The crisis of the Trump method. From dealer maker to retreating spectator

The two-hour phone call between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin on Monday is one of those events that, more than for its concrete results, stands out for its symbolic weight. There were no steps forward, and perhaps not even any sideways steps. In fact, in some ways, there has been a turnaround. Trump, who in the election campaign promised to end the war in 24 hours, is now threatening to withdraw from the negotiations within a month if there are no visible results. It is a drastic communicative evolution: from ‘deal maker’ to ‘deal quitter’. And as is often the case with Trump, the media narrative is as valuable as – or more so – than the actual content.

Russia, for its part, continues to play out a script it has already seen: willingness to dialogue in words, intransigence and threats in deeds. Putin is not backing down. On the contrary, the tone of the Russian negotiators in Istanbul, where parallel talks were held with the Ukrainian delegation, was more reminiscent of a medieval ultimatum than an attempt at a diplomatic solution.

The dynamics evidenced by the conversations at several levels – Washington, Moscow, Kiev, Brussels, the Vatican – clearly show how the war in Ukraine is now also a matter of international communication. And in this communication, the US, Russia and Ukraine are playing different games with incompatible rules.

Above all, Trump, who has always conceived diplomacy as an extension of his communicative strategy, now finds himself caught between two fires: on the one hand, the need to keep control of the narrative – and of his own image as a fixer – and on the other hand, the evidence that neither Russia nor Ukraine are moving according to the timing and logic of American electoral communication.

Moreover, this phone call falls at a delicate moment for the so-called‘Trump method‘: a doctrine of international relations based on muscular bilateralism, economic leverage (tariffs) and systematic marginalisation of the European Union. It is a strategy that, in contexts of widespread instability, may appear effective. But at the test of real war, it shows the first cracks.

The Trump method: from mediator to spectator

From day one of his second term, Trump set the Ukrainian conflict as a muscle test for his international leadership. He promised swift peace, authoritative mediation, and a solution that would bring both Moscow and Kiev into line. But as the months have passed, that narrative has deflated under the weight of reality: Russia is not willing to negotiate from a position of equality and Ukraine is not willing to cede territory in exchange for promises.

The communicative change is evident: from triumphalist tone to conditional tone. “I will back down,” Trump said. A statement that not only represents personal frustration, but also a pre-emptive strategy of de-accountability: if peace is not achieved, it is not his fault. It is a fail-safe narrative.

The original proposal for a 30-day ceasefire, negotiated in Jeddah with the support of France, Germany, the UK and Poland, was completely abandoned. Moscow reversed the terms: first negotiations, then truce. In other words: first diplomatic humiliation, then perhaps suspension of the bombing.

Trump has also hinted that he will not impose new sanctions, arguing that they would be counterproductive. He even hinted at ‘business opportunities’ with post-war Russia, a statement that tears away the residual veil on any form of deterrence. The US president is talking as if Ukraine is already a footnote in the new post-conflict economic entente.

The Vatican, evoked as a possible venue for negotiations, fully fits the Trumpian narrative: a ‘neutral’, symbolic, authoritative but not incisive venue. An ideal stage for theatrical diplomacy, but little functional for the concrete resolution of an ongoing conflict.

Within this framework, Trump continues to communicate rather than negotiate. His doctrine – a kind of ‘media realpolitik ‘ – is based on building a favourable public perception. Not so much on the achievement of actual results as on their spectacular representation.

The language of war and the cynicism of negotiation

The real crux of the matter is not so much American diplomacy as Russian posture. The Istanbul talks, presented as an opportunity for a revival of dialogue, have turned into a lesson in strategic intimidation. The statements by Vladimir Medinsky, the head of the Russian negotiators, are among the harshest in recent months.

“We can fight one year, two, three. We fought in Sweden for twenty-one years. We are ready to fight forever’. The sentence was addressed directly to the Ukrainian delegation, and perhaps in particular to Serhiy Kyslytsya, former UN ambassador and uncle of a soldier killed in 2022. An emotionally calibrated communication to hurt, not to persuade.

