The Catholic rite for Thomas Becket returns to Canterbury. Rediscovery of a hero

The notes of the Salve Regina, accompanied by the organ, soared towards the dizzying Gothic arches of Canterbury Cathedral on the evening of 7 July.

It is rare to see a Catholic liturgy celebrated in the landmark building of the Anglican Reformation, but this time it was worth of it.

Taking advantage of the Jubilee, in fact, a ceremony was repeated for the first time in almost half a millennium that the English were once fond of: the translation of Thomas Becket’s body from the underground crypt to an altar in the cathedral, where it was offered for popular veneration.

This tradition had been abruptly interrupted by King Henry VIII, who, after breaking away from the church of Rome, had even ordered the destruction of the altar as part of a large-scale attack against the cult of saints.

Of all the saints, then, Becket, murdered in 1170 on the orders of a king to whom he had refused to bow, was particularly inconvenient.

In more recent times, Anglicans have again begun to commemorate Becket among their saints (although they do not venerate his relics or invoke his name as Catholics do). Finally, relations between Anglicans and Catholics have relaxed to such an extent that it was possible to make the beautiful gesture of brotherhood on 7 July.

After all, Becket is not just a Catholic martyr, nor is he just an English national hero, but he is a personality who changed the course of the whole of European history by sacrificing himself for what Europeans hold most dear: freedom of conscience in the face of abuse of power.

A champion of church independence

Born in 1118, Becket was chosen at mid-century as Lord Chancellor by the young King Henry II.

It was a time when the ruling houses of Europe were trying to limit the power of the feudal lords and gain effective control over their territory, and England, like all the political creations of the Normans, was quite advanced in this respect.

Expert in jurisprudence and loyal to his sovereign, Becket helped him in this process.

It was, however, also the period of the Gregorian Reformation, by which the church had aspired to greater purity of morals and a stricter fidelity to the gospel: in order to be able to impose them, it had to give itself a hierarchical and centralised organisation that in a short time had made it almost independent of earthly monarchs, indeed often able to influence their destinies.

(The armed pilgrimages, first to Spain and then to the Holy Land, which today we call ‘crusades’ were born precisely out of an attempt to impose a rudimentary religious discipline on the class of feudal knights).

Thus, when in 1162 Henry II proposed to Becket to become Archbishop of Canterbury, in the hope that his faithful friend would tame the English clergy for him, Becket suddenly changed his mind.

From then on, his duty was no longer to serve the throne, but to serve the shrine. And with the same determination with which he had been King Henry’s right-hand man until the day before, he began to oppose his every single claim.

He did not do this fanatically, nor without reason. When Henry demanded that clerics accused of a crime should be tried according to ‘the customs of the realm’, i.e. by secular courts, Becket opposed him on the merits on some points of those ‘customs’, not on the general principle.

However, when Henry, with the Clarendon Constitutions, claimed to have the final say on the appointment of bishops, i.e. to turn the church into an instrument of the monarch to control the religious conscience of his subjects, Becket refused to sign and was sent into exile.

Murder

Becket sought the support of the pope, but times were hard for Alexander III Bandinelli: the struggle for bishop appointments had entered his house along with the armies of Frederick Barbarossa, war raged between the German emperor and the Italian city councils, and the friendship of other European capitals, starting with London, was indispensable to him.

So Becket had to compromise with the king and return to England as a loser.

The folk enthusiasm for his return, however, was immense. When Henry, in order to belittle him, had his son’s coronation celebrated by another priest, Becket denounced in a sermon all the priests and barons who had taken part in this outrage, arousing the indignation of the crowd.

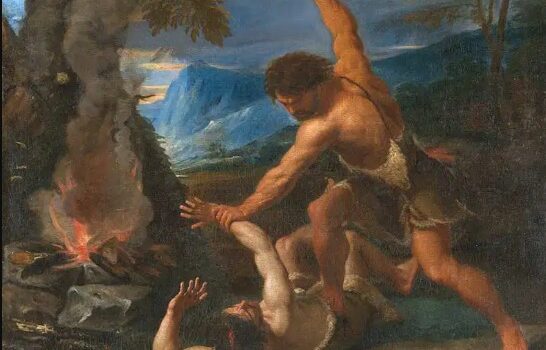

At that point, Henry, according to legend, uttered the words : “Who will rid me of these turbulent priests?”

And four knights of his court, whose first and last names we know, followed Becket to the cathedral where he was going to sing Vespers and there murdered him in cold blood.

From history to myth

As often happens, the emotion for the dead one was as great as the distrust for the living one.

Alexander III made him a saint in record time (1173, three years after his murder). As for King Henry, weakened in the face of his internal enemies, he had to do penance at the martyr’s grave with his head sprinkled with ashes.

A generation later, his son John Lackland found himself in an even more precarious situation after an ugly defeat against the French, and had to surrender to all the demands for autonomy that came from his subjects, starting of course with the church.

In the Magna Charta Libertatum, which John signed in 1215, the first principle to be affirmed was precisely the freedom of the church, followed by the right of every free subject to be judged by a court of his peers in a fair trial, and the right for parliaments to pronounce on the king’s fiscal choices.

It was the dawn of the modern world. And the memory of Thomas Becket, revived each year by the ceremony of the translation of his body to the very place where he had been killed, had helped to bring it to life.

Among young Britons, ‘papism’ is no longer taboo

Becket’s courage is the heritage of all Europeans, including secularised and atheistic ones. And the United Kingdom has been one of the countries where the decline in religiosity has been most marked in recent decades.

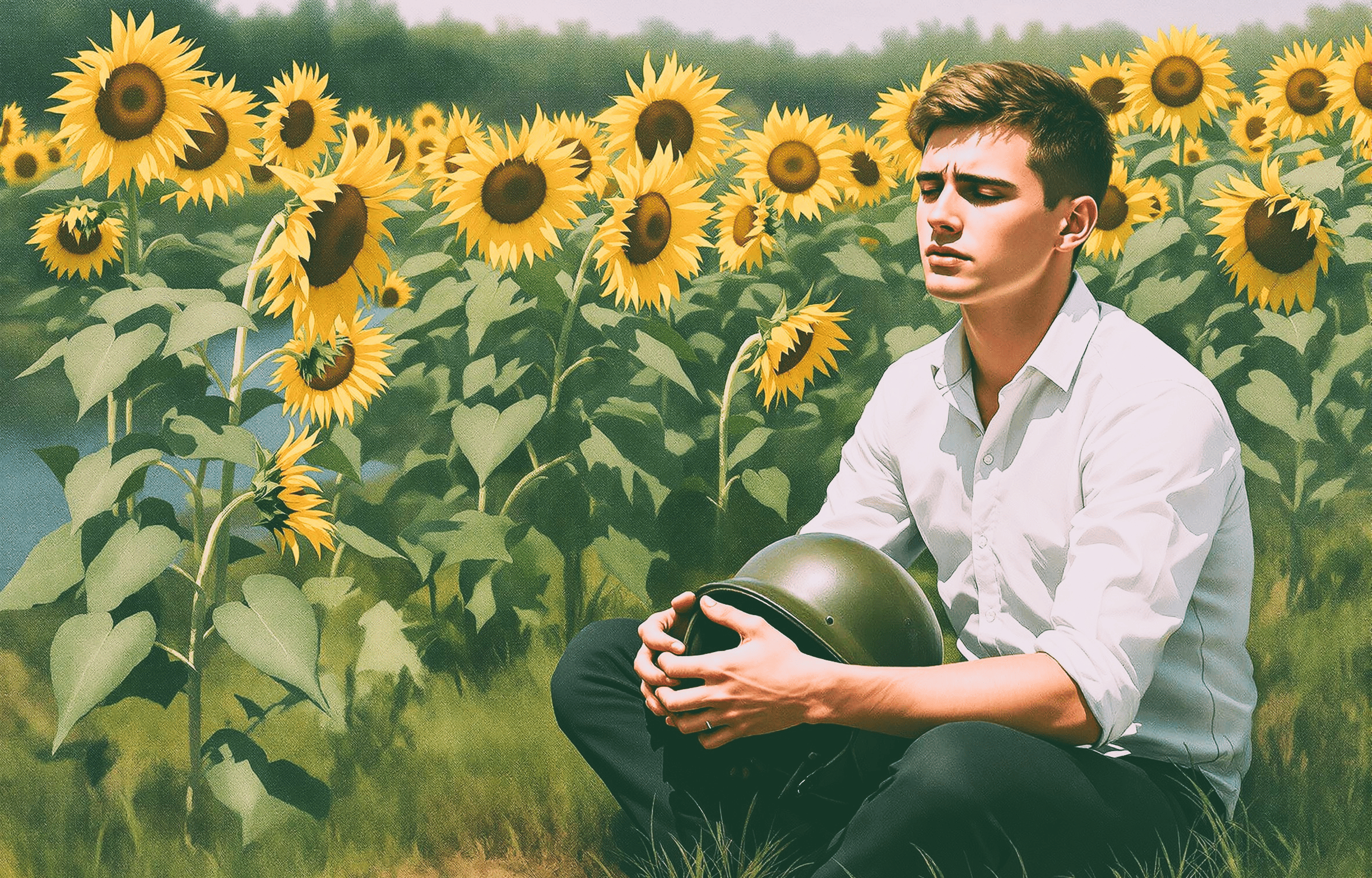

However, recently there has been a small flare-up among 18-24 year olds: compared to before the pandemic, those who call themselves Christians have risen from 6% to 18% (22% among males) and Catholicism has become by far the preferred choice (41%, twice as many as Anglicans and Pentecostals).

We can discuss at length how and why: more frequent migratory background, more traditional and evocative liturgy, stronger involvement in charities, imagery more suited to the age of social media.

But it is a sign that perhaps, under the ashes of contemporary society, something is moving, old wounds are being healed and old taboos are being overcome. In a kingdom that has a Muslim as mayor of the capital and recently had a Hindu as prime minister, a grand return of the ‘papists’ is less shocking than it would have seemed to our grandparents.

Una in diversitate, says the motto of Europe, in the language of Becket and the medieval clergy.