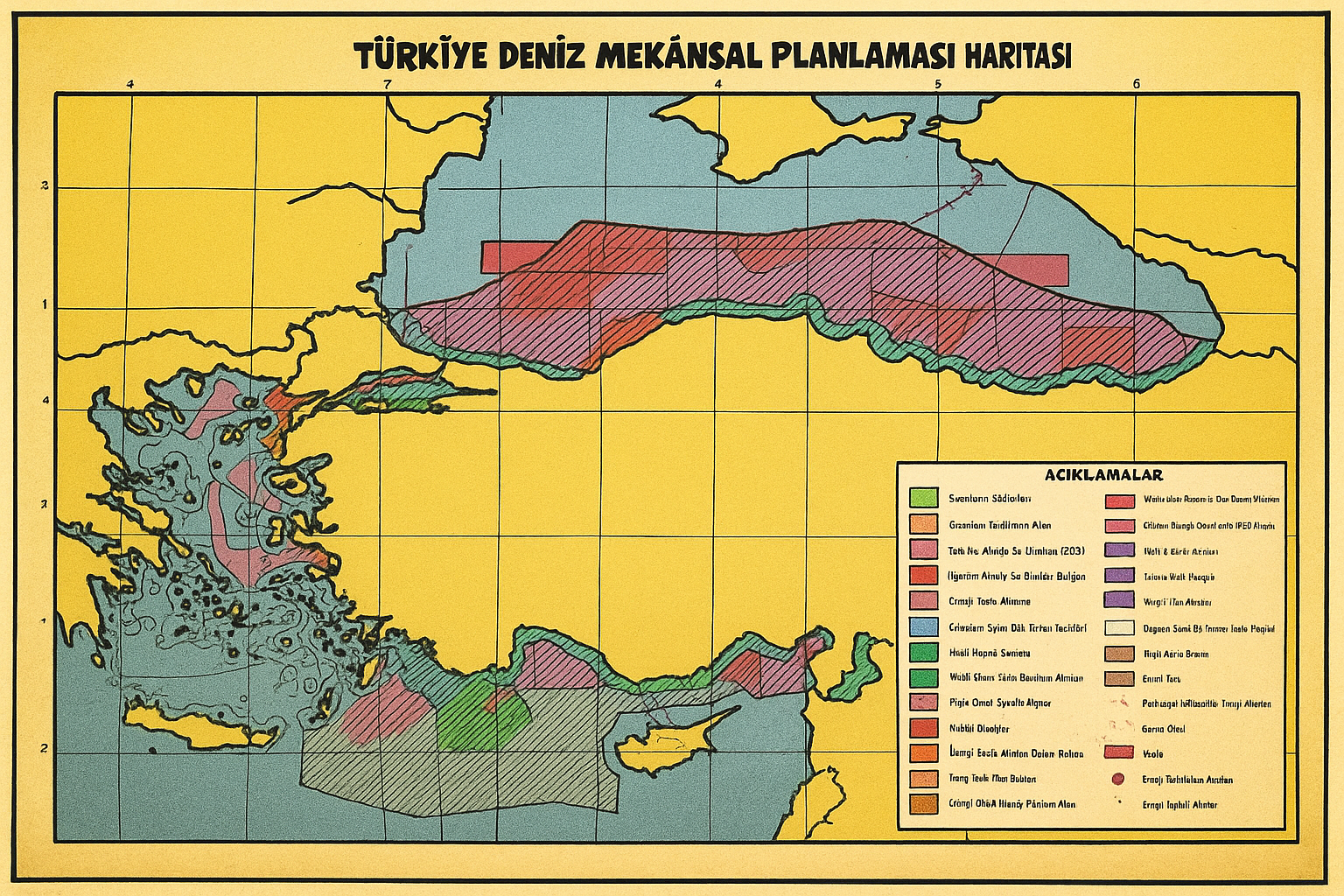

The same logic applies to Israel. The Jewish state in the Gaza issue tried (with little success) to nationalise the conflict in order to avoid external interference, but with Iran it is a different matter. Even though Iran has proved to be a giant with feet of clay, whose air defences collapsed within minutes, it is still a significant threat to Israel, unable to neutralise the strategic centres of the Islamic Republic on its own.

This is why an omni-partisan international motive has been brought up, such as nuclear armament already dealt with in the aforementioned Resolution 2231.

But in addition to being omni-partisan, such a ‘motive’ is a crucial element in the agenda of the great powers, first and foremost the USA, which unlike China and Russia, which are opposed to Iranian nuclear power, are historical allies of Israel. It can in some ways be argued that Israel imposed the conditions such that Washington was obliged to intervene. Hence, it is consequential to understand the haste with which Washington immediately sought a cease-fire: it is not immediately an American war, it is to the minimum extent that they are called upon for the reasons mentioned above.

This is where a different discourse on the lawfulness of American intervention comes into play. Formally, Iran has transgressed much less against the US than it has against Israel. Although the strategic positions of the US and Israel are similar, legally they are distinct: against Iran there is still thetort of threat against the US, but it is obviously a much weaker position than against Israel. If, therefore, on the Israeli military action there is little to interpret, on the American one a variety of counterproductive interpretations can be opened for the future.

4. Conclusions and final considerations

The year 2025 is perhaps more than any other the year of terminological inflation: between a genocide that does not exist and a misuse of the term ‘geopolitics’ to mean anything foreign-related, the word of the moment seems to be World War III. Well, let us, given the success of the previous ones, advance another foresight: there are no structural conditions for a Third World War. Perhaps the more correct term would be Cold War II, and that one has certainly already begun almost two decades ago with the 2008 crash that paved the way for ‘alternative world orders’.

World wars are the apotheosis ofthe internationalisation of conflicts as argued before and are triggered because, among other reasons, alliances act as a viral factor. The juxtaposition of alliances without effective deterrent power creates the ideal structure for the quasi-viral expansion of conflicts. To date, we have neither of the above conditions. In fact, there are no opposing alliances but only one alliance (i.e. NATO) without a counterpart; as a second factor, we have deterrence: whereas the deterrence factor was absent in the world wars, it is now largely present thanks to atomic arsenals.

The two events of historical significance that we have analysed here, Rising Lion and Midnight Hammer, are not the beginning of a third world, but are the culmination of a second cold war that seeks to redress the balance.

As components, however, of a war, albeit a cold one, they always constitute elements whose fruits could in the future lead to conflicts on a larger scale. However, as long as deterrence is not undermined and as long as no alternative military alliance to NATO emerges, the danger of a global hot war can be said to be averted for the time being.

The concrete effects in the writer’s opinion will be:

1. A greater strength of Western deterrence, valuable at a time of a sharp decline in our sphere of influence.

2. A new future indebtedness in terms of substantial changes in the international Opinio Iuris, a factor that may have boiling over effects.

3. The future of Persia: there are real doubts about the future of Iran, as the rule that has always been upheld here is confirmed for the time being, namely that any government, however oppressive, enjoys popular consensus to varying degrees. In fact, despite the tabula rasa of the Islamist leadership made by Israel, Iranian civil society is still struggling to concretely rise up and take the place of the Ayatollahs. If the opposition does not act quickly, the window of opportunity within which to overthrow the republic will close and the conflict will risk crystallising, resulting in the massacre of dissidents and collaborators.

4. If the West turns back, it will only have wasted an opportunity and annoyed the sleeping dog.

To close, given the inflation of terms, I will allow myself a banal analogy with World War II. Dmitry Medvedev recently claimed that ‘since Iran was attacked, it will now develop the atomic bomb’, implying that if one day Iran were to manufacture nuclear weapons, it would be the West‘s fault for a change. And here the analogy with World War II: are we happy with the millions of lives that World War II brought with it? If it could have been avoided, would we not all have done so? Would we not have stopped Hitler before it was too late? In words, a rational person would answer yes. But alas, this is not the case. When the situation is put in real terms, even the most fervent anti-Nazi immediately changes course.

The factor that made Hitler dominant and capable of such destruction was appeasement, Chamberlain‘s pacifism, one of the greatest plagues of the 20th century. The snake must have its head cut off before it bites, not afterwards. From the pillory one can get out, from the coffin one cannot.

If Chamberlain, instead of turning the other cheek to Hitler, had suddenly intervened today we would not have had that disastrous war. But we would not even have known there was going to be one, and even then we would have had the pacifists, fake or real, who would have denounced such wickedness towards the poor Austrian watercolour painter. Today we must absolutely avoid creating the conditions for war and then mourning the dead.

Unfortunately, this simple lesson seems not to have been learnt: history is cyclical because the belief that it is linear and unrepeatable leads us cyclically to make the same mistakes.

The insight you have read is fully endorsed by the association Students for Israel