Christ among Cain and Romulus: a work by St. Augustine to understand the new pope

In 380, the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as its official religion. Just thirty years later, the old capital, Rome, fell into the hands of the barbarians.

The event was a shock. The Christians, now accustomed to trusting in the empire and its protection, cried out for the imminent end of the world.

The heathens, still numerous among the senatorial and intellectual elite, reared their heads and pointed to the sack of Rome as a revenge of the ancient gods betrayed.

In this atmosphere of panic, St Augustine, bishop of a small town in North Africa, picked up his pen and set to work on a monumental work, in which he defended the Christian faith against the accusation that it had caused the fall of Rome and the gradual unravelling of the Empire.

Thus was born De civitate Dei (which we instinctively translate The City of God, but actually means The Statehood of God or The Society of God): the text that changed the history of Western Christianity forever, radically distinguishing it from that of every other civilisation that existed before or after it.

A text that Pope Leo – a former general of the Augustinians – knows perfectly well. Its echo has been heard in almost every public speech the pontiff has delivered so far, and perhaps it holds the keys to understanding how the Church will orient itself in the geopolitical labyrinth of the coming decades.

Rome, one earthly city as any other

In his masterpiece, Augustine did not merely point out that other empires had already collapsed while worshipping the same gods as Rome.

He did not merely point out that, in the tragedy of the barbarian invasions, the presence of the Church and the respect it commanded had saved thousands of lives.

He did not limit himself to arguing that in all probability the heathen gods did not even exist, compiling a tasty review of philosophical quotes on the internal contradictions of polytheism and historical sources on the invention of polytheism as a tool to subjugate the ignorant.

Augustine did much more: he directly grasped the nettle and asserted that the fall of Rome was not in itself something to be regretted.

For the Roman Empire, like any other human institution, belonged to the civitas terrena, which is only a failed imitation, if not a perversion, of the civitas Dei.

“Two loves built two cities,” wrote the African saint: “the love of self driven to the point of contempt of God built the earthly city, the love of God driven to the point of contempt of self built the heavenly city”.

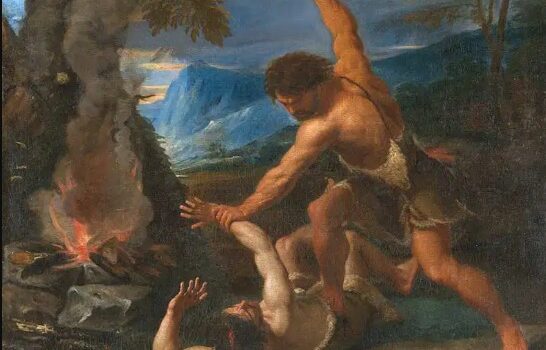

In the Holy Scriptures he read that Cain founded the first earthly city immediately after murdering his brother Abel(Genesis 4:17). He then deduced that from Abel the heavenly city was born, at the moment when, by dying innocent, he had prefigured Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross.

Since then, both statehoods aspire to gather men into them, but in two opposite ways.

The citizens of the heavenly statehood are held together by the gift of self that Jesus Christ made, and they have no glory except in God.

In contrast, the citizens of earthly statehoods are held together by their rulers’ thirst for power, and Rome, also founded by Romulus through the murder of his brother, was no exception. ‘In order that one alone might hold all power, his companion was eliminated’.

In the case of Cain, furthermore, the lust for power was not even necessary: all that was needed was “that devilish envy which the wicked bring to the good, based solely on the fact that one is wicked and the other good”.

A tragic and evil-conscious Enlightenment

The civitas Dei, however, will only show itself in its splendour at the end of time. For the duration of world history, it will remain a “stranger”, a “pilgrim” or even a “slave” of the civitas terrena, the only visible and triumphant one.

That is why, in the history of human kingdoms, we never see authentic peace, which would be God’s peace, but only a fiction of peace, a peace “that must be achieved through wars”, with “victories that are either mournful or are in any case short-lived”.

We never see authentic justice, which would be God’s, but only a fiction of justice, which, in order to find a guilty party, does not hesitate to torture the accused and even witnesses, “inflicting a certain punishment for an uncertain crime”.

We never see authentic wisdom, which is that of God, but a clash of philosophical theories that are impossible to reconcile, or, even worse, the deceptions of astrology (which Augustine in his book unmasked with an abundance of evidence).

In short, political power is incapable of saving souls and it would be absurd to ask it to do so.

