Art for power’s sake: Gergiev and normalised propaganda in Naples region

The Reggia di Caserta, one of the most symbolic places of Italian beauty and history, is hosting this summer Un’Estate da RE, a music festival promoted by Campania, the region of Naples. Among the international names on the podium is Valery Gergiev, the Russian conductor known not only for his musical prowess, but for his close ties – public and political – with Vladimir Putin.

The decision to invite Gergiev has caused an avalanche of controversy, not only for his figure, but for the way in which the entire operation was supported with public funds, including European ones.

The controversy is all the more serious because it touches on an institutional issue: can we really use resources from the Italian regions to accredit on the European cultural scene a man who for years has been one of the Kremlin’s propaganda tools?

A conductor in the service of the regime

Gergiev is not just an artist. He is an ambassador. Not of art, unfortunately, but of the Kremlin’s imperial policy.

He has openly supported the invasion of Crimea, conducted concerts in the occupied territories as a symbolic gesture of legitimisation, appeared alongside Putin at patriotic rallies.

It is no coincidence that after 2022, many Western theatres – from Vienna to Milan, Munich to New York – broke off all cooperation with him, unsuccessfully asking him to distance himself from the war.

And instead, in July 2025, we find him in Caserta, welcomed with all honours. With public funds. And with the political support of the President of the Campania Region, Vincenzo De Luca.

Pina Picierno’s criticism: it’s not just an artistic question

Gergiev’s presence provoked harsh reactions, including that of Pina Picierno, Vice-President of the European Parliament. It was not a symbolic gesture, stressed the MEP, but a serious choice, which undermines the founding values of the Union: “European funds cannot be used to finance the performance of a Kremlin supporter. It is a disgrace’. But above all, Picierno pointed out, there is a deeper problem, cultural and political at the same time: ‘There are those who, after three and a half years of war, have still not understood that lending their side to Putin’s regime represents a legitimisation of its abject imperialism’.

His appeal, addressed both to the region and to the festival organisers, was explicit: remove Gergiev from the programme, to prevent taxpayers’ money – and even more, European Union money – from ending up funding those who have sided, publicly and consistently, with an aggressive and criminal regime. Picierno’s position is not an exception, but a line of principle: culture cannot be used to wash the conscience of regimes, nor to anaesthetise European public opinion in the face of the brutality of war.