Moscow formally demanded the cession of four regions: Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson. Some are under partial control. But Medinsky upped the ante: if Kiev does not give in now, ‘next time we will talk about six regions’. A clear threat: Kharkiv and Sumy are next on the list.

Russian diplomacy is an extension of the battlefield, not an alternative to it. In this, Putin is consistent with his historicising rhetoric. The reference to the Great Northern War, which ended in 1721, is no amateur historian’s quirk: it is a declaration of epochal intent.

Meanwhile, on the ground, indications of an imminent summer offensive in the Donbas are multiplying. After the partial failure in Pokrovsk, the Russians have moved north, gaining useful ground to encircle Kramatorsk. The most favourable season for military operations has begun, and Russia wants to use it to consolidate its positions before any negotiated truce.

In this scenario, the only tangible result of the negotiations was an exchange of prisoners: one thousand on each side. An important gesture from a humanitarian point of view, but irrelevant on a strategic level. The war continues. And it does so with rhetoric that fuels, rather than extinguishes, the conflict.

The Ukraine case highlights the first cracks in the Trump Doctrine. Having built a negotiating framework based onspectacular unilateralism, Trump now finds himself trapped in his own promises. The threat to ‘back down’ is at bottom a communicative surrender: he cannot deliver what he sold to the voters.

Trump wanted to centralise all negotiations on himself, excluding the EU, marginalising Kiev and treating Putin as an equal interlocutor. But this strategy has structural limits: when the negotiation does not result in a media outcome useful to his narrative, it loses appeal.

The entire American posture in the Ukraine crisis is becoming a performance without a script. Trump’s performative diplomacy, which works on the campaign trail or in bilateral negotiation contexts (such as with Mexico or Canada), breaks down against theasymmetry of war.

