Ambiguity makes Italy irrelevant

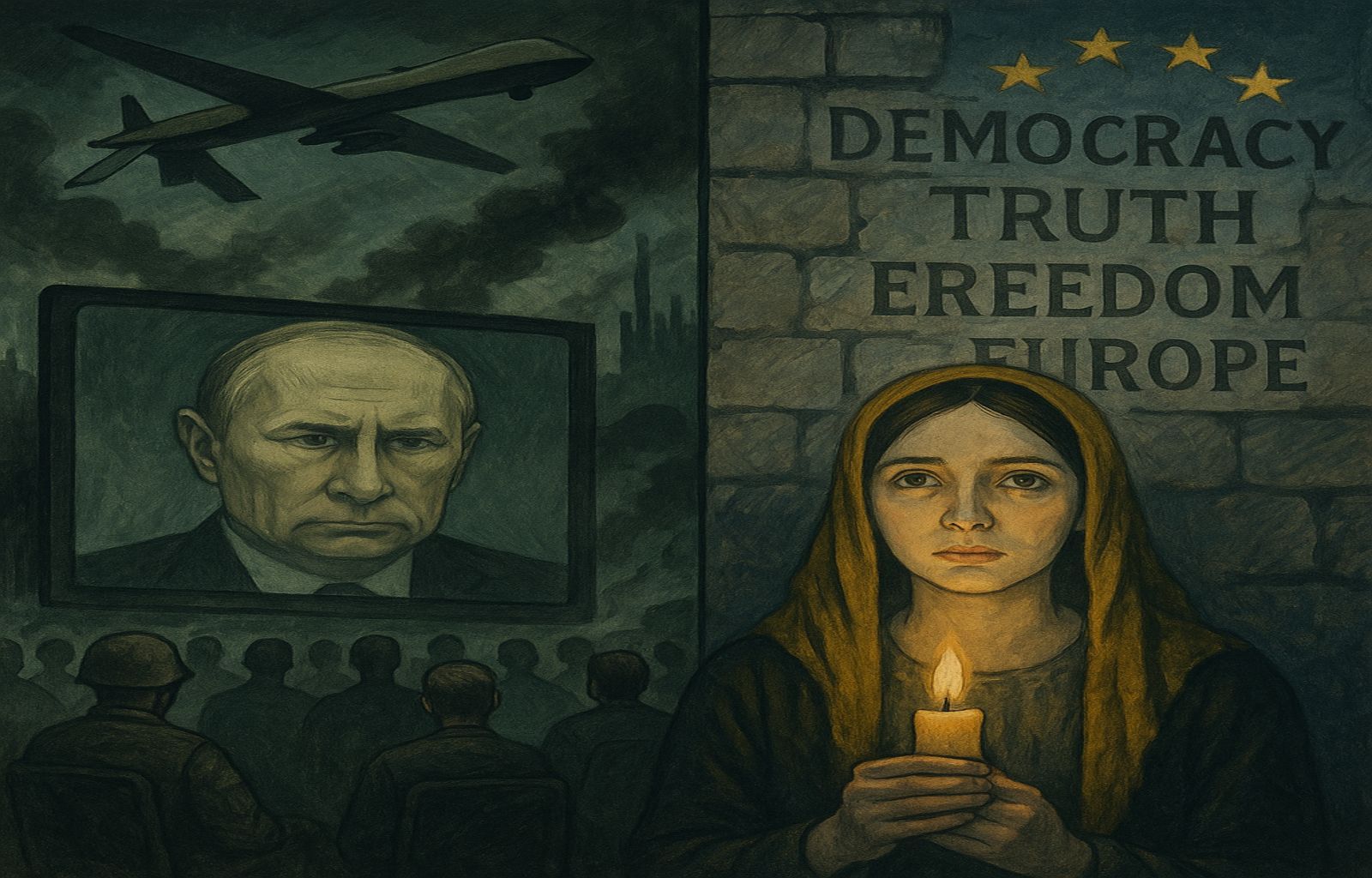

There is a time when not choosing becomes a choice in itself. And swaying Italy, today, seems to be walking with uncertain but steady step towards a marginal role in the great battle for the future of Europe and the West. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni ‘s absence from the ‘Coalition of the Willing’ summit, convened by Macron and Starmer with Zelensky in attendance, is not a minor detail. It is the plastic manifestation of an ambiguous strategy, which aims to keep one foot in two shoes: with Ukraine and with those who, after all, work against Ukraine.

Meloni chose not to be there. She said Italy was not willing to send troops – as if that summit was a call to arms, when in fact it was a reaffirmation of a political, symbolic and strategic commitment to the defence of the European order. Macron denied it with a mocking smile: ‘Too bad, there was no talk of troops‘. But Meloni, perhaps, knew very well what was being talked about. The problem is not Tirana. The problem is Rome.

Because the truth is that what is holding Italy back is not just an international calculation, but internal blackmail. The premier knows that the balance of the majority rests on a fragile axis. “Surely Meloni has wondered whether joining the coalition of London and Paris would jeopardise her relationship with Salvini,” writes Corriere della Sera. Translated: the League, which has always been ambiguous in its relations with Moscow, could have brought down the government. So Meloni chose to save the government, not honour.

But can one really govern Italy – and count in Europe – under the implicit blackmail of an ally that plays a different geopolitical game and is hostile to the interests of the free West? That seeks backing in Putin circles and sovereignist hawks? That openly opposes sending military aid to Kyiv and flirts with the idea of a weak, divided, frightened Europe?

It is not just a question of international relations. It is a question of consistency, of credibility, of vision. Because you cannot say you are for Ukraine and then receive in Rome, with all honours, a character like George Simion: a Romanian extremist with a pro-Russian background and anti-European positions, exhibited as a natural ally in the election campaign. And you can’t claim a pro-European line and then abstain in Strasbourg on fundamental European defence documents, as Fratelli d’Italia did while Forza Italia voted in favour and the Lega was parading.

This is not balance, but confusion and ambiguity turned into political practice: a line that satisfies internal tacticalisms and mortifies the country’s strategic position. The result is that the most solid European partners – Paris, Berlin, London, Warsaw and the Baltic countries – begin to look at Italy with distrust. As an uncertain, opaque, unreliable ally.

The opposition contributes to this race to the bottom, unfortunately. The 5 Star Movement, which has flirted with cheap pacifism and the most tired anti-Americanism, now opposes European rearmament and military solidarity, as if good hearts were enough to stop Russian missiles. In the European Parliament, the M5S and Lega vote almost always in line on foreign policy issues: two parties that, although on theoretically opposite sides, speak the same language of strategic ambiguity.

The time has come to break this spell and say clearly which side Italy is on. A country that makes itself small for fear of arguing with Salvini is a country that has already lost. Ambiguity, in foreign policy as in love, never lasts long. Sooner or later, everyone realises who you really are. And they leave you alone.