Pevchikh and international denunciation

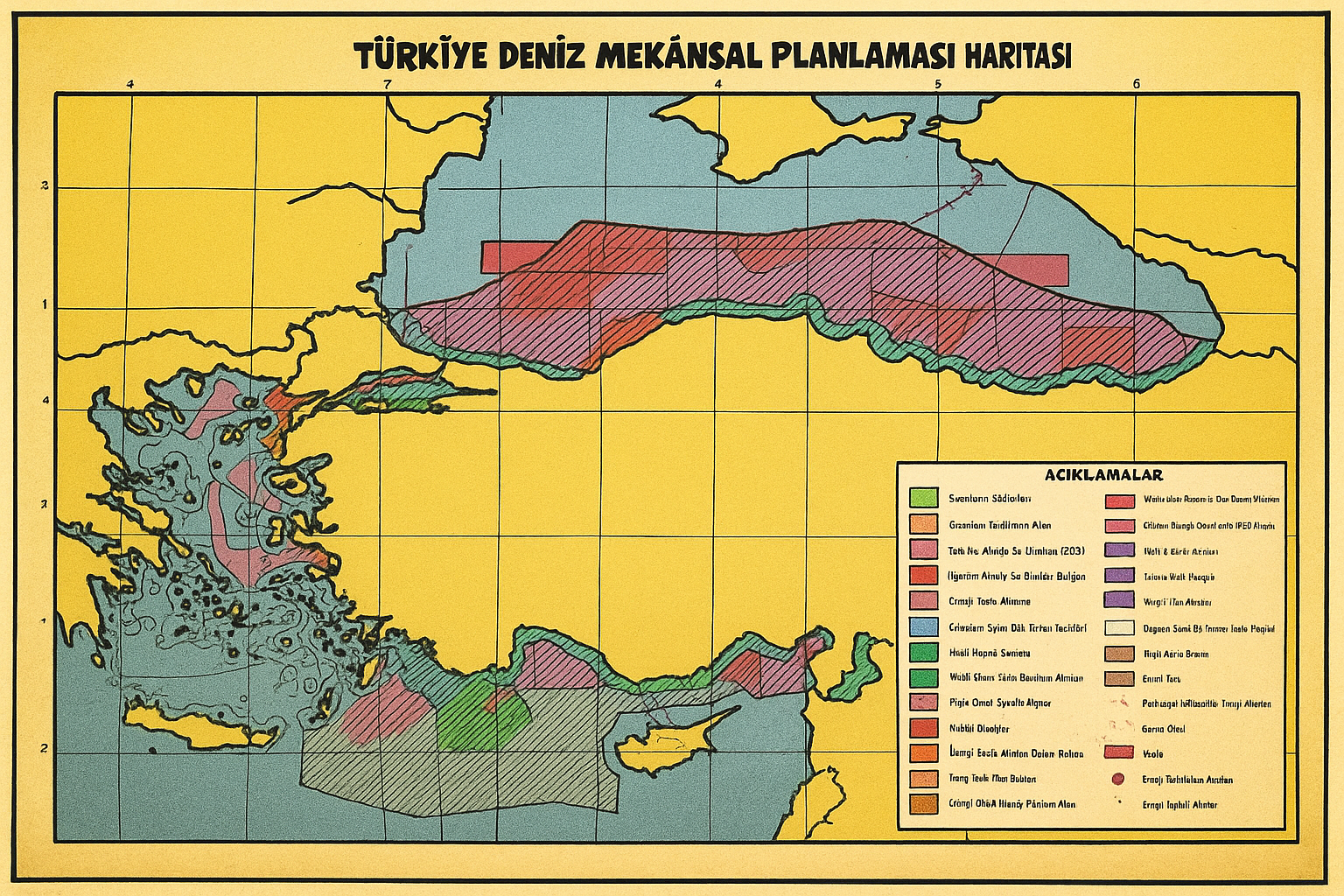

Maria Pevchikh, president of the Anti-Corruption Foundation founded by Alexei Navalny, also commented on the affair with concern. In a post on X, she drew attention to President De Luca’s political profile, recalling how in a video published in early 2024 – thus not in direct response to the controversy over Gergiev – the governor of Campania illustrated ‘the real reasons’ for the invasion of Ukraine, showing a map of the alleged ‘NATO expansion’ and echoing Kremlin propaganda word for word.

The publication of that video, which was also relaunched on the region’s official channels, gives one pause for thought. There is a worldview that relativises Russian aggression and delegitimises the West; Pevchikh writes: “Word for word, straight from Putin’s playbook. He’ll be pleased.”

The issue is institutional, not just cultural

In Campania – as elsewhere – one can and must programme culture at an international level. But to do so using public money to invite an artist who is a spokesperson for the Russian regime is to send a very risky message: war no longer matters, support for a dictator is not a problem, everything is absolved in the name of music.

And this, at a time when Ukraine continues to bury its dead under Russian bombs, is an insult. Not least because the Campania Region has a sad history of opening its channels to toxic narratives: suffice it to recall the emphasis with which, during the pandemic, content in favour of the Sputnik vaccine was promoted, despite the fact that it lacked European scientific validation. Today we risk doing the same with the Kremlin’s cultural propaganda.

A dangerous normalisation

What is happening in Caserta is a symptom of a deeper process: the slow and insidious normalisation of Russian propaganda in European institutional contexts. It is no longer just a matter of disinformation campaigns on social media or of influencers close to the Kremlin. When a regional president defends – directly or indirectly – an artist who has legitimised the military annexation of sovereign territories, we are facing something more dangerous: the erosion of Europe’s moral compass.

Freedom of expression does not mean indifference to responsibility. And culture cannot become the Trojan horse of authoritarianism. The open society is open to as many different and possibly conflicting ideas and ideals as possible. On pain of self-dissolution, the open society is closed to the intolerant and violent.

We cannot afford to be blind

Inviting Gergiev today is not a neutral act. It is a declaration. It is a choice that tells which side one chooses to be on, even when one pretends not to choose.

And if Europe wants to continue to define itself as an area of freedom, dignity and justice, it must demand that the use of its funds is consistent with those values.

Silence, in this case, would be complicity.

De Luca can go on talking about peace, openness, dialogue between cultures. But at a time when democracy is under attack by the world’s worst illiberal regimes, even a festival can become a battleground. And those who finance, programme or defend are never out of the game: they are part of the history being written. Even between the columns of a Baroque palace.