21 years ago Slovenia in the EU, today GO!2025 Rodolfo Ziberna speaks

On 1 May 2004, Slovenia officially joined the European Union. On 21 December 2007 it would also enter the Schengen Area, leaving behind sixty years of border crossings.

The great eastward enlargement of the EU, which included the Balkan nation along with nine other countries, represented a historic opportunity to dissolve ‘the iron curtain dropped on Europe’ after World War II. A process not without its pitfalls and difficulties.

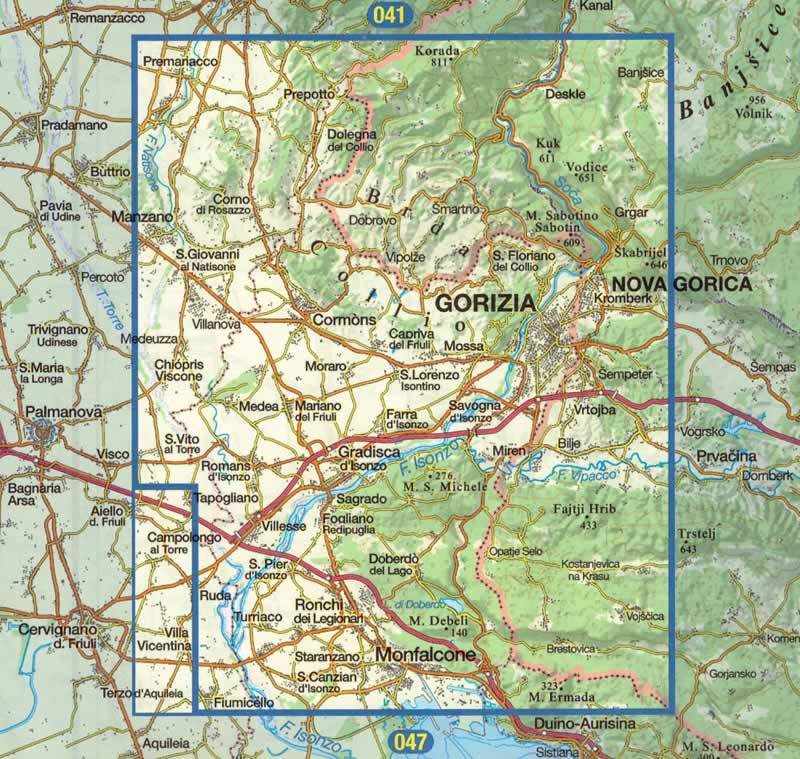

The symbol of this reunification was the city of Gorizia, located on the slopes of the Karst plateau. With the Treaty of Paris in 1947, the Isonzo area and the town of Gorizia were severed. Divided by the border with Yugoslavia then ruled by Josip Broz Tito.

Next to Gorizia a Yugoslavian ‘twin city’ , Nova Gorica, arose. The two centres remained separated for years by an ultra-militarised fence, plastically visible in today’s Transalpina-Trg Evrope Square. In 2025, the two cities are together European Capital of Culture.

To better understand the practical effects of the European integration process and the path that led to the common synergy, we interviewed Rodolfo Ziberna, mayor of Gorizia since 2017.

Gorizia and Nova Gorica. National peripheries at the centre of Europe.

21 years ago, Slovenia joined the EU, and Gorizia could re-embrace Nova Gorica. As a Gorizian, what memories do you have of those days? And how strong was the desire for Europe on the part of the Slovenians and how strong the desire for reunion with their neighbours on the part of the Gorizians?

We Gorizians, before 2004, have memories of 1991, when there was the civil war that allowed Slovenia to break away from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Those were devastating moments. Even if only for a short time, from our town we saw tank armies doing battle every day just a few steps from our borders. After independence, Slovenia’s race towards the European Union began. A choice seen by all as natural, given the territory’s historical belonging to the Hapsburg-rooted and CatholicMitteleuropa.

For us, it meant reuniting with a territory separated by war, and we were always thrilled about that. The height of my and my fellow citizens’ exhilaration came three years later, with Slovenia’s entry into theSchengen Area, when we were finally able to cross and recross the former border without any more restrictions; especially mindful of the pre-1991 restrictions with the massively militarised border stations by officers with the red star on their caps.

Therefore, we all cheered for Slovenia in Europe and, at the moment of enlargement, we uncorked the good bottle (of course, Collio Goriziano…) knowing that it would represent a year zero for Gorizia. After years as an emporium city with a trade surplus vis-à-vis Yugoslavia, we had to think again, through a new approach to the single market.