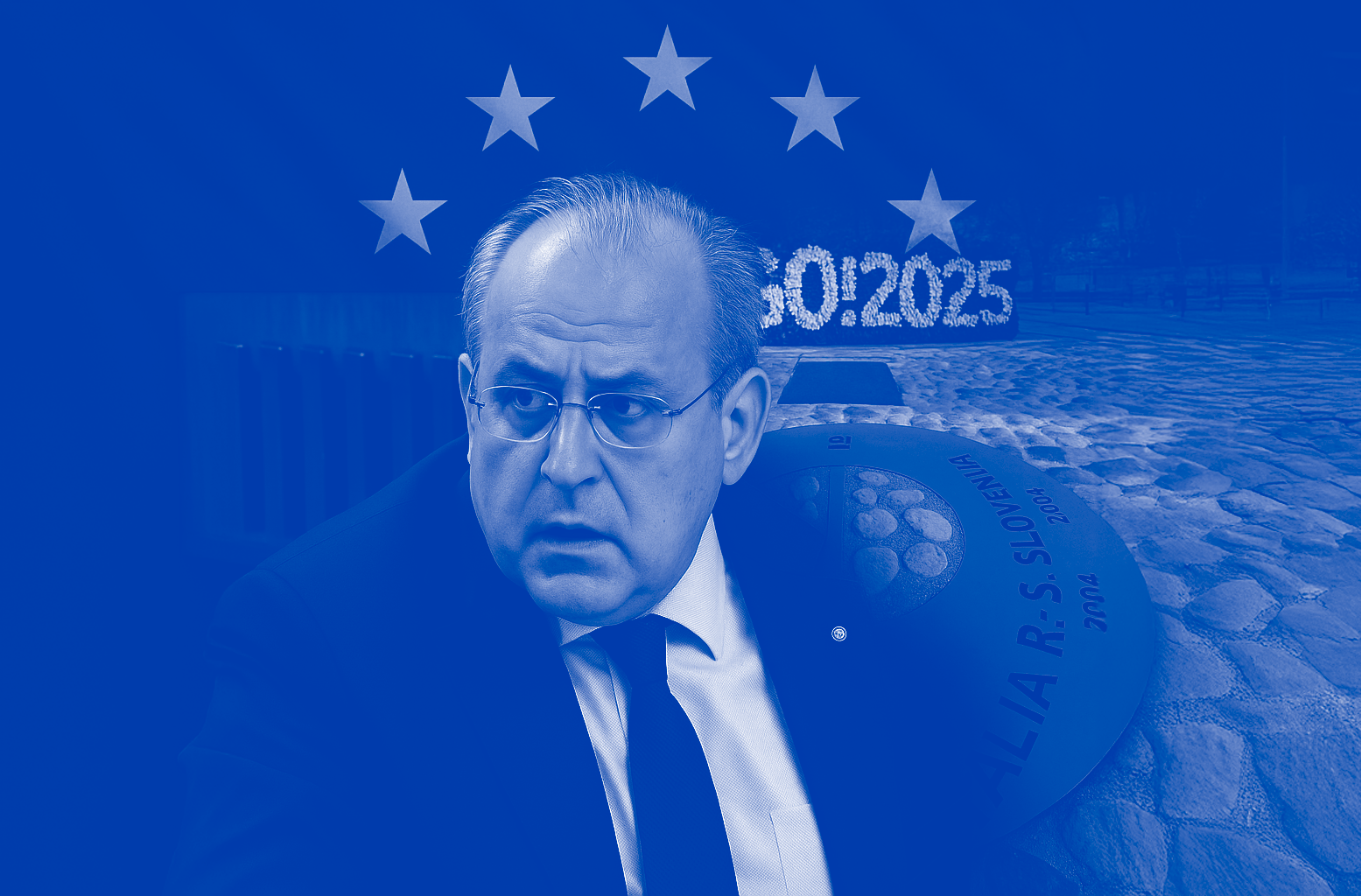

Europe, meanwhile, has remained an impotent spectator. The exclusion from the tables, the announced tariffs and the lack of a common strategy have highlighted the continent’s systemic subalternity. Trump is not looking for allies. He seeks extras in his own geopolitical theatre.

And yet, precisely at this difficult time, the White House does not seem ready to revise its approach. The idea of entrusting mediation to the Vatican, of not imposing new sanctions, of not directly involving the European institutions, are all signs of a distorted perception of communicative effectiveness.

Performative diplomacy is not real diplomacy

The Ukrainian affair, read through the Trumpian prism, highlights a deep fracture between two models of diplomacy management: on the one hand, structured, multilateral diplomacy, often slow but based on shared codes and institutional practices; on the other, performative or ‘spectacle’ diplomacy, centred on the symbolic gesture, the spectacular declaration, the narrative frame to be delivered to the media. Trump embodies the latter in a radical way. But its effectiveness is beginning to show deep cracks.

Since the beginning of his second term, Trump has chosen to treat foreign policy as an extension of his public persona: the charismatic negotiator, the global conflict resolver, the ‘strong man’ who, with one phone call, can upset the geopolitical balance. It is a vision consistent with his style, but ill-suited to scenarios of war attrition, where the symbolic dimension is rapidly eroded by the continuation of the real conflict.

At the heart of Trumpian performative diplomacy is an almost choreographic conception of foreign policy: every gesture, every phone call, every public announcement is designed to maximise the effect on perception, not necessarily on the concrete outcome. Trump has never made a secret of this approach. He had already theorised about it in his 1987 book-manifesto, The Art of the Deal, where he declared that ‘perception is often more important than reality’ and that ‘exaggeration’ is a legitimate tool for shifting the terms of a negotiation.

But between the business manual and international crisis management there is a profound distance. As much as the narrative of the negotiation-savvy leader may work in the management of a real estate deal or a hostile takeover bid, when applied to a large-scale war – with tens of thousands of casualties, territorial encroachment and a latent nuclear standoff – it runs up against the limits of its own rhetoric. Trump’s problem is not only that he promises impossible solutions, but that he constructs entire diplomatic strategies as if they were television sequences.

The idea that it is enough to ‘lock oneself in a room with Putin and Zelensky’ to find agreement – as repeatedly stated – is more consistent with the imagery of The Apprentice than that of a multilateral summit. In this sense, the current crisis is also a crisis of ‘deal-making as diplomacy’, because the international context does not respond to the logic of personal branding. And because, in front of a leader like Putin, Trumpian theatrics do not produce intimidation, but indifference.