Regarding religion, it can make, at best, an instrumental and calculated use of it: as Augustine states, ‘The good use the world to enjoy God, while the wicked use God to enjoy the world’.

Mind you, these beliefs did not make Augustine an anarchist. He still thought that the state was a lesser evil than disorder, that the Roman state was a lesser evil than the barbarian ones, and that the Christian Roman state was superior to the idolatrous one.

They did not make him a liberal either: he would have been horrified by a society in which ‘laws concern only what may harm the other’s vineyard, and not what may harm one’s own vineyard’.

To attempt to forcibly modernise his thinking, in any sense, is ridiculous.

Yet, one can sense that his masterpiece was the source of the most extraordinary turning point in Western history: the medieval separation between sacerdotium and imperium, i.e. between divine service and earthly authority.

From this, in the centuries that followed, sprang the shrine’s continuous struggles to make itself autonomous from the throne (as in the Investiture Conflict or the English Revolution), the throne’s continuous pushes to free itself from the shrine (as under the Swabian emperors, in the Italian Communes or in seventeenth-century monarchies with subjects of several confessions) and the resistance to attempts to sacralise the throne again on artificial shrines (such as those introduced by the Jacobins, the Soviets and the Nazis).

That none of the ‘western’ freedoms would have been imaginable without freedom of religious worship is, I believe, an undeniable fact.

The De Civitate Dei is therefore the great manual of the Enlightenment, if we do not have in mind an Enlightenment in wigwams, foolishly optimistic and insensitive to mystery like the French Enlightenment of the 18th century, but rather a profound and tragic Enlightenment, which feels evil as real and inseparable from man, but precisely because of this places its ultimate hopes in God and can therefore criticise human institutions, distorted processes, worldly glory, superstition, magic and religion bent as an instrument of government on a broad scale.

How much of Augustine is there in Pope Leo?

Let us now come to current events: what has filtered through from all this in the first statements known to us by the Augustinian pope?

Already the motto he chose is a programme: ‘In illo Uno unum‘, ‘In Him who is One we are one’.

Meaning: we are not one in the charismatic leader of a neo-imperial ethnic movement, like Donald Trump’s MAGA.

We are not one in a party that has cannibalised traditional religion and claims to control the virtue of every single subject, like Xi Jinping‘s Communist party.

We are not ‘one’ in them, but in Jesus Christ, who has a way of ‘making us one’ that is diametrically opposed to the Romulus and Cains of today.

Even his speech three years ago on the invasion of Ukraine shows an all-Augustinian awareness of the existence of a radical evil that is an end in itself.

‘So many analyses are made,’ he had said, ‘but from my point of view this is a genuine imperialist invasion in which Russia wants to conquer territory for reasons of power and to gain advantages for itself.

There is the fratricidal impulse of Romulus, then, but also the more subtle one of Cain: ‘The great historical and cultural value’ of Ukraine was, in Robert Prevost’s eyes, as much a threat to Putin as the country’s ‘strategic position’ and ‘level of production’.

The new pope also used harsh tones against disinformation, which is nothing other than the return in our age of that magical thinking that Augustine had striven so hard to defeat.

He promised to deal with how to spread critical thinking and how to handle Artificial Intelligences (which, we might say Augustineanly, risk being perceived as omnipotent neo-pagan oracles).

He called for the release of journalists imprisoned under dictatorships, just as his alter ego in the White House was savagely cutting funding for the independent press in those same countries.

And yet he has always refused, with an impressive systematicity, to reduce the role of the Church to fixing the distortions of civitas terrena, as Francis’ rhetoric unfortunately seemed to do.

In his first greeting to the faithful he repeated Francis’ key words, ‘peace’ and ‘bridges’ above all. But he also reiterated, since he was speaking to Catholic faithful, that true peace is that of the Risen One and that He is the true bridge between humanity and God.

A few hours after asking for the release of the journalists, he met with the leaders of the Eastern Churches and launched into a moving eulogy of their liturgies: “How important it is to rediscover, even in the Christian West, the sense of the primacy of God, the value of incessant intercession, penance, fasting, weeping for one’s own sins and those of all humanity, so typical of Eastern spiritualities!”

In short, it is fine to turn churches into “field hospitals” as Francis proclaimed, but without ever forgetting that Christians down here are strangers and pilgrims, who “use the world to enjoy God”.

The ‘outgoing church’ is fine, but without neglecting Augustine’s invitation: ‘Return to yourself, the truth dwells in the intimacy of man’.