You touched on two important aspects of our discourse. On the one hand the symbolism of the Transalpine Square curtain, and on the other the economic challenge of harmonising the two territories in a context of free trade and free movement.

Let us start from that iconic place, Transalpine Square. United today geographically but not toponymically, as it is called Tver Evrope in Slovenia. While in my opinion this distinction should be maintained, contrary to the opinion of many, in order to arouse curiosity and attention to its history, the significance of this square, divided by a fence until a few years ago, is striking. Until 2007, it represented a place not frequented by the people of Gorizia, because it was a bottomless street interrupted by the border, through which people could see each other and turn their backs. Today, however, it is an open and traversable square, and embodies the European spirit.

Coming to the economic aspects, both the communities of Gorizia and Nova Gorica had to cope with the change from ‘border’ economies to market economies, a historically complicated phenomenon.

The disappearance of the border has caused chains of companies, professions and even manufacturing to collapse. A striking example is that of the SDAG, an intermodal logistics platform designed in the 20th century to provide services for the cross-border transport of goods. Without the border, the usefulness of this as well as a thousand other structures, which risked becoming ‘cathedrals in the desert’, was zeroed out. We had toreconvert the logistical platforms, no longer facing a scenario of demarcation but one of commercial openness. I cannot hide the fact that it was a trauma, especially for an area accustomed since the birth of Aquileia to being a place of transit for people and goods.

Also not to be underestimated in the analysis are the effects of the desertification of the barracks, sacrosanct, following the Fall of the Berlin Wall, which caused a major demographic decline and an economic contraction for the industry in Friuli Venezia Giulia and our province, the threshold of Italy during the Cold War.

The small territory of Gorizia, throughout the 20th century, has undergone a succession of traumas, and the watchword has always been to reinvent ourselves, and today we have the opportunity to reinvent ourselves with Nova Gorica as a unique territory, adding our potential by transforming our marginality in the respective nations into a continental centrality, also thanks to the nodal position of our territory.

We want to be a laboratory for cross-border training, showing how economic opportunities can be generated and investments attracted from a broken border. All the companies that come to us have a truly European employment and strategic approach, drawing from both countries.

The key to new development, also in the light of GO!2025, is the European process. According to you, who have a privileged view as mayor, what opinion do the citizens of Gorizia and Novigrad have of the EU after having experienced the integration process with their own eyes?

The discourse that can be made is broad. In general people, particularly Italians, have a certain distrust of novelties, and the European Union was a great novelty. In my opinion, the message has been miscommunicated, making the EU pass only as an over-regulating entity, which it is a bit, rather than as a political entity potentially a vector of development and wealth.

The very candidature of Gorizia and Nova Gorica as European Capitals of Culture was received very coldly by both citizens, due to the mistaken belief that this initiative would have drained resources previously earmarked for economic development in order to allocate them to futile cultural expenditure. This is not the case, in fact the precious European funds, which in recent years have contributed to Slovenia‘s upturn in the first place, have been spent to turn a light on our territory. Little by little, citizens are absorbing the European message, only after they have felt the opportunities and richness of our continental, non-fractional dimension. Among many, the breaking down of this prejudice is in my opinion a great merit of the GO!2025 initiative.

In conclusion, how is the year of GO!2025 going, what significant events will animate the two cities and what message is given to the current and past Frontiers of Europe?

Make yourself comfortable, and let’s start listing… Joking aside, the cities are packed with tourists and visitors. In every corner of the cities you can breathe GO!25. The Giuseppe Ungaretti and the Andy Warhol exhibition, which have welcomed more than 45,000 visitors, will be open until 4 May, and artistic, historical, choreographic, sporting and food and wine activities are proliferating every week. From the Giro d’Italia next 24 May to the big concerts in June and July and Gusti di Frontiera in October, the two cities are experiencing and will continue to experience a splendid and busy year. There are far too many activities, so I invite everyone to visit the GO!2025 website for a more general overview.

With regard to the economic spin-off, I will give two simple examples: for just one of the four concerts of those that we will be realising at the Duca d’Aosta Airport, the net return is more than 25 million euros, while in the case of the exhibitions the ratio is 1/16, for every million invested sixteen come in. All of Friuli Venezia Giulia and the entire Slovenian region of Goriška will benefit from these revenues. The message to the other borders of Europe is clear: let us get rid of our inability to get to know others and discover new horizons… and then, of culture we eat, and drink, and how!