The case of Ukraine proves this. The promise of peace in twenty-four hours – repeated at least 53 times during the election campaign – was functional in building a political myth. But the moment Trump is confronted with the reality of the facts, that promise turns into a communicative boomerang. The tone changes: from assertive to conditional, from certain to hypothetical. ‘I will back out,’ he said, expressing an unexpected negotiating fragility. It is a relevant rhetorical leap, because it signals that the president is no longer in control of the plot, but is its narrative hostage.

Performative diplomacy, to work, needs winning performances. But when the adversary – in this case Putin – does not participate in the script and instead disintegrates it with every threatening statement or every kilometre gained in the field, the whole set-up risks collapse. And with it, the international credibility of the United States as the director of negotiations.

The two-hour phone call between Trump and Putin was the perfect example of this crisis. Two hours of strategic nothingness, but full of symbols: the promise of the Vatican as a neutral venue, the withdrawal of the ceasefire proposal, the Russian concession to negotiate ‘without pressure’. But there is no substance behind these moves: only the illusion that the staging of peace can replace peace itself. Royal diplomacy, meanwhile, is languishing: France, Germany, the UK and Poland, who had supported the Jeddah initiative, have been downgraded to extras.

And then there is thestructural absence of the European Union, an issue that the Trump doctrine treats with stubborn indifference. Excluding Europe from the negotiating tables is not only a geopolitical choice, but a communicative one: it means recognising only ‘strong’ interlocutors, capable of offering quick and visible counterparts. But this approach risks leaving Trump alone when his natural allies – i.e. the Europeans – would be the first to support a credible peace based on a lasting balance. His ostentatious self-sufficiency is, in this sense, a sophisticated form of negotiating self-isolation.

The role of the economy as a lever of extortion

Another element of weakness is the selective use of economic leverage. Trump has made it clear that he does not intend to apply new sanctions on Russia, fearing an uncontrollable escalation. But the resulting signal, in terms of communication, is devastating: the American leadership appears reluctant, hesitant, ambiguous. The idea of ‘good business opportunities’ in the post-war period with Moscow, pronounced on live TV, has unhinged any remnants of deterrence. Where once there were red lines, today there are investment assumptions. And this, for Moscow, is an invitation to continue.

Ultimately, Trump’s performative diplomacy is faced with its fundamental paradox: it works as long as it can display victories, but becomes meaningless the moment it runs aground in contexts refractory to spectacle. The wars of attrition, the frozen negotiations, the opponents who do not play by the rules of staging – all this reveals the limits of an approach centred more on frame than on structure.

In his first term, Trump understood that grand gestures (such as meeting with Kim Jong-un or moving the embassy to Jerusalem) were enough to generate a winning narrative. But the second term requires coming to terms with permanent crises. And a permanent crisis, such as that in Ukraine, cannot be contained within the limits of a communication strategy based on the surprise effect. What is needed here is real diplomacy, made up of slow compromises, multilateral networks, widespread leadership.

But this, for Trump, is the language of others. He speaks in slogans, while history speaks in continuity.

The truth is that the Trump Doctrine has always been more fragile than it seemed. It works when it can control the timing and content. It collapses when confronted with the non-negotiable complexity of total war.

The contrast between Trumpian diplomacy and Russian strategy is measured by the distance between image and substance. Trump constructs communicative frames centred on his figure: he is the guarantor of negotiation, the promoter of peace, the manager of the scene. But every time reality knocks at the door – with missiles, troops, and ultimatums – the narrative cracks.

Putin, on the contrary, uses diplomacy as a theatre of war, not as an instrument to close it. Every negotiation is a test case for resistance to compromise. The logic is one of exhaustion, not mediation.

And Ukraine, caught between these two incompatible codes, risks being reduced to a pawn in a game played elsewhere. The American promise of a quick peace has shattered against Russian intransigence and geopolitical reality. Now an empty space remains – the one that Trump is threatening to abandon – and one that no one yet seems ready to fill.

Meanwhile, Europe is watching. Not without nervousness. And perhaps, for the first time in years, without the certainty of having